|

Challenge of the Big Trees

|

|

|

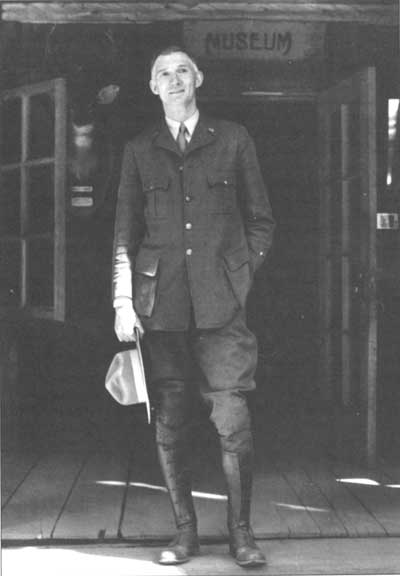

Chapter Six: Colonel John White and Preservation in Sequoia National Park (1931-1947) IN FEBRUARY 1936, Colonel John White delivered an address to a group of national park superintendents meeting in Washington, D.C. With nearly seventeen years at Sequoia National Park, White was one of the senior spokesmen, a man with experience ranging from the early days of Stephen Mather through to the Depression and its drastic government changes. He had seen park visitation multiply sixfold and auto use twelvefold. And he had seen it all from the perspective of his home park—Sequoia. With the benefit of those years of experience had come changes in the superintendent's philosophy and interpretation of the Park Service's 1916 charter—to use and preserve national parks. In his address, Colonel White expounded on that philosophy derived from his years in Sequoia:

Preservation, thus, was the paramount value according to White, not simple protection of objects as curious and isolated treasures, but protection and preservation of a nearly intangible feeling of national park "atmosphere." This represents one of the earliest expressions of systemic preservation, although admittedly immature and unscientific. What White wanted to protect was a semblance of the natural world, not some isolated objects within a much paved and adorned visitor complex. He still wanted heavy visitor use, but for education and enrichment. He still encouraged or accepted many types of use incompatible with today's Park Service values, but discouraged many others of common acceptance in his time. He believed that encouragement of the proper "atmosphere" in national parks had to be the province of the superintendent, as did the power to control and implement whatever policies and actions were necessary toward that end. White had developed these ideas by the late 1920s and simply refined and strengthened them as time passed. The situation at Giant Forest, where 80 percent of the visitors and seemingly even more of the problems concentrated, had forged in him strong likes and dislikes about Park Service policies and practices. The 1931 pillow limit applied to the concession in Giant Forest represented a partial victory in his ongoing war to make Sequoia fit the image later described in his address to the superintendents. However, White would face constant battles to protect and restore his ideas of national park atmosphere in Sequoia. In some areas serious pressure arose for the first time, such as the designs of road builders upon the backcountry. In other cases constant agitation for new development demanded unceasing vigilance and diplomacy particularly concerning popular amusements of dubious propriety. And in one area, Giant Forest, development clearly had already gone too far. The problem there would bedevil the Park Service throughout the system and throughout its history—how to remove facilities and suspend activities that had already become established. Having achieved the questionable adjective, "traditional," almost no practice with any adherents, no matter how offensive to administrators, could easily be halted. Thus in 1931 Colonel White faced an increasingly complex task; to control escalating development and, in fact, reduce it in some areas. For the next seventeen years Colonel White, his staff at Sequoia, and the Park Service itself would dramatically reassess priorities and policies. No longer was it imperative to scramble for visitors to justify a park's existence. The early generation of development minded Park Service officials like Horace Albright and Arno Cammerer gave way to a second generation. Colonel White's spirit and philosophy of atmosphere preservation replaced that of object preservation first at Sequoia and later nationally. In the process, the foundations of scientific inquiry and ecological preservation were laid as well. At Sequoia, White's experience, seniority, and personality would create a unique situation whereby policy initiation and impetus for change came from the local administration. This marked the only time in the park's post-1916 history when the Washington office was reduced to the role of policy reviewer rather than policy originator. Nevertheless, despite the shift of initiative, Washington always maintained ultimate veto and this would eventually bring an end to Colonel White's reign and a retreat from many of the standards he pursued and the difficult changes he demanded.

|

|

| ||

| <<< PREVIOUS | CONTENTS | NEXT >>> |

|

| ||

Challenge of the Big Trees ©1990, Sequoia Natural History Association dilsaver-tweed/chap6.htm — 12-Jul-2004 | ||