.gif)

Recreational Resources of the Alaska Highway and Other Roads in Alaska

MENU

Provisions for Recreational Use

A Plan for Recreational Facilities

|

Recreational Resources of the Alaska Highway and Other Roads in Alaska

|

|

Chapter IIII:

MAJOR ROADS OF ALASKA

In the past, Alaska's roads have been mainly disjointed, relatively short stubs, branching out from such population centers as Anchorage, Fairbanks, and Nome. Many have been "winter roads", tracks through the forest, sustaining travel by automobile only when boggy sections through which they pass have been frozen sufficiently to prevent miring down. Of prewar roads, only the Valdez-Fairbanks connection, the Richardson Highway, can be classed as of truly inter-city character.

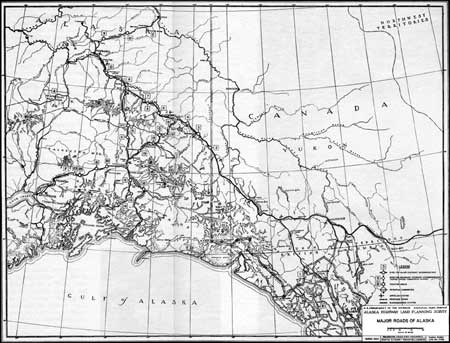

One requirement of the Nation's war program has been for highway access to points in Alaska not hitherto reached by that means. With this has come an expansion of facilities of this nature which gives the Territory a first nucleus of coordinated roads, joining major cities with each other and the cities of Canada and the United States. The way in which this has been accomplished can be seen from figure 22, facing the following page.

|

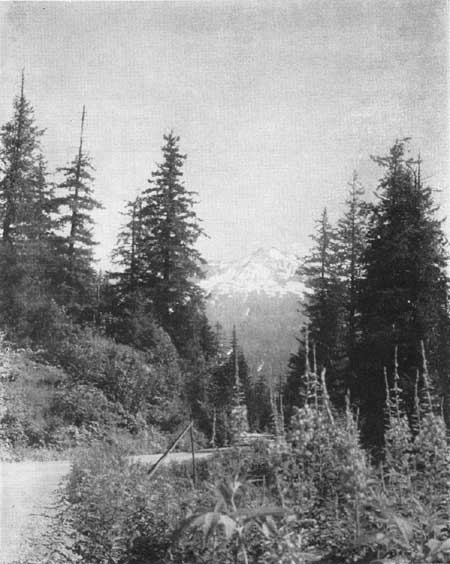

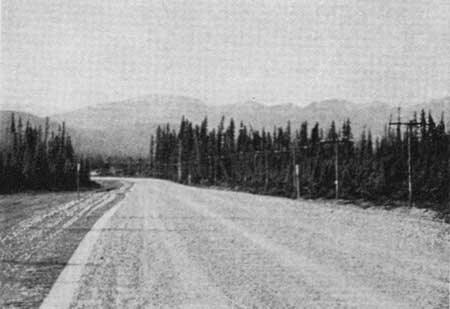

| Figure 20.—North from the sea by Richardson Highway. |

THE ALASKA HIGHWAY. Undertaken as a requirement of military security, and under the stress of apparent urgency, the Alaska Highway may eventually prove of even greater economic than military significance. Alaska has been the goal of thousands of tourists; completion of this first road link with Canada and the States may increase greatly the number of these potential friends of the Territory.

Unlike the Richardson and some of the other roads in Alaska, this highway has not developed through continued improvement of early trails; for the most part it has been cut through untracked wilderness during the seasons of 1942 and 1943.

The total length of the Alaska Highway, including spur and terminal branches, is about 1,660 miles, of which 1,338 are in Canada. Road distances from Dawson Creek to some of the terminal Alaskan cities are as follows:

| Anchorage—1,647 miles | Haines—l,175 miles |

| Fairbanks—l,532 miles | Valdez—1,586 miles |

History.Construction of a highway connecting Alaska with the States is not a new thought. For years, many of those most interested in the welfare and growth of the Territory have realized and urged the advisability of such a project, have studied possible routes, and have sought means of effecting the desired result

As early as April, 1931, pursuant to an Act by the 1929 Territorial Legislature, the Alaska Road Commission prepared and published a report entitled "The Proposed Pacific Yukon Highway." By specific authority of the Congress, the President designated three special Commissioners in 1930 "to cooperate with representatives of the Dominion of Canada in a study regarding the construction of a highway to connect the northwestern part of the United States with British Columbia, Yukon Territory, and Alaska". The report of the United States Commissioners, to the President, was dated May 1, 1933, but specific action was lost in the economic depression which was then prevalent.

On August 16, 1938, again by specific authority of the Congress, the President appointed a five-member Alaskan International Highway Commission for the purpose of making a similar study. Its report, dated April 20, 1940, was received by the Congress, referred to the Committee on Foreign Affairs, and printed as House Document No. 711 of the 76th Congress, 3rd Session.

One essential difference is apparent between the routes discussed in these reports and the one upon which the Alaska Highway is now built. Previous proposals contemplated the utilization of existing Canadian roads from Seattle and Spokane to Prince George or Hazelton, thereafter following the so-called "Rocky Mountain Trench" lying between the Pacific Coast Range and the Rocky Mountains. The Alaska Highway stems from midwestern rather than western states, and its southern portion lies east of the Rocky Mountains.

Basic to the selection of this location is the logic which finally determined construction of the road. Air transport had come of age, whether for civilian or military purposes. The great-circle course from the North American center of population to the Orient lies generally along the route which the Highway follows. The Allied Nations were faced with threatened Japanese invasion of Canadian and United States territory by way of Alaska. Long range plans for offensive thrusts toward the Orient indicated the necessity for availability of speedy movement of personnel and war materiel to Alaskan points. The time-honored method of steamer travel was too slow for dependence in crises, vulnerable to hostile naval actions as well. The air was the answer. The Rockies interposed a defensive screen from less favorable flying weather over the Pacific coast, and from possible coastal attack. Canada established a series of small airports along the direct, great-circle course, later to be enlarged and improved by the United States. Regardless of its function in times of peace, the Alaska Highway has been planned and built primarily to facilitate the development of these fields and their operation for military purposes.

Dawson Creek became the southern terminus of the Highway, not because of road connections from the southeast, which are anything but favorable, but because it is the present "end of steel" from that direction, a railhead and a base for operations. Similar bases were established at other railheads, at Whitehorse on the White Pass and Yukon, and at Fairbanks on the Alaska Railroad.

At first, it was planned for engineer troops to thrust a pioneer road through the wilderness, and for a group of civilian contractors under direction of the Public Roads Administration to follow with construction of a standard highway, using the Army pioneer road for access. Plans were later modified so that, in many places, work of the contractors was improvement of the pioneer location rather than construction of an entire new road. By this means a reasonable compromise was achieved between speed of completion and standards of construction.

|

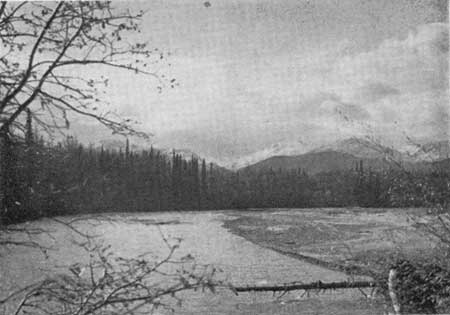

| Figure 21.—Section of pioneer alignment retained, Alaska Highway. |

Acclaim has been accorded, and rightfully, to the pertinacity and resourcefulness which accomplished completion of the pioneer road in 1942, to willing endurance of physical hardships and to victory over difficulties in connection with services of supply. Progress during 1943 was less spectacular but no less effective. During that summer the character of the road changed from that of a passable trail to that of a gravel road of high standards, with permanent bridges and drainage structures, adequate for tourist or commercial traffic, if maintained in accordance with usual practice.

|

| Figure 22.—Main Roads of Alaska. (click on image for a PDF version) |

The Route and its Recreational Resources. Road approach from the States to Dawson Creek is long and onerous. The population center of the nation at the time of the 1940 census was about 36 miles south of Terre Haute, Ind. The shortest main highway distance from there to Dawson Creek, by way of Edmonton, is 2,676 miles, and to Fairbanks 4,208 miles. The drive across the level prairie land of North Dakota and southern Saskatchewan is not at all inspiring and will be regarded by most tourists as a necessary chore before enjoyment of the trip can really begin. In general, before reaching the Alaska Highway, road standards decrease as distance from concentrations of population increases. The highway system of western Canada, because of the ratio between mileage and persons served, does not yet afford ease of travel common in the States. In 1940, the Province of Alberta maintained a total of more than 92,000 miles of road; a typical mile would have been paved 4 feet, bituminous-surfaced 35 feet, graveled 172 feet, and plain earth for 5,069 feet. The meandering route from Edmonton to Dawson Creek is of such low standard that it will discourage many potential visitors to Alaska from going farther afield. Until it has been improved, full benefits from recreational travel will not be realized from the Alaska Highway.

Terms of the agreement between the United States and Canada covering construction of those parts of the Highway which lie within the Dominion provide that Canada shall furnish the necessary rights of way and that the United States shall construct the Highway and maintain it "until the termination of the present war and for six months thereafter unless the Government of Canada prefers to assume responsibility at an earlier date of so much of it as lies in Canada". They further provide that at the war's end "that part of the highway which lies in Canada shall become in all respects a part of the Canadian highway system, subject to an understanding that there shall at no time be imposed any discriminatory conditions in relation to the use of the road as between Canadian and United States civilian traffic". There appears no stipulation of degree of maintenance by either government.

From Dawson Creek the Alaska Highway follows an old Provincial road 50 miles to Fort St. John, crossing on the way one of Canada's largest rivers, the Peace. From Fort St. John to a short stub road connecting with the Fort Nelson airport the route is through a rolling, wooded terrain, much of the way along the ridges, in order to avoid, so far as possible, the muskeg country to the east.

Fifty miles west of Fort Nelson the road enters the foothills of the Rocky Mountains, and follows the Tetsa River to Summit Lake (elevation 4,212), the highest point on the Alaska Highway. Muncho Lake, 70 miles beyond the divide, is one of the beauty spots of the Canadian journey. Dropping down to the Liard River, another great northern stream, the Highway emerges from the mountains, crosses the Liard, and follows its northerly bank to Watson Lake, which lies just inside the southern limits of the Yukon Territory. Here again, a stub road leads to a major airport.

|

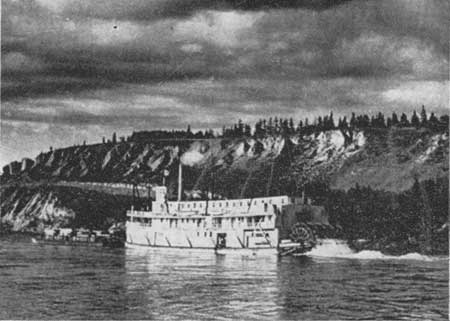

| Figure 23.—Yukon River steamer leaving Whitehorse. |

Progress is generally westward from Watson Lake, without great deviation from the British Columbia-Yukon boundary as far as Teslin Lake, crossing from MacKenzie to Yukon drainage and encountering much swampy terrain. Skirting the northeast shore of Teslin Lake, the highway crosses its outlet river, and swinging southwest to Marsh Lake, follows the Lewes River to Whitehorse, with a detour possible by way of Carcross, a community on Lake Bennett, of considerable importance in the days of '98 and even now connected by summer steamer with Atlin, mining center of northern British Columbia.

Whitehorse is the only community of consequence from beginning to end of the Alaska Highway, and here the tourist will do well to break his trip and tarry awhile in contemplation of the changes which the years have wrought.

The Bonanza strike of 1897, near Dawson, brought between 30,000 and 50,000 persons to the Klondike within a year. Many of these passed through what is now Whitehorse, choosing the hazardous trails from Skagway by way of Chilkoot Pass or White Pass. Reaching Lake Bennett, the gold seekers provided themselves with boats for the journey by water to Dawson. The most dangerous part of the trip was at Miles Canyon, through which the Lewes River rushes in a series of rapids, called Whitehorse because of a fancied resemblance of wave-foam to flying manes. At the foot of the rapids boats were bailed out and gear spread to dry. Here on the east bank the old town of Whitehorse sprang up, across the river from the present site. Jack London was one of those who piloted inexperienced boatmen through the rapids, and Robert Service worked as a clerk in Whitehorse and in Dawson. Rex Beach and Joaquin Miller were other writers who experienced the thrills of the Klondike.

In 1940, Whitehorse was a sleepy reminder of the boom-days town of 1898. With a population of about half a thousand, it was primarily important as the terminus of the White Pass and Yukon Ry., a transfer point from railroad to river steamer, as a supply center for the people of the surrounding country, and as an outfitting point for expeditions of miners and hunters.

|

| Figure 24.—Haines Cutoff—only road link to Southeastern Alaska. |

When construction of the Alaska Highway began, Whitehorse once more became a jam-packed center of hectic bustle and frenzied industry. Headquarters of the Northwest Service Command, established by the Army to handle the Highway, it teemed with the activities of that agency. It is a key location in the much-mooted petroleum recovery system whereby crude oil is pumped from the Norman Wells field to new refineries at Whitehorse, whence the products are distributed by pipe line in both directions for the entire length of the Highway and to tidewater at Skagway. Although the end of the war will bring lessening of congestion at Whitehorse, some of the operations there begun will no doubt continue under peacetime conditions.

Westward from Whitehorse the Highway follows the general alignment of old trails in the valleys of the Takhini and Dezadeash Rivers to Kluane Lake. At Champagne, a settlement at the junction of these trails with a former one through Chilkat Pass from the south, atop a knoll beside the road, is an old burying ground in which the Indian graves are covered by miniature houses, complete in detail of windows and curtains, according to tribal custom.

A hundred miles west of Whitehorse the Highway is joined by the present day version of the old trail through Chilkat Pass, the Haines Military Road or Cutoff, integral and important part of the Alaska Highway. This road, 159 miles long, follows for 42 miles a road built earlier by the Alaska Road Commission from the port of Haines to the Canadian border. The next 50 miles are in British Columbia, passing through singularly beautiful Chilkat and Three Guardsmen Passes. The last part of the way lies within the Yukon Territory, skirting Dezadeash and Kathleen Lakes, and joining with the through route of the Alaska Highway to form the northeast boundary of a tract of some 10,000 square miles which has been reserved by the Dominion Government so that it may be available, in present condition, for establishment as a national park.

About 136 miles west of Whitehorse the Alaska Highway reaches Kluane Lake and then follows its southwestern shore for about 40 miles to Burwash Landing. Kluane ranks with Muncho Lake in scenic aspect, but the pioneer road, climbing to a vantage point at Soldier's Summit, offered more spectacular vistas than does the present easier gradient along the water edge. Kluane at the southern end, and Burwash Landing near the northerly limits of the lake, are long-established trading posts. Before the relative ease of access brought by the Highway, Burwash Landing was expeditionary headquarters for many a party of wealthy big-game hunters. The Highway will affect this activity considerably.

From Kluane Lake the Highway takes to the foot-hills, bridges the Duke and Donjek Rivers and comes to a high-level canyon crossing of the White River. Downstream is displayed an instance of "braiding" which is to become so familiar later in the glacial streams of Alaska. This section is characterized by views of the St. Elias Mountains to the south, particularly up the valleys from stream crossings.

From the White River to the Alaska boundary, at the 141st meridian of west longitude and 307 miles from Whitehorse, the trend is more to the north, through low hills, across many streams, and past numerous lakes, smaller than Kluane but interesting as the panorama unfolds. The Highway crosses the border in a swampy valley. North and south stretch narrow slots, cleared through the wilderness to define the boundary between two great Territories.

|

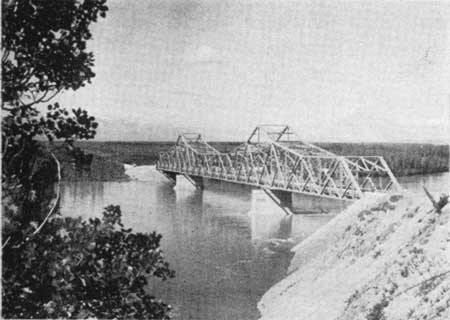

| Figure 25.—The Highway bridges the Tanana. |

Five miles beyond the border the road climbs from the swamp, and thereafter follows the north side of the Tanana Valley. At first the highway dips and swirls amid the light-green summer foliage of birch and aspen, through pleasant rolling terrain; later the enclosing hills incline more steeply toward the valley floor, and from the way along the slope more frequent vistas to the south are opened through the now prevailing spruce. The level foreground is strewn with lakes of varying size, and near at hand the snaky trace of the Chisana accompanies the course of the Highway. Enclosing the valley on the south are the Nutzotin Mountains, and beyond these are revealed the higher summits of the Wrangells.

Forty-three miles from the border a short branch road crosses the Chisana and leads to the Northway airport, 6 miles south among the lakes. Five miles beyond this point the Highway overlooks the Chisana and Nabesna Rivers, glacier-born but now calm, as they unite to form the Tanana.

As the Highway proceeds the prospect is without decided change. The northwestward march of the Nutzotin Mountains is continued by the Mentastas. Tanana's course is not less tortuous than that of tributary Chisana; occasional ox-bows and back water channels attest the constant struggle to achieve its final bed. Valley lakes are more evident than ever; for more than a mile the Highway follows the shore of Midway Lake, which, over 3 miles long, is said not to exceed 8 feet in depth.

Swooping across the Tanana 83 miles beyond the Yukon line, the Alaska Highway forsakes the hills and fleets arrow-straight for 11 miles across the level valley floor to Tok Junction, bridging the Tok River about midway. This is a relocation of the preliminary route, which followed the hills north of the Tanana, crossed the river downstream from its juncture with the Tok, and thus avoided bridging the lesser stream. At Tok Junction, now only a meeting place of roads in the surrounding monotony of level and uniform spruce growth, the Mentasta Road section of the Alaska Highway swings southward to connect with other highways leading to Valdez and Anchorage.

|

| Figure 26.—Nearing Cathedral Rapids. Alaska Highway. |

Twelve miles from Tok Junction, pursuing the tangent course toward Fairbanks, the Alaska Highway is crossed by a short diagonal road. To the left is a radio beam station, to the right the Tanacross airport, separated by the Tanana River from the Indian village known as Tanana Crossing.

Five miles beyond, the Highway leaves the valley floor and again resumes its rolling way, this time along the lower slopes south of the Tanana. The valley narrows, and the hills at Cathedral Rapids confine the route. Beyond this brief constriction the road rides a series of plateaus which are some what elevated above the river, dipping slightly to cross the main streams as they are encountered, the Robertson, Johnson, Little Gerstle, and Gerstle.

Alignment is now easier, with sweeping curves and longer tangents than prevail east of the Tanana. About 75 miles from Tok Junction, before reaching the Gerstle, begins a tangent which continues, with slight deviations, the remaining 33 miles to the technical end of the Alaska Highway, its junction with the Richardson, about 10 miles south of the point where that highway crosses the Tanana River.

This section is scenically mediocre, resembling that from the Tanana River bridge to Tanacross. Alignment and profile are monotonously straight, and the way is hedged by solid spruce growth, of little interest to the traveler. Occasionally the tedium is enlivened, at stream crossings, by views northward across the broadened valley or southward to the Alaska Range. Perhaps development of this section for agriculture, to which it seems suited, will open vistas and add interest to the scene.

|

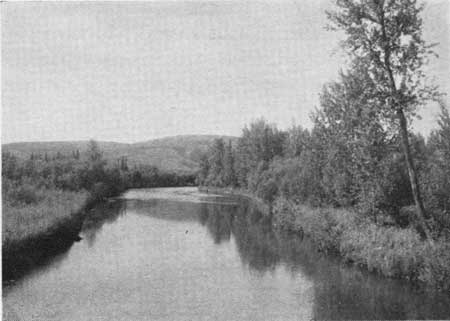

| Figure 27.—The Tok River. |

Return now to Tok Junction and the Mentasta Road southward along the general route of the old Eagle trail of Captain Abercrombie's day. The way lies straight and level for 8 miles across the broad confluence of Tok and Tanana Valleys. Thereafter, twisting and turning, the road climbs the narrowed valley of the Tok, first on the west bank and later on the east, until the river swings sharply away to the west, whereat the route abandons it and veers up the valley of the tributary Little Tok as far as Mineral Lake, about 34 miles from the start at the highway junction. Swinging westward along Mentasta Creek and through Mentasta Pass, the road rounds beautiful Mentasta Lake, crosses the Slana River, and drops down its westerly bank to the almost deserted settlement of Slana, where it joins the Abercrombie Trail. The distance covered from Tok Junction has been 72 miles; Slana is 64 miles from the Richardson by Abercrombie Trail.

Travelers for recreation will find Mentasta Road the most engrossing portion of the Alaska Highway. Its scenic environment is superior and the route interesting, more intimate in character than the Highway generally. In following one of the defiles through the Alaska Range, it mounts to an elevation higher than any traversed by road in the Tanana Valley. Near the pass, 50 miles from Tok Junction. Mentasta Lake offers pause in the hurried schedule, and invites dalliance by its mountain-mirroring waters. The lake is almost completely encircled by intermediate heights of the Alaska Range, yet these are at such distance that they appear in pleasing perspective, and not so close that only immediate foreground slopes are visible. The effect is of spaciousness and of extended views rather than of restriction. Mentasta is almost the only spot along the Alaska Highway which merits development of a recreational nature to provide for more than a casual overnight stop by the tourist.

Standards of alignment and construction have been somewhat lower for the Mentasta Road than for other Alaskan portions of the Highway. This may be due to the more rugged nature of terrain traversed, and perhaps also to the greater military significance of highway access from the east toward Fairbanks. The present road over Mentasta Pass is hazardous, with narrow shoulders, sharp curves and grades, and inadequate sight distances. In common with the Haines Cutoff, it must be made comparable with the through route to Fairbanks before maximum tourist use is possible.

|

| Figure 28.—Mentasta Road, in the valley of the Little Tok. |

Tourist Accommodations. There are no provisions for entertainment of travelers along the Alaska Highway within the Territory. The only communities within miles of the route are Native villages at Tetlin and Tanacross, and even these are separated from it by the Tanana. There has been no chance for establishment of commercial roadhouses because of the withdrawal from entry of lands adjacent to the Highway, nor will any establishment of this nature be possible until the withdrawal has been relaxed. During the periods of construction and military operation, accommodations for persons who were concerned with these functions were available at temporary roadside camps maintained by the Army and by civilian contractors.

RICHARDSON HIGHWAY. Earliest unit in the Alaskan system, this highway links the Gulf seaport of Valdez with Fairbanks, commercial and mining center of the great Interior. It is named for the first president of the Alaska Road Commission, General Wilds P. Richardson, in whose honor a tablet has been placed at Isabelle Pass, the highest point reached by the highway.

Captain Abercrombie's military explorations of 1899 resulted, two years later, in construction by the War Department of a pack trail from Valdez to Eagle, by way of Copper Center, Mentasta Pass, and what is now Tanacross. By 1904 a similar trail had been extended from this at Gulkana, by way of Isabelle Pass and the Big Delta and Tanana Rivers, to Fairbanks. By successive stages this direct route from Valdez to Fairbanks has been improved, and in 1927 it reached automobile standards. Principally because of heavy snow slides in the extreme south portion it has not been kept open to through winter use, although local traffic continues in some sections. Its total length is 371 miles.

From a scenic standpoint, two locations will be of particular tourist interest, the crossing of the Alaska Range between Big Delta and Gulkana, and the down-hill slide at the southern end from Thompson Pass (elevation 2,722) to Valdez, 25 miles away.

The drive from Fairbanks southeast to Big Delta is rather commonplace, save for occasional glimpses of the Tanana River and Salchaket and Birch Lakes, where vacation colonies serving Fairbanks have come into being. Proceeding south from Big Delta, the Alaska Range peaks of Hayes, Hess, and Deborah are seen across the Delta River, on the right. From Pillsbury Dome, near the highway, the panorama of Tanana Valley unfolds to the northward. Beyond Isabelle Pass (elevation 3,310), the highest point on the Richardson Highway, are Summit and Paxson Lakes, favorite fishing haunts. This is wild-game country, with bear, moose, and mountain sheep. From Gulkana to Copper Center impressive views of Mounts Sanford and Drum are obtained across the Copper River valley. Midway from Copper Center to Valde the scenery becomes more interesting and intimate, the road follows swift mountain streams and the monotonous regularity of relatively level spruce growth becomes varied. The long climb of 1,600 feet in 22 miles begins; tree growth dwindles and Worthington Glacier is openly visible, within a quarter-mile of the roadside.

|

| Figure 29.—Thompson Pass. |

Thompson Pass is rather bare of vegetation, the surfacing stones flattened by ancient glaciers. Here, atop the Chugach Range, begins the descent to Valdez. The road drops 2,000 feet and, following the Lowe River, offers Snowslide Gulch, where the bridge must be replaced annually, aptly-titled Bridal Veil and Horsetail Falls over 300 feet high, and Keystone Canyon. From its cliff-like sides the Lowe may be seen, far below. Relocation and tunnel construction, begun in 1944, will bring this short section of road almost to river level, improving the highway gradient and avoiding Snowslide Gulch, but depriving the sightseer of a measure of scenic splendor. The last ten miles of the way to the sea at Valdez are through lush tree growth, festooned with streamers of moss, characteristic enough of conditions along Alaska's southeasterly coast but strangely at variance with the country traversed on the trip from Fairbanks.

Accommodations for the recreational traveler along the Richardson are not adequate, and must be supplemented if visitors reach Alaska in expected numbers. There are no hotels or tourist camps as such are known in the States. Scattered along its 371 miles of length there have been as many as two dozen roadhouses, but the transition from pack horse to motor stage, coupled with diminution of private travel during the war period, has forced most of them to abandon operation. Some of them may be revived by a resurgence of business, others are in advanced stages of decay and irrecoverable. Perhaps no more than five or six in all would fit into the required program of travel facilities.

|

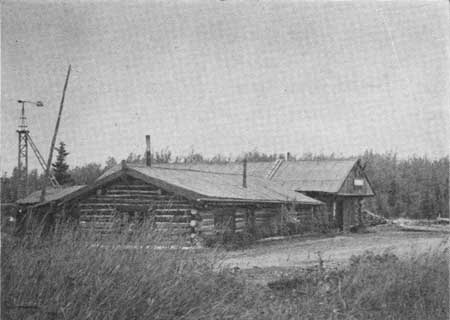

| Figure 30.—Sourdough roadhouse. |

The Alaska roadhouse is an institution which must be encountered familiarly to be appreciated. There the term does not connote in the least the type of use or misuse which has come to be associated with it in the States. Alaska roadhouses are functional necessities to travel through country populated sparsely or not at all. They are inns or taverns in the honest, Colonial sense, providing food and shelter for the traveler today as they did for his predecessor a generation ago, but now supplying oil and gasoline for the motor car instead of the hay and grain required by its equine forerunner. More, they often serve as trading posts for tributary populations, whether Native or white, sources of supply for pack trains, prospectors, and trappers, the first link in the chain of processes through which the raw pelt becomes milady's stole. They are post offices as well as general stores, often linking enough functions to become real communities in themselves.

The earlier roadhouses were apt to be sprawling, one-storied, log-buildings, with sod roofs perhaps strangely fitted together. Later came structures of two or even three stories, some of squared logs, others of frame construction, sometimes incongruous with their wilderness settings. In planning for the accommodation of recreational travelers, it would seem a fitting tribute to the part which these buildings have played in the development of Alaska, to adopt the better principles which they have exemplified, with such modern adaptations as would add to the comfort of the visitor without sacrificing atmosphere and precedent.

|

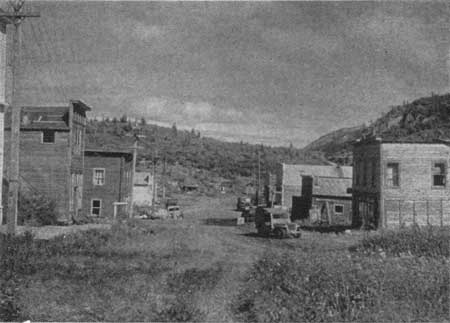

| Figure 31.—Chitina, Alaska—1944. |

EDGERTON CUTOFF. Named for Maj. Glen C. Edgerton, a former chief engineer of the Alaska Road Commission, this 39-mile stretch of road connects Chitina with the Richardson Highway at Willow Creek, about 92 miles north of Valdez. It was once an important link in transportation between the Interior and the coast, since Chitina was on the now defunct Copper River and Northwestern R. R., and a stagecoach was operated from Chitina to Fairbanks. Today, Chitina has rather the aspect of a ghost town.

Among recreational resources along the Edgerton are the northward views of the Wrangell Range, when the weather is clear. Mounts Blackburn, Wrangell, Sanford, and Drum dominate the panorama, ranging from 12,000 to 16,000 feet. A wayside picnic spot has been developed at Liberty Falls, 10 miles from Chitina. This also serves as a parking place for those who would photograph the falls or whip the fishing stream below. Nearing Chitina, the road drops down beside three beautiful lakes, climaxed by Lake Chenan, which abounds in grayling.

There will be two main purposes for recreational travel over the Edgerton Cutoff to reach Chitina; first, because of interest in the town and its aura of past history; and second, as a means of access to the big-game country to the eastward. Perhaps it is not too far-fetched to visualize, in the era of auto travel to Alaska, a revitalization of old Chitina as an outfitting center for hunting and fishing expeditions into the hinterland.

Although Chitina is only 39 miles from the main artery of the Richardson Highway, accommodations for the traveler are somewhat in keeping with its "ghost" status. If it regains some of its lost air of busy traffic, provisions for lodging and feeding transients will no doubt be augmented and improved. For the present, a non-urban overnight stop in the vicinity of the Chitina Lakes appears advisable.

|

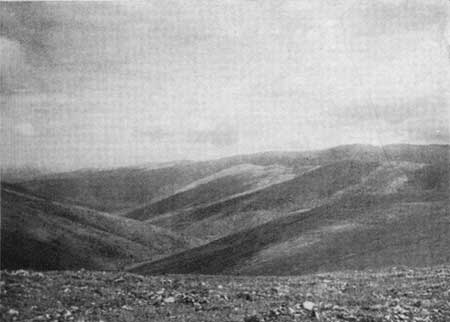

| Figure 32.—View from a summit on the Steese Highway. |

STEESE HIGHWAY. As president of the Alaska Road Commission from 1920 to 1927, Gen. James G. Steese rehabilitated the highway system of the Territory in the years following World War I. This included construction of the highway which now bears his name. Prolonging the Richardson Highway 162 miles northeasterly from Fairbanks to the Yukon River at Circle, it there reaches the most northerly point in the Alaskan road system. In addition, at Eagle Summit (elevation 3,880), it climbs to the highest point attained by any road in the Territory.

Although not originally built to standards of width, alignment, and foundation comparable with those in force on the Alaska Highway, the Steese has gradually been improved to a condition of easy travel. It passes through a scenically beautiful terrain and permits inspection, at close range, of some of Alaska's most important placer mining. Bones and tusks of prehistoric mammals and some artifacts of stone have been recovered from the section traversed by the Steese. Large herds of caribou sometimes cross it during their autumnal migration. The hunter should note that regions of favorite crossing are protected, and that shooting of caribou in the vicinity is prohibited. Fishing is reputed to be excellent in the streams which are paralleled and intersected by the Steese.

About 130 miles from Fairbanks a spur road leads southeast 9 miles to Circle Springs, a summer and winter resort developed around mineralized springs which flow 400 gallons a minute at a temperature of about 139°. Besides its therapeutic values, the water of the springs has been utilized to heat the hotel, cabins, and other buildings which comprise the resort. Summer communication with Fairbanks is accomplished by road, but at other seasons reliance must be upon air transport.

At the north end of the Steese Highway summertime connection is made with the river boats at Circle, a village of about 100 persons, mostly Natives. The derivation of its name has already been noted. Circle retains little of its earlier importance.

Factors tending to recreational use of the Steese are its scenic environment, desire of the tourist to achieve "farthest north by road," connection with the Yukon boat trips, and apparent incongruity of hot springs so near the Arctic Circle. Amount of use will probably not equal that of the Alaska, Richardson, or Glenn Highways.

As many as eight roadhouses, spaced approximately 20 miles apart, have been in operation at one time or another along the Steese Highway. Probably a third of this number will serve the seasonal use of such tourists as venture upon it.

|

| Figure 33.—Elliott Highway crosses the Chatanika River. |

ELLIOTT HIGHWAY. Branching from the Steese about 11 miles from Fairbanks, the Elliott Highway leads northwest about 75 miles to Livengood, a placer mining district. It appears that little use of the Elliott will be made by recreational travelers.

THE ABERCROMBIE TRAIL. Although comparatively new as a highway, the Abercrombie Trail follows, for at least half its length, a portion of the route from tidewater to the Klondike which was first explored in 1899 by Capt. William R. Abercrombie. Leaving the Richardson Highway about 3 miles north of Gulkana, the present day road follows the valley of the Copper River 64 miles northeasterly to Slana, as did the Eagle trail, but there swings southeast about 40 miles to Nabesna, tapping the mineralized area north of the Wrangell Mountains.

Chief importance of the Abercrombie Trail in the picture of recreational travel lies in utilization of its western half as a portion of the new direct route from the upper Tanana Valley to Anchorage. Views of the peaks of the Wrangell Range are rather impressive when weather conditions are favorable. A glance at the map (fig. 22) will reveal the way in which the northwestward thrust of the mountains is more than half encircled in the journey from Chitina to Nabesna. The section of the Abercrombie between Slana and Nabesna has been little used or maintained during war years because of curtailment of mining at its terminus. Postwar resumption of such operations and suitability of the region about Nabesna for vacation pursuits will perhaps act to increase the importance of that part of the road.

Following the precedent of earlier highways, roadhouses have been established near crossings of the Gakona, Chistochina, Indian, and Slana Rivers. During the period of war activity some have lapsed into the status of road maintenance camps; others have been operated largely for the convenience of freight truckers handling government shipments of materiel, supplies, and equipment, for use on the Alaska Highway. Some of them may be adapted to tourist use after the war, but additional sites will require to be developed.

GLENN HIGHWAY. Constructed as a war necessity and contemporaneously with the Alaska Highway, although by the Alaska Road Commission instead of the Army, the Glenn Highway is of equal importance in the Alaskan road system with its more widely heralded companion piece.

Before the war, Anchorage was connected by road with the agricultural colony in the Matanuska Valley, a 50-mile stretch of road running northward from the Westward metropolis to Palmer. The Glenn picks up at Palmer and, following east along the northerly valley sides of the Matanuska and Tazlina Rivers, joins the Richardson Highway at a point midway between Copper Center and Gulkana, 115 miles north of Valdez. The new intersection, near the settlement of Glennallen, is 256 miles distant from Fairbanks and 242 miles from Anchorage.

Interflow of road traffic is now possible between Anchorage, Valdez, Fairbanks, Circle, Chitina, and all intermediate locations on the highway network connecting them. The effect of this construction upon the economy of Alaska will be considerable. It may well be assumed that some items of steamer freight from the States, previously carried from Seward to Fairbanks by railroad, will henceforth be trucked to parts of the Interior from Anchorage. Movement of freight over the Richardson Highway out of Valdez has been restricted by the long, steep climb at the start, and by necessary closing during the winter months. Such disadvantages are not evidenced in the case of the Glenn.

The postwar tourist will probably enjoy his trip over the Glenn more than that over any comparable section of Alaska road. The monotony of scenery sometimes apparent elsewhere is not evident here. Fifty miles away from Anchorage he is in the heart of the Matanuska community, now in full, efficient, and remunerative operation. East of Palmer the terrain grows more rugged; the view to the north upstream along the Chickaloon River is intriguing to passing fancy; southward across the Matanuska unfold the Chugach Mountains; from them roll the glaciers, Matanuska, Nelchina, and Tazlina. Nearer Glennallen a quieter tempo is resumed; the road straightens, speeding to its rendezvous with the Richardson. Yet the relatively direct route is not wearying, for in the far distance, set as a target or range beacon beyond Glennallen, rear the snow-tipped masses of Mounts Drum and Sanford.

Because it has been so newly opened, roadside accommodations are not consistently available along the Glenn Highway between Palmer and Glennallen. Starts have already been made toward such an end at scattered locations, and more activity may be expected along these lines as the tourist traffic increases. The advisability is indicated of making careful and immediate studies, to ensure that, on the one hand, adequate provision is made for the traveler's convenience, and on the other hand, that scenic values do not suffer through injudicious location of these needed facilities.

|

| Figure 34.—Seward Highway (Public Roads Administration photo). |

FUTURE ACCESS ROADS. Any study of the present road system of Alaska must consider further connecting links and contributory "feeders" which appear, however indefinitely, as future possibilities. Even though specific prophesy as to location or date of inception is impossible, there exist certain well-recognized deficiencies, satisfaction of which will influence the use of highways now in existence.

Seward Highway. On the Kenai Peninsula, north from Resurrection Bay at Seward to the south shore of Turnagain Arm at Hope, and largely through the Chugach National Forest, runs the Seward Highway, built by the Bureau of Public Roads, now the Public Roads Administration. Ultimate road connection from Hope to Anchorage has been considered, thus linking Seward with the Territorial network. The steep shores north and south of Turnagain Arm, together with the need for bridging that heavily-tided estuary, would involve costs beyond normal. Seasonal operation of a ferry between Anchorage and Hope might well prove less expensive, if connection is warranted.

It seems unnecessary to give special attention to facilities for recreational or vacation travel upon this highway unless this linkage is effected. The country traversed is scenic and recreationally usable throughout the entire area now accessible by road on the peninsula, a fact already recognized by hunters and anglers, and by the Forest Service. It will continue to serve as a recreational resource for residents of Seward, for tourists who stop over at that port, and, because of railroad facilities, for citizens of Anchorage and vicinity.

Glacier Highway. North from Juneau, along the east short of the Lynn Canal, runs a 30-mile road known as the Glacier Highway. Between its terminus and Haines lies the only impediment to continuous automobile travel from Juneau, capital city of the Territory, to Anchorage, burgeoning metropolis "to the westward," and to Fairbanks, central city of the Interior. Because Haines and Juneau are on opposite sides of the Lynn Canal, and because of steep slopes around its upper periphery, connection by road between the two cities appears unlikely at an early date. Northward extension of the Glacier Highway to a point near Berner's Bay would reduce the water interval materially and encourage ferry service over the intervening distance, even should the proposed ferry from Prince Rupert to Haines not become a reality.

Connection to Mount McKinley National Park. Mount McKinley National Park is recognized as an outstanding recreational resource of Alaska, but unfortunately for the traveler by motor car, it can be reached only by means of the Alaska R. R., a half-day trip from Fairbanks. In prewar years the railroad offered a service whereby passenger automobiles could be transported on flat-cars, from Fairbanks to McKinley Park Station and return, at a reasonable charge. There are, within the area, more than 80 miles of automobile road, unconnected as yet with the Territorial road system.

Two possibilities have been offered for effecting such a connection. One contemplates extension of the existing park road northward from its westerly terminus, down the valley of the Kantishna River to the Tanana, there to intersect a possible road from Fairbanks to Nome. Because of small likelihood of early construction of the latter, the Kantishna route does not appear currently feasible.

Consideration has been given to an approach from the Richardson Highway, the proposed road following old sled trails westerly from Paxson's to Denali, on the Susitna River, and to Cantwell, situated on the Alaska R. R., just south of the park. The distance from Paxson's to Cantwell by this route is about 125 miles. Possible mineral resources along the way strengthen this proposal.

Extension of this approach cross-country in an easterly direction from Paxson's to the Slana River and down it to join the Alaska Highway at Mentasta Lake has been suggested. A comparatively direct, albeit scenic route from Tok Junction and eastern points to the park would thus be assured. So far as is known, mineral resources between Paxson's and Mentasta Lake are not of present importance.

From joint consideration of the desirability of highway approach to the park and the possibility of tapping mineral resources along the most feasible route, it appears that the road west from Paxson' s should be undertaken whenever such action becomes possible, but that the link east to Mentasta Lake should be deferred to a much later position in the Alaska road program.

|

| Figure 35.—Natives by the roadside. |

Feeder Roads. As time passes, feeder roads will come into being, to facilitate reclamation and wise use of the natural resources of the region rendered more accessible by highway. The Bureau of Mines has been active in investigating potential supplies of critical raw materials throughout the Territory. Possibly deposits of sorely needed minerals may be discovered in the general locality of the Highway, in such quantities and sufficiently recoverable as to justify the construction of access roads. These would make possible the transportation of machinery and supplies to the mines, and of their products to processing plants or markets.

The Office of Indian Affairs welcomes the advent of the Highway as of material assistance to them in forwarding supplies to the Natives in the villages and reservations of the Territory. This procedure would be further facilitated by stub roads from the main highway to the reservations. Some improved means may be found necessary for crossing the river between the Highway and the villages of Tetlin and Tanana Crossing.

Indians of the reservations in the Southwest and in the Alleghanies have found it profitable to sell examples of native handicraft to the tourist and to pose as subjects for portraiture. The Indian of the Tanana is understood to have little interest in market-production of handicraft objects, preferring to depend on trapping and fishing. It may be that new-found familiarity with the tourist will result in acceptance and adaptation of customs followed by his more sophisticated brethren.

Moreover, there will be opportunity for him to guide and otherwise serve the parties of sportsmen for whom the main lure of Alaska will be its larger game-animals. It would not be difficult to imagine a series of sports headquarters scattered through the enclosing elevations of the Tanana, operated as private clubs or as commercial enterprises, and approached by road connections from the Highway.

The Tanana Valley is one of three regions in the Territory which are best adapted to agriculture. In its upper reaches east of Delta Junction, however, increasing elevation of the valley floor and its attendant effect upon temperatures and lengths of growing seasons may be accepted as indications that present techniques of farming will not prove uniformly successful. If these are improved, and without thought of forwarding another Matanuska project, the possibility suggests itself that some communities of predominantly agricultural character may arise in the Tanana Valley, either beside or removed from the Highway, as soil conditions and slope orientation may dictate. "Farm-to-market" roads of the States may have Alaskan counterparts.

|

| Figure 36.—Experimental farm at the University of Alaska. |

If the apparent agricultural possibilities of the Tanana Valley region are substantiated, experiment stations there may well be considered, especially since climatic conditions will not coincide with those at College, the site of the parent station. In point of fact, installation of simple facilities for agricultural research would perhaps be of great value, in that determination of the agricultural potentialities of the region would be available in advance of homesteading operations. From this availability the Government would benefit no less than the homestead aspirants.

Perhaps the timber resources of Interior Alaska would not justify commercial operation if forests of larger growth or more desirable species were close at hand. They will serve many local needs in lieu of foreign timber imported at considerable costs. Sawmills are indicated, and even small plants for fabricating wood products. Sympathetic consideration for scenic values suggests that such mills or plants be located in the hinterlands, and not directly upon the Highway. Access roads again enter the picture.

Procurement of fuel wood is a problem in Alaska, as paradoxical as the statement may appear at first glance. In common with all commodities which need local labor for production or preparation for the market, its cost to the consumer is high. Because of the length and severity of the winter season in Interior Alaska, fuel quantities required for home fires appear fantastic to those who are familiar only with more temperate climes. The homesteader is able to combine necessary clearing operations with laying-by his winter fuel; such a course is not open to residents of populated centers.

The suggestion has been made that suitable tracts be set aside from the public domain, in the near vicinity of communities which are already existent or may be expected to develop, and that community dwellers be permitted to harvest their winter fuel from these tracts, in conformity with requisite and reasonable principles of forestry. As in the case of commercial timbering operations, these public woodlots should be so located as not to detract from the merit of roadside views.

NEXT >>>

Last Modified: Mon, Sep 6 2004 10:00:00 pm PDT

http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/alaska/chap3.htm

![]()

Top

Top