.gif)

Recreational Resources of the Alaska Highway and Other Roads in Alaska

MENU

Provisions for Recreational Use

A Plan for Recreational Facilities

|

Recreational Resources of the Alaska Highway and Other Roads in Alaska

|

|

Chapter I:

THE ALLURE OF ALASKA

Why has Alaska drawn travelers for recreation to itself as a magnet, through the years, and why will this attraction persist and increase after it is no longer imperative that all energies of the nation be directed toward successful prosecution of the war in which we are now engaged?

|

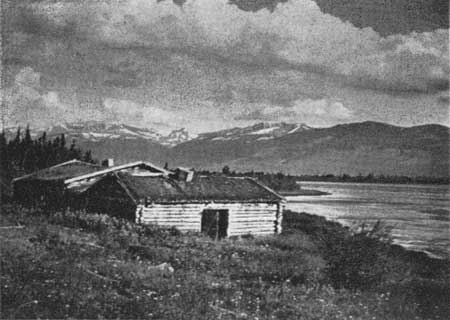

| Figure 9.—Mentasta reflections. |

PUBLICIZED OPERATIONS. Publicity attendant upon construction projects and operational undertakings has always encouraged recreational travel. Extra miles are driven by tourists to view the largest earth-filled dam, the longest suspension bridge, the busiest open-pit mining operation. The term "publicity" as here used refers not only to paid advertisements, editorial comments, and reviews in technical publications, but also to that received orally and in personal correspondence from friends and relatives who have participated in or witnessed the project or operation.

No other activity connected with the Territory in recent years has been publicized as has the Alaska Highway. Press releases to the newspapers have detailed the difficulties surmounted by engineer troops; scientific articles have covered the part played by the Public Roads Administration and its accessory contractors; thousands of persons have heard parts of the saga of the Highway from fathers or brothers, sweethearts or friends, who have fought muskeg with engineer troops or ridden the bucking tractors of contractors. The Highway has been glamorized. It is safe to say that, at one time or another, the owners of at least a quarter of the more than twenty million passenger automobiles in the States have dallied with thoughts of taking the much-publicized trip to Alaska within the next few years after the war.

Less in the public eye than construction of the Highway, but nevertheless acquainting thousands with some part of the story of Alaska, are other military activities which have centered there. Officers and enlisted personnel of Army and Navy units stationed in the Territory have pictured to the home folk, so far as censorship regulations would permit, the terrain, surroundings, and people that have been parts of their daily lives. Perhaps the very fact that full description has not been possible in letters will render more lively and enduring the desire of families to see for themselves the locale of the MP station manned by their Corporal Johnny or the pier to which Seaman Bob's Coast Guard home was moored.

Normal pursuits of life in Alaska in peace-time have also received much publicity in prewar times. Agricultural colonization in the Matanuska Valley was the subject of lively discussion in the States during its early operation and until superseded by war-interest. With highway access from the east to the Valley possible for the first time, inspection is probable by tourists who have retired from agricultural labors or who recall youthful days spent in rural environment. This is to be understood not to refer to those whose motivating purpose in visiting Matanuska is to investigate its possibilities as a permanent home, but rather to those whose interest in the experiment there conducted lies in what others are accomplishing more than in what they might do personally.

Since the days of '98 Alaska and gold have been associated, even in the minds of those whose acquaintance with both has been slight. Fisheries and fur industry of the Territory are comparable in value with its mining activities, but have not so captured public interest. The lure of yellow gold persists, even though it has been supplanted as the most precious of metals. Extensive placer mining operations easily reached from Fairbanks and the large lode workings at Juneau will continue to draw lively interest from the tourist, perhaps on a more extensive scale than they have in the past, because of the increased number of visitors.

LOCATION AND CLIMATE. Alaska's geographical position may be somewhat vaguely fixed in the mind of the average citizen. He may not realize that its area is one-fifth that of the forty-eight states, that Ketchikan is not as far west of San Francisco as Salt Lake City is east, while Attu is nearly as far west of Hawaii as that island is west of San Francisco, or as San Francisco is west of St. Louis. He is quite sure, however, that Alaska is the most northerly land over which the Stars and Stripes fly, the nearest highway approach to the North Pole on this continent.

He will not be able to cite the normal population of the Territory as about 75,000 persons, roughly that of Portland, Me., or of Charleston, S. C., but he will know that Alaska is sparsely settled, that it includes great areas which bear no evidence of human habitation save for scattered groups of aborigines, in short, that it is the last remaining great frontier region of our country, imbued with all the romance that the term connotes.

"Land of the midnight sun" is a designation to fire the imagination. In parts of Alaska it is literally applicable at the time of the summer solstice. Even in the southerly reaches of the Territory daylight hours in the summer season are such as to permit sightseeing for as long each day as the tourist may desire or his strength allow. So far as the visitor is concerned this fact may be regarded as one of Nature's automatic compensations for the travel season in such northerly latitudes begins later and ends earlier than in the States. Therefore the tourist who plans but a single trip to Alaska and wishes to see all that is possible during the time at his disposal will arise early, to find that the sun has preceded him, and defer selection of his resting-place for the night much longer than his custom.

Over much of those portions of Alaska now reached by highway the summer weather is admirable for travel. Temperatures do not vary sharply from those experienced in resort regions of the States. In the Interior, precipitation is normally light, with sunny days predominant during the summer months. Only when approaching the sea-coast does the traveler ordinarily have occasion to accommodate his plans to weather conditions. Here, in vegetative surroundings known as "rainforests", clear days are in the minority and sunny days are to be greeted with enthusiasm.

|

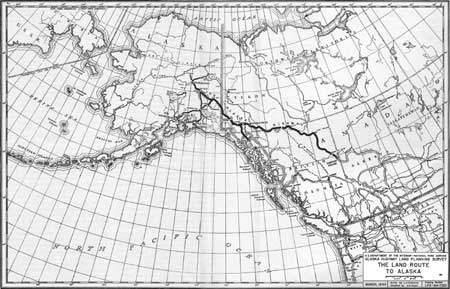

| Figure 10.—The Land Route to Alaska. (click on image for a PDF version) |

SCENIC VALUES. Tourists are drawn to any particular section of the earth's surface by curiosity concerning its inhabitants, their activities and ways of life, and by seasonal climatic circumstances more pleasing than those to which they are accustomed at home. The summer exodus from city heat to comparative coolness of mountain or seashore finds its winter counterpart in migration from the ice and snow of northern homes to sun-drenched beaches and rustling palms of Florida and Southern California.

Beyond these attractions is the urgency to visit surroundings dissimilar to wonted environments, and particularly those distinguished as of unusual scenic attractiveness. Of these there is no dearth in Alaska. Mountains, glaciers, rivers, lakes, and forests all combine to render it a land inspiring more than the usual complement of "Ohs" and "Ahs".

The Alaska Range lies crescent-wise athwart the southern portion of the Territory, dominated by Mount McKinley, mightiest monarch of the North American continent, towering 20,300 feet toward the zenith. From its eastern extremity the Wrangell Mountains lead to and tie in at the Yukon boundary with the giants of the St. Elias Range. Of these Mount Logan and Mount St. Elias cede precedence only to Mount McKinley. Westward from St. Elias the Chugach Mountains skirt the Gulf of Alaska as far as Anchorage, at the head of the Kenai Peninsula. West of Anchorage the Aleutian Range picks up, following the Alaska Peninsula southwest, gradually diminishing and at last vanishing into the sea at the western end of the Aleutian chain of islands. These and many others worthy of specific mention not possible here are objects of note to the visitor, whether viewed from highway, railroad, boat, or plane. As the higher peaks and crests are perpetually snow-clad a favorite pursuit of the tourist is to watch the snow line creep daily lower as the season advances and late summer merges into autumn with its promise of winter rigors to come.

As might be expected in the latitude of Alaska tremendous ice fields are found at the high elevations, particularly in locations such that high tablelands are largely enclosed by surrounding peaks. These ice fields, building up until they spill through between the circumscribing heights, are the genesis of glaciers which wend their inexorable albeit sometimes almost imperceptible course to the sea, where they discharge as bergs, or to lower elevations inland, where their melting faces become sources of rushing glacial streams. Among the larger glaciers are Malaspina and Bering which flow south into the Gulf of Alaska, and Columbia which debouches into Prince William Sound. Some of the smaller but not less interesting examples, better known to the general public because of easy accessibility, are Mendenhall, but a few minutes drive from Juneau over the Glacier Highway, and Worthington, its face plainly displayed within 500 yards of the lower Richardson Highway. Glacier Bay National Monument, in Southeastern Alaska, includes within its confines the Fairweather Range, Brady Ice Field, and numerous glaciers whose faces may be approached at short range by boat through forded inlets into which are cast their discard of bergs.

Among the rivers of Alaska none has more romantic association than the storied Yukon, immortalized by the pens of Robert Service and others. One of the longest navigable rivers in the continent, it bisects Alaska in its course, first northwest and later southwest, from its source in the Yukon Territory to Bering Sea. It is interesting to note that at Whitehorse, head of navigation, only 111 miles by rail from the Alaskan port of Skagway, the traveler by boat is nearer to the ocean than at any point until he approaches Bering Sea.

Important tributaries to the Yukon are the Porcupine and Koyukuk from the northeast, and the Tanana from the southeast. Major rivers not tributary to the Yukon include the Kuskokwim flowing southwest into Bering Sea, the Susitna which empties southward into Cook Inlet just west of Anchorage, and the Copper which finds its way southward to the Gulf of Alaska near Cordova.

Discounting air travel, which makes all scenic resources easily available, the usual tourist will see the Yukon only by river boat, the Susitna from the Alaska Railroad, the Tanana and Copper from the highways, and other of the major rivers mentioned not at all.

Many of the lesser streams of Alaska, and to some extent the larger ones, are "fast water." In the sections most easily reached by tourists, namely Southeastern Alaska and the southeast quadrant of the areal mass west of the 141st meridian, glacial streams predominate, their waters characterized by milky cloudiness and comparative opacity as they tumble toward the sea.

Lakes and ponds are plentiful in Alaska, widely scattered and diverse in size and nature. Iliamna, lying across the head of Alaska Peninsula, is more than 75 miles in length and attains a width of 20 miles. Tanana's broad upper valley is studded with thousands of lakes from Tetling, the largest in this vicinity, to the Yukon border. From aloft on a crisp, sunny morning in late August the scene is breath-taking, a fantasy of turquoise and cobalt gems strewn upon a soft background of Chinese rug simulated by the russets, golden browns, and yellows of deciduous autumnal foliage. Many of the smaller lakes are so shallow as to freeze solidly during the severe winters of the Interior, thus becoming untenable for game fish and detracting from the charm which they would otherwise hold for devotees of rod and reel.

|

| Figure 11.—Through birch and aspen, west of the Yukon boundary. |

The tourist who pictures Alaska as a desolate waste, devoid of vegetation, will needs revise his concept. It would be as absurd to assume that the entire Territory is clothed luxuriantly in forest. Timber line is lower than in more southerly latitudes, and in summer bands of naked rock intervene between lower spruce-enveloped slopes and snow-tipped summits. Rain forests encircling the Gulf of Alaska and extending southward to include much of Southeastern Alaska are similar to those along the north Pacific coast in the States, except that they are punctuated and enlivened by glaciers. The impression gathered is one of lush growth, in both forest cover and under-story. Streamers of gray moss hang from the trees and no impossible strain of imagination is required in some locations to transform towering spruce to spreading live-oak and the locale from "Arctic" (!) Alaska to the bayou country about New Orleans. Sitka spruce harvested from the rain forests of Alaska is playing a role in the program through which the Allied Nations are winning dominance in the air.

Along the route of the Alaska Highway, through the Tanana Valley southeastward from Fairbanks, forest growth is less impressive. Spruce here is also predominant, but less grandiose in scale, the general effect being that of even, dense distribution of poles 6 inches to 8 inches in diameter and of relatively uniform height. Passage along the arrow-straight flight of level road tangents cut through solid growths of this nature is apt to be come monotonous and even depressing, particularly if unrelieved by evidences of human habitation or by occasional views of distant mountains.

Approaching the Yukon boundary the scene lightens; the country is more rolling, and the lighter summer green of birch and aspen enlivens the funereal sombreness of spruce. Commercial utilization of timber here on an extensive scale appears doubtful unless local industries are developed to fabricate small articles. Fuel use of wood is an important factor throughout Alaska.

|

| Figure 12.—Grizzly bear, Mount McKinley National Park. |

WILDLIFE. The visitor in an unfamiliar land is always interested in its beasts of the field, birds of the air, and creatures of the sea. He is delighted to recognize those to which he is accustomed at home, and curious to discover the habits and characteristics of those new to him, especially if he has learned of the latter through hearsay or study or casual reading.

It is not within the province of this report to recite or catalog all species which are found in Alaska, but mention may well be made of a few which will not be encountered normally by the tourist in his home surroundings, and which he may be interested in seeing.

The ubiquitous black bear, the grizzly, and the Alaska brown are all found in the Territory. By popular impression the grizzly is accorded the dignity of "fiercest of his kind"; yet the Kodiak brown bear is tougher, fiercer, and larger, reputed to be the largest carnivorous land animal in the world. The habitat of the polar bear is beyond those sections usually reached by the tourist, so that few of the species will be seen.

Deer, moose, caribou, and reindeer tenant various ranges in Alaska. Mountain sheep and goats are found particularly in the rocky fastnesses of the southeast quadrant. The bison colony established in 1928 in the vicinity of Big Delta is reported to be doing well. Fox, marten, mink, otter, ermine, and beaver are among the fur-bearers trapped each year to values of several millions of dollars. Fur farming, the raising of foxes in captivity, has been an important industry, and will perhaps be revived in postwar years.

Among the predators common in the Territory may be listed wolf and coyote, the advent of the latter attendant upon human migration from the States. Control of these animals, inimical to the interests of fur industry and big-game hunter alike, has been a subject of bitter controversy in Alaska.

The traveler by sea will witness the sleek emergence of sealheads and may glimpse the feathery drift of spume betraying the subsurface presence of a whale. The sea otter is now so rare, except in the western Aleutians, that he will probably view its beautiful pelt only in museum exhibits. He will catch flashes of silver as 3-foot salmon leap clear from and return to their native element. Ashore, in his traverse of the highways, he will cross many streams abounding in grayling, the sport fish most numerous throughout the Territory. Dolly Varden and rainbow trout will test his mettle, the latter sometimes reaching 12-pound size.

Migratory waterfowl are abundant in Alaska. Their nesting areas are in comparatively isolated locations, and thus protected. Glacier Bay National Monument is reputed to be one of the few nesting places of the eider duck.

|

| Figure 13. Matanuska Glacier. |

OPPORTUNITIES FOR SCIENTIFIC STUDY. Numbered among visitors to the Territory will be those who are attracted, not by curiosity as to the aspect of the country and achievements of its inhabitants, but by the deeper desire to know and to understand natural phenomena which are apparent as the planet which we inhabit follows its infinite pattern of development. Opportunities for scientific study are manifold in Alaska.

It is a new land, physiographically speaking as well as in the sense of human occupation. Many of the processes now evident were factors in shaping the terrain of the States in bygone centuries. Land forms have not assumed the comparative stability of those in older sections of the world. Object lessons are easily found to typify processes which must be discovered by reasoning elsewhere. In Alaska glaciers still scour and transport gravel, volcanoes still smoke, rivers struggle toward their ultimate channels, alluvial fans are built up in seeming contradiction of gravitation. Its value to students of physical geography as a laboratory for research and demonstration purposes is apparent.

Many geographical changes are based upon geological reasons. The practical application of the science of geology usually associated with Alaska is the determination of location and recoverability of deposits of precious or critical minerals or petroleum. Abstract geology goes far beyond that. Lessons learned from exploration in one part of the world may prove applicable to sites far removed. Data acquired as a by-product of current mineral investigations in Alaska may add materially to the world's store of basic geological information.

Evidences of volcanic action abound in Alaska. Outlines of blown-out craters are plain, even to the casual traveler without scientific training or lore. The Wrangell Mountains are of volcanic origin, built up of lava and volcanic mud. Mount Wrangell itself, 14,000 feet in elevation, is still active and occasionally wreathed with smoke.

Within the confines of Katmai National Monument is a spectacular association of volcanic phenomena. The Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes, characterized by its myriad fumaroles or jets of steam, exemplifies a prior stage in the development of the famous geysers of Yellowstone. Mount Katmai, previously inactive, erupted with great violence in 1912. Within its snow-capped crater lies a milky-blue, mile-long lake, pierced by a small crescent island.

Nonprofessional tourists are impressed by glacial displays in their static aspect. Interest of the scientist lies more in habits of progression and recession, and in the effects of these habits in shaping the form and outline of the earth. Several scientific expeditions have explored and studied Glacier Bay National Monument and have recorded for their successors data there obtained. It may also be noted that the area has been used by the United States Army as a testing ground for various types of Arctic clothing and equipment.

Opportunities for biological study are everywhere in Alaska, whether in the fields of botany or of zoology. Much work has been done by governmental agencies concerned by threatened extinction of some of the Territory's most valuable commercial assets; much more remains to be done.

A mistaken popular notion persists that Alaska is a land of boundless and inexhaustible resources of animal life, where it is only necessary to step to the door for a bear steak "on the paw" or to the shore for a salmon steak "in the scales", and where such withdrawals will be automatically replaced. Such is not the case. Bountiful as they are, these resources must be husbanded and administered under suitable and necessary regulation, else they will dwindle and be lost forever. Further zoological research is indicated as a basis for regulation.

Research work in botany is needed to increase the world store of knowledge concerning Arctic and sub-Arctic flora and to provide timely and authentic information to settlers who will seek to grow, in Alaska and for Alaskans, the agricultural crops needed to support its augmented population. The parent experiment station near Fairbanks has done much along these lines; location of sub-stations in newly-accessible regions of possible agricultural value appears a desirable venture; experimental work in plant breeding, hybridization, and determination of resistant varieties suggests itself.

Alaska's climate is variable, as regards both temperature and precipitation. This is due to many causes beyond mere geographical extent. Variations in relief and proximity to currents moving in and over the Pacific Ocean may be cited as specific influences. Southeastern Alaska is blessed with an equable climate, hardly ever below 0° in winter or above 90° in summer. In those portions of the Interior commonly reached by the tourist, however, particularly in the valley of the Tanana River, the range is increased to a considerable extent, summer temperatures of more than 100° and winter readings of -76° having been recorded officially.

Rainfall is heavy in Southeastern Alaska and on the coastal slopes of the mountain ranges bordering the Gulf, but decreases rapidly north of these ranges. In the vicinity of Ketchikan the average precipitation is more than 12 feet, while in the Tanana Valley at Fairbanks it is approximately as many inches. The proportion of this precipitation which is in the form of snow varies from less than one-tenth in the southeast to nearly all in the Arctic region. Point Barrow records some snowfall in every month of the year.

Such variations are advantageous for studies in climatology and meteorology in general, whether by interested amateur or professional scientist. The accumulation and analysis of meteorological data is especially important to Alaska because of the value of accurate weather forecasting in a land where transport is so largely by airplane and the growing season is so short. Great benefit will ensue from readings taken by military units located in places where maintenance of a civilian observer has been economically impossible. Perhaps with increased accessibility and attendant augmented population there will come improved facilities for weather research.

Students of ethnology have found Alaska worthy of search for data to confirm hypotheses concerning human movements and of study to determine results of racial admixtures. There is the theory that Man's first advent to this continent was from Asia across the narrow Bering Straits which separate Siberia from Cape Prince of Wales, and that later progress was eastward across Alaska and southeast to more temperate climes. Evidences to support this theory have been sought with relatively little result to the present time.

Natives of the Territory have been grouped in general as Indians of Southeastern Alaska, mainly Tlingits, Athapascan Indians of the Interior, the Aleuts of the island chain, and the Eskimos, whose habitat is largely north of the Kuskokwim and Yukon Rivers. Much study has been given by scientists to the derivation of these peoples, to the manner in which each ethnic group has retained its individual character, and to the lessons which their methods of life have taught to the incoming white settlers, lessons which have made survival of the settlements possible and successful.

|

| Figure 14.—A page from Alaska's past. |

HISTORICAL ASSOCIATIONS. Many and gripping are the tales which linger of Alaska in the making, of the historical antecedents of the Territory as it exists today. Some have been gross exaggerations, tongue-in-cheek recitals which have acquired the flavor of truth through repetition; others, so improbable as to be remembered for their Munchausen-like quality, are as apt as not to be accurate narrations of actual incidents. In Alaska it is hard to know what or how much to believe.

Most of the historical associations which prompt visits to and travel in Alaska center around either the period of its existence as a Russian colony or the days of the Klondike gold rush at the turn of the century.

Establishment of Russian trading posts in Alaska was accomplished soon after the 1741 voyage of Vitus Bering to its shores. The first permanent settlement was made on Kodiak Island in 1784. The interest of the early trader-explorers was almost entirely in furs and their treatment of the Aleuts so harsh that in 1799 individual franchises were withdrawn and exclusive rights granted to a new trading corporation, the Russian American Co., which ruled Alaska, to all intents and purposes, until 1862. The great period of Russian expansion was under Alexander Baranof, chief director of the company until his death in 1818. Moving his headquarters from Kodiak to Sitka in 1805, he there established a brilliant capital, from which trading posts and settlements extended from Bristol Bay to California.

After Baranof's death and with waning of Russian activity there came increased interest from other quarters. American whalers and trading vessels operated openly in Alaska and a Western Union Telegraph expedition began surveys for connection by cable overland, except for the narrow width of Bering Straits, between the United States and Europe. The project was abandoned in 1867 when the Atlantic cable was successfully operated.

At this time Russia was more concerned with home affairs than in defending such an outlying empire. Alaska was sold for $7,200,000 and the American flag hoisted at Sitka on October 18, 1867. The Russian influence is still reflected throughout the Territory in geographical names reminiscent of the explorers and administrators of that nation, and in churches ordained by them which have persisted to the present day.

First discovery of gold in Alaska was in 1850, in the Kenai River basin. Productive mining has been carried on near Juneau since 1880. To the average person gold, Alaska, and the Klondike are related, perhaps because of the writings of Robert Service, Rex Beach, Jack London and others who took part in the rush of 1898 to Dawson, after the great Bonanza Creek "strike." Dawson actually is not in Alaska but in the Yukon Territory of Canada, at the junction of the Klondike River with the Yukon. Established in 1898, it became almost immediately the center of life for 30,000 fortune-seekers, as well as the Territorial capital.

Although in Canada, Dawson was best reached from Alaska. A particular aura of romance lingers over the approach from the port of Skagway, a hazardous journey fraught with severe hardships. From there the mountains could be crossed either through White Pass, traversed since 1900 by narrow-gage railroad, or through famed Chilkoot Pass, gained by steps cut in the icy 45° slope. From these passes the trails dropped to Lakes Bennett and Lindeman respectively, and to the most dangerous part of the journey, by hastily constructed boat, through the rapids of Miles Canyon to Whitehorse, whence water travel to Dawson was comparatively simple.

It was possible then, as it is today, to travel all the way to Dawson by water. From the States the route crossed the open Pacific and Bering Sea to the mouth of the Yukon and upstream to the Klondike. Fortune-seekers, in frantic haste to reach fabled Dawson, gave scant heed to the easier but slower all-water approach. Hulls of Bonanza King and other famous river boats, abandoned after the rush, rot at the piers of Whitehorse today.

Thousands attempted the overland trek from the coast at Valdez, hoping to avoid payment of duty to the Canadian government. Most of them perished or returned destitute to Valdez. Sent out to prospect the possibility of this trail connection, Capt. William R. Abercrombie did much to explore and map the area and to find a way to the Interior.

He planned a road from Valdez to Copper Center, through Keystone Canyon and Thompson Pass, much as the Richardson Highway now exists. From Copper Center, following Copper River and the old Eagle Trail, crossing the Tanana River near the present Tanacross airport, access to Dawson would have been through Eagle and the Forty-mile country.

Russian period and gold-rush days are recognized phases in the development of Alaska, fascinating because of their tales of hardy achievement, of obstacles overcome, and of commensurate rewards to those who survived the rigors encountered. Who is to say, in retrospect, that activities on Alaskan soil and in Alaskan waters during the present world conflict have not merited similar consideration in the pages of history?

Much is already public knowledge, the pioneer construction of the Highway, the strategic location of Fairbanks at the northern crossroads of the air, the epic sagas of Attu and Kiska; much remains yet to be told. Certain it is that future travelers to the Territory will wish to see first-hand some of the scenes of stirring events of such significance.

SUITABILITY FOR OUTDOOR PHYSICAL RECREATION. Those who like to hike will find many chances in Alaska for the healthy pursuit of that avocation. Development of the Territory has necessitated much travel by dog-sled, and let it not be thought that such travel exercises only the dogs. Although most tourists will visit Alaska during the off-season for such expeditions, they will be able, if they so desire, to follow on foot some of the trails which have had a part in making the Alaska of today. For them it will not be the hazardous "make-it-or-else" adventure of their predecessors. Alighting from motor-cars, they may elect journeys as brief or as protracted as may be dictated by tastes, physical condition, supplies, or equipment.

For those who may be addicted to the conquest of elevation, the field of choice is as broad. The novice may hike on Sunday from the docks at Juneau to the top of Mount Juneau, back-drop for the city, there to gaze upon the southward fling of Gastineau Channel and its encircling moderate heights. At the other end of the scale the experienced Alpinist will find dozens of peaks as worthy of his mettle as any which he may have attempted in Switzerland. Mount Sanford, with an elevation of 16,210 feet, was climbed first in 1938; Mount McKinley, highest on the continent, resisted all attempts to scale its 20,300 feet of altitude from 1903 until 1913. A single midsummer view of the cold stillness of these distant, snow-capped monsters is enough to remind ordinary mortals of their own insignificance and to inspire in seasoned climbers the desire to surmount the challenging heights.

The huntsman and the fisherman will find in the Territory species which they have not stalked or cast for at home, and will be impressed by the number and size of specimens of kinds with which they are familiar. Distribution and variety of game have already been touched upon; it is enough to reiterate that hunting and fishing in Alaska are good, but that principles of conservation must not be disregarded if they are to remain so.

Photography is not usually classed as a strenuous activity. However, it is an adjunct to enjoyments which are. Huntsman, fisherman, and mountain-climber alike desire to record and to substantiate accomplished feats. Even when pursued as an end in itself, photography is apt to entail a considerable amount of exertion if the best pictorial results are to be obtained. On occasion, good photographs may be snapped from speeding plane, or boat, or train, or automobile, but the seasoned photographer will often find his most interesting subjects far afield. He will deem it necessary to go to great lengths and to exert himself beyond the normal to obtain viewpoints and acquire pictures which are distinctive and out of the ordinary.

NATIONAL PARKS AND MONUMENTS. Increased public familiarity with the units which are comprised in our federal system of parks has tended to cause thoughtful vacationists to accept such areas as objects worthy of inclusion in travel itineraries. There are five of them in Alaska.

Mount McKinley National Park includes within its 3,030 square miles the highest mountain in North America. From its drives the tourist will be able to view animal life in greater numbers and in more variety than from any other road in Alaska which he may travel. The park is located in the south central part of the Territory, and reached by the Alaska R. R. between Fairbanks and Anchorage. Facilities for accommodation of the public are normally available.

Glacier Bay National Monument is one-fifth larger in area and contains the Fairweather Range as well as tidewater glaciers of first rank. Much of its shore is heavily timbered. Located in Southeastern Alaska and bordered in part by the Pacific Ocean, the Monument is not yet developed for accommodation of visitors, and is accessible only by plane or boat, without regularly scheduled service.

Katmai National Monument covers more than 4,200 square miles and borders Shelikof Strait near the head of the Alaska Peninsula. It is a wonderland of scientific interest in the study of volcanism, including the famed Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes. Accessibility and visitor facilities are as limited as at Glacier Bay.

Old Kasaan National Monument covers only 38 acres but includes an abandoned Haida Indian village in which remain totem poles, grave houses, monuments, and parts of the original framework of buildings. It is reached by launch from Ketchikan.

Sitka National Monument is an area of 57 acres, within walking distance of the city of Sitka. Like Old Kasaan it is of historical significance, the site of an ancient village of Kiki-Siti Indians. A Russian midshipman and six sailors, killed in the decisive "Battle of Alaska," are buried there.

|

| Figure 15.—Mount McKinley (Sackman photo). |

NEXT >>>

Last Modified: Mon, Sep 6 2004 10:00:00 pm PDT

http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/alaska/chap1.htm

![]()

Top

Top