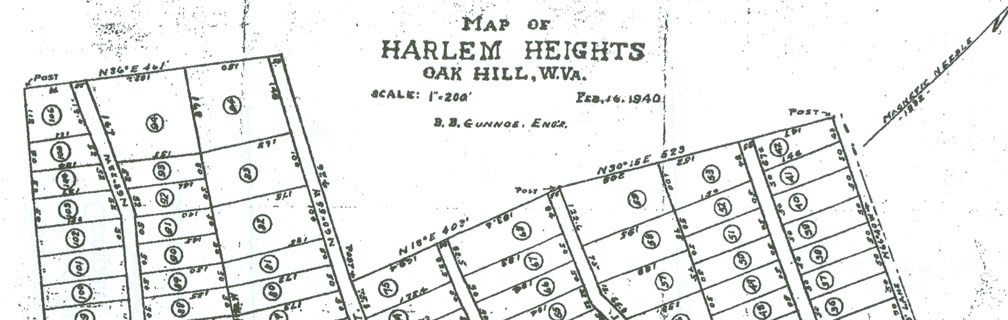

Harlem Heights is an atypical African American community located within the City of Oak Hill, West Virginia. While most African American communities in the New River area were coal mining or industrially-based, the residents of Harlem Heights had a variety of occupations. In addition, the residents of coal mining towns usually lived in company houses, but most residents of Harlem Heights were homeowners.1

photo courtesy of Betty Sims Brown “[Harlem Heights] had five black families when I moved there in 1942. The remainder of the area was farm land. The section they called Harlem Heights had actually three streets. Lincoln Street, High Street, and Lewis [street]. [At that time] everything was inaccessible. We had the old fashioned outhouse for quite a while. We had about two wells with this huge long bucket you draw with. We had to carry our water [and] catch rain water for laundry. We had it rough for about a couple of years.” 2 As the community began to develop; paved roads replaced dirt roads. Residents acquired indoor toilets and running water as well as other amenities and services. As the population grew, the community needed a school. In 1947, the Harlem Heights School was built and accommodated students in the first through eighth grade. High school students were bused seven miles to DuBois High School in Mount Hope, West Virginia. When schools were integrated in the 1960s, Harlem Heights students began attending the white elementary schools and Collins High School in Oak Hill. The school at Harlem Heights closed its doors in 1967.3

photo courtesy of Betty Sims Brown The people of Harlem Heights took pride in their community by keeping it clean and attractive. They actively supported their churches, civic clubs, and fraternal organizations. Some residents worked as community activists to move their neighborhood forward. In the 1970s, social worker Opal Leggett was responsible for starting and overseeing the Head Start program in Fayette County. Fayette County Legislators, Diane Smallwood and Reverend Frank Robinson as well as the honorable William Robinson were active as political organizers and community developers.5 For his impact in the community and as a professional basketball player, a neighborhood park was built in honor of federal mine inspector Russell E. Mathews.

photo courtesy of Betty Sims Brown 1. Ancella Bickley, To Black in Fayette, (Fayetteville: The Centennial Committee of the Second Baptist Church of Fayetteville, WV and the Fayette County Black Caucus, 1993), 52. 2. Ibid, 52-53. 3. Interview with Terrance Tango Leggett by John Bollinger NPS, 11/ 30/ 2015. Also, Bickley, To Be Black in Fayette, 52-58. 4. Interview with Tango Leggett. 5. Ibid. 6. Bickley, To Black in Fayette, 58. |

An official website of the United States government

Here's how you know

Official websites use .gov

A

.gov website belongs to an official government

organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS

A

lock (

) or https:// means you've safely connected to

the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official,

secure websites.