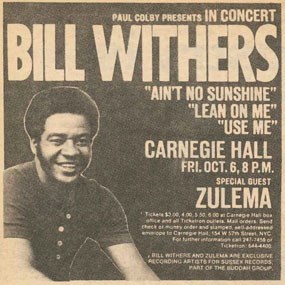

“Those Who Came Before, was written and performed by me, Lady D. It tells of my days growing up in West Virginia. Over the years, musicians like myself, Bill Withers, The Swan Silvertones, and many others have kept the essence of African American music alive in West Virginia and the nation. “I was born in Kayford, WV. They call me West Virginia’s First Lady of Soul. I am a singer, song writer, and actress, and I perform a variety of soul, blues, jazz, and gospel songs." Lady D, Beckley, WV

The Swan Silvertones, an African American gospel group, was formed in 1938 by Claude Jeter, a West Virginia coal miner. Known for their sweet harmonic sound with soulful vocals, the group recorded over 100 titles, its most famous being “Mary Don’t You Wait” in 1959. One of the greatest influences on American music has been the African rhythms and melodies that came to America with enslaved people. Though the years, the blending of these rhythms and melodies with those from Europe formed new and distinct musical sounds. Today we know these sounds as gospel, ragtime, soul, blues, jazz, and old-time country music. During the years of enslavement, African Americans developed songs of work and songs of worship using the rhythms and melodies carried over from Africa. Known as “Negro spirituals,” they expressed the longing of enslaved people for spiritual and bodily freedom, for safety from harm and evil, and for relief from the hardships of enslavement.1 By the 1870s, spirituals began to be seen as music that revealed the beauty and depth of African American culture.2 In the early 1900s, the performance of “Negro spirituals” became a tradition among black singers.3

Gifted singers within the black community could be counted on to improvise four-part harmony for the gospel hymns on Sunday morning.4 During the week, African Americans continued to express themselves through a variety of work songs like those used to synchronize the work of railroad track liners.5 Rhythms and melodies were also passed from generation to generation. Many black musicians were self-taught, while others learned as apprentices from the best fiddle player or banjo picker in the community. Many types of music were enjoyed as part of African American life in company towns. One of the most important was “The Blues.” The Blues, like the spiritual, is a product of slavery developed from African American work songs and European American folk music.6 Other varieties of music included string bands, gospel, quartets, and jazz. In the 1930s, big band jazz and dance music came to West Virginia; it was form of musical entertainment enjoyed by black mountaineers. Generally, music was played simply for enjoyment and relaxation. It was performed by musicians and singers who may have dug coal side-by-side during the day and then performed together at their neighbor’s house in the evening. 1. Lori Brooks, Berea College, Cynthia Young, The History of African American Music (The Gale Group Inc., 2003), http://www.encyclopedia.com 2. Ibid 3. Ibid 4. Christopher Wildinson, Big Band Jazz in Black West Virginia, 1930-1942, University Press of Mississippi, Jackson. 2012. 5. Ibid |

Last updated: January 22, 2020