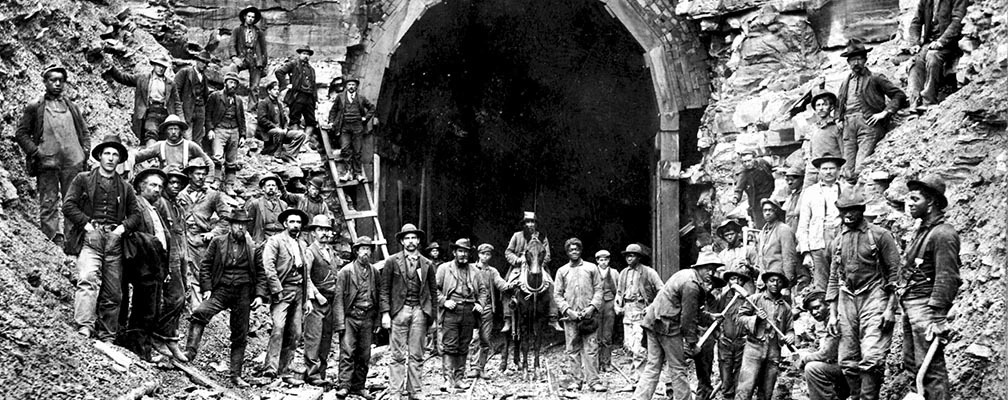

C&O Historical Society The soundscape of a national park is often filled with bird songs, wind, and rustling trees. At New River Gorge, if visitors stop to listen, they will hear more than the sounds of nature. Intertwined with nature visitors may hear the whistle of a train. The Building of the RailroadWhen the railroad came to New River Gorge, it shaped the modern history of the area. Southern West Virginia was an isolated area with a small population of farmers. The railroad opened the region to the rest of the world and changed it forever. Instead of only subsistence farmers, industries sprang up throughout the gorge. Workers came from all over creating diverse populations. Coal mines and logging companies harvested natural resources from the West Virginia hills. These resources fueled the United States' Second Industrial Revolution and the modern era. The Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad built their main line between 1869 and 1872. In New River Gorge hundreds of men worked to complete this vital link to the outside world. Two groups of men primarily worked on the railroad. Thousands of freed African-American slaves and Irish Catholic immigrants. Both groups wanted to start new lives for themselves and their families as new citizens. Building through such rough terrain was a monumental undertaking. The railroad would stretch from the border of Virginia to the Ohio River. It had to cross the rugged Appalachian mountains and New River Gorge was the easiest path. Like the Transcontinental Railroad, the C&O built the railroad from both ends of the state. Although the gorge is a natural corridor, there were still barriers like rocks and cliffs. For three years, workers dug and graded rail beds. They drilled and blasted tunnels, built bridges, and laid tracks. Horses and mules helped carry the heaviest loads, but most work was human-powered. Using only hand tools and explosives, these men carved the way through the mountains.

NPS The Birth of a Legend

Out of this tremendous undertaking a legend emerged. This legend became one of the greatest in world folklore - John Henry, "The Steel Driving Man". The John Henry of legend is more myth than man. A tragic, larger than life hero involved in an epic battle between man and machine. The popular folk song "The Ballad of John Henry" immortalized his story. Although there have been many versions, they all tell the same story. The song sings of a little boy, John Henry, who was born with a fateful vision of a "hammer in his hand". When he grew older, John Henry became a steel driver. The company bought a steam drill to replace the steel drivers saying it would be faster. John Henry famously said "A main ain't nothing but a man" and challenged the machine to a contest. He vowed he'd die before he let the machine beat him. The champion of the working class, John Henry and his shaker faced down the machine. Whichever team drilled further in a period of time would be the winner. At the end of the contest, John Henry drilled further and struck a win for working men everywhere. The exertion proved too much for him and "he laid down his hammer and he died".

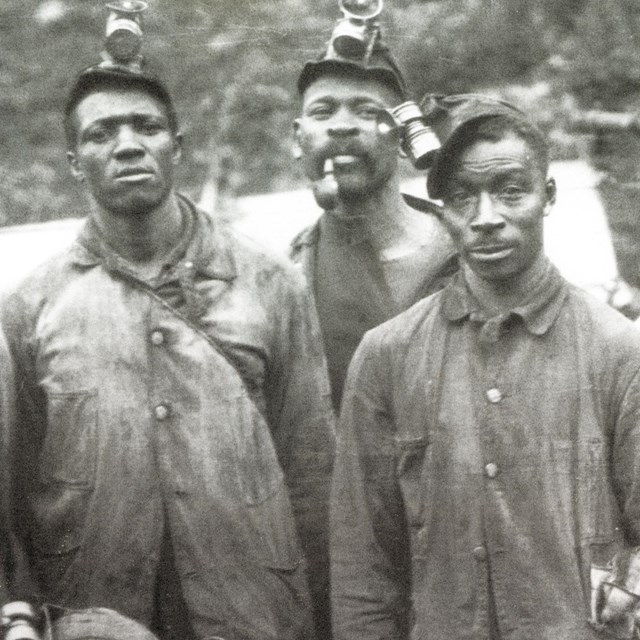

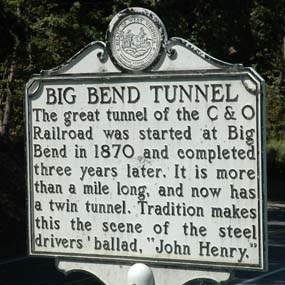

NPS The Real John HenryHistorical research supports John Henry as a real person. He was one of thousands of African-American railroad workers. John Henry's job as a steel driver was also real. These men helped drill holes for the powder used for blasting tunnels. Steel drivers swung a nine pound hammer straight and strong all day everyday. The steel bits were different lengths and sizes for different types of holes. Steel drivers were only one half of a two man team used to drill holes for tunnel construction. The other half was the shaker. The shaker's job was to hold the metal bit used to drill holes through the rock. After the hammer completed a swing, they would "shake" the bit and reposition for the next swing. Together, these teams bored through rock and mountains making paths for the railroad. The name of John Henry's shaker is unknown. Some legends call him "Little Bill" while others mention him simply as "his shaker". The contest itself is a merging of history and legend. Companies saw the new steam powered drilling machines as more efficient than men. To test the viability of the machines, they staged a contest. A steel driving team would face down the steam powered drilling machines. Whichever drilled farther the fastest would win the contest. Chosen for their skill and speed, John Henry and his shaker faced off against the steam drill and won. While most versions of the song do not list a location for this contest, some name the Great Bend Tunnel. This tunnel is on the C&O railroad near Talcott, West Virginia. Whatever version of the race you choose to believe, the result was the same. The construction of the entire C&O rail line was not a product of machinery of the industrial era. It was the physical labor of thousands of workers that built the railroad and its tunnels.

NPS / Dave Bieri LegacyHistorians believe that John Henry died at the Great Bend Tunnel. It is unlikely that he died from exhaustion after the contest, but fell victim to one of many hazards. Hundreds of workers died in rock falls and explosions. Even more suffered from "tunnel sickness" or silicosis. This disease is the result of excessive inhalation of dust from sandstone rocks. Some stories suggest that it was silicosis that took John Henry in the end. The workers who died building the tunnel now rest in unmarked graves at the tunnel's entrance. Above their graves, a statue of John Henry stands as the champion of these working men. Visitor to Talcott can see the statue standing outside the Great Bend Tunnel. John Henry was but one of thousands of men. Through their sweat, blood, and desire to build a new life, they built a foundation for the future. They brought the railroad to West Virginia and contributed to the growth of our nation. Their work still echoes in the whistle you hear today. More New River Gorge History

|

Last updated: September 14, 2023