AboutAs the whaling industry grew, the number of seamen in Bedford Village ranged from 5,000 to 10,000 — nearly equaling the population of the village! Their lives, however, vastly contrasted those of locals.

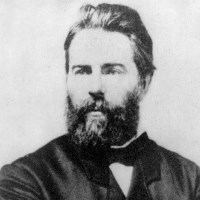

The Melville connectionWhaling was dangerous, so many seamen attended services at the Bethel prior to shipping out on whaling voyages. Herman Melville was among those so inclined.

The PulpitThe pulpit described in Moby Dick has helped make the Seamen's Chapel famous, yet it is the result of Melville’s imagination. When Melville describes the Whalemen’s Chapel, he writes that the pulpit is suggestive of the front of a ship. In 1840 however, the pulpit was not prow-shaped; it was most likely a typical New England box-style pulpit. CenotaphsThe tablets mounted on the side walls look a bit like gravestones. In a sense, that’s what they are. They are called cenotaphs, which translates to “empty grave” in Greek. Related Topics: |

Last updated: April 13, 2021