Photo courtesy of Hillsdale College About Frederick DouglassDressed as a mariner and carrying another seaman’s protection papers, Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey boarded a train in Baltimore, Maryland in September 1838. As a slave, this escape attempt was a federal crime.

Life and Work in New BedfordIn 1839, Frederick and Anna Douglass moved to 157 Elm Street, their first home located in an African American neighborhood in the West End of New Bedford. Douglass’ daughter, Rosetta Douglass Sprague, later recorded in a memoir of her mother, Anna Murray Douglass: My Mother as I Recall Her, 1900, reprint 1923: “In 1890 I was taken by my father to these rooms on Elm Street, New Bedford, Massachusetts, overlooking Buzzards Bay. This was my birthplace. Every detail as to the early housekeeping was gone over, it was indelibly impressed upon his mind, even to the hanging of a towel on a particular nail. Many of the dishes used by my mother at the time were in our Rochester home and kept as souvenirs of those first days of housekeeping.” In 1841, Douglass moved his growing family to larger quarters in the northern end of town. Their new home at 111 Ray Street (now Acushnet Avenue) was located near the wharves where Douglass often worked. “I was not long in accomplishing the job, when the dear lady put into my hand two silver half-dollars. To understand the emotion which swelled my heart as I clasped this money, realizing that I had no master who could take it from me — that it was mine — that my hands were my own, and could earn more of the precious coin, one must have been in some sense himself a slave.” Douglass also worked as a laborer on the wharves for Rodney French and George Howland. There, he had wanted to work as a caulker, making the ships water-tight. However, he encountered resistance from white caulkers. Douglass also worked at Anthony D. Richmond’s foundry.

A Sharpening Political ConsciousnessIn New Bedford, Frederick and Anna Douglass maintained their commitment to the Methodist faith. They attended several Methodist churches in New Bedford before joining the newly established African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church and became active “in the several capacities of sexton, steward, class leader, clerk and local preacher.” (Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written by Himself, 1845).

Douglass himself registered to vote less than a year after arriving in New Bedford, and the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church became his platform for articulating his beliefs about slavery and freedom. Local banker William C. Coffin heard Douglass speak, probably in 1841 when the church was located on North Second Street, and was so impressed by Douglass’ sermon that he invited Douglass to speak in Nantucket. Douglass traveled to Nantucket in August 1841, and there delivered an impassioned address that launched his career as an antislavery lecturer.

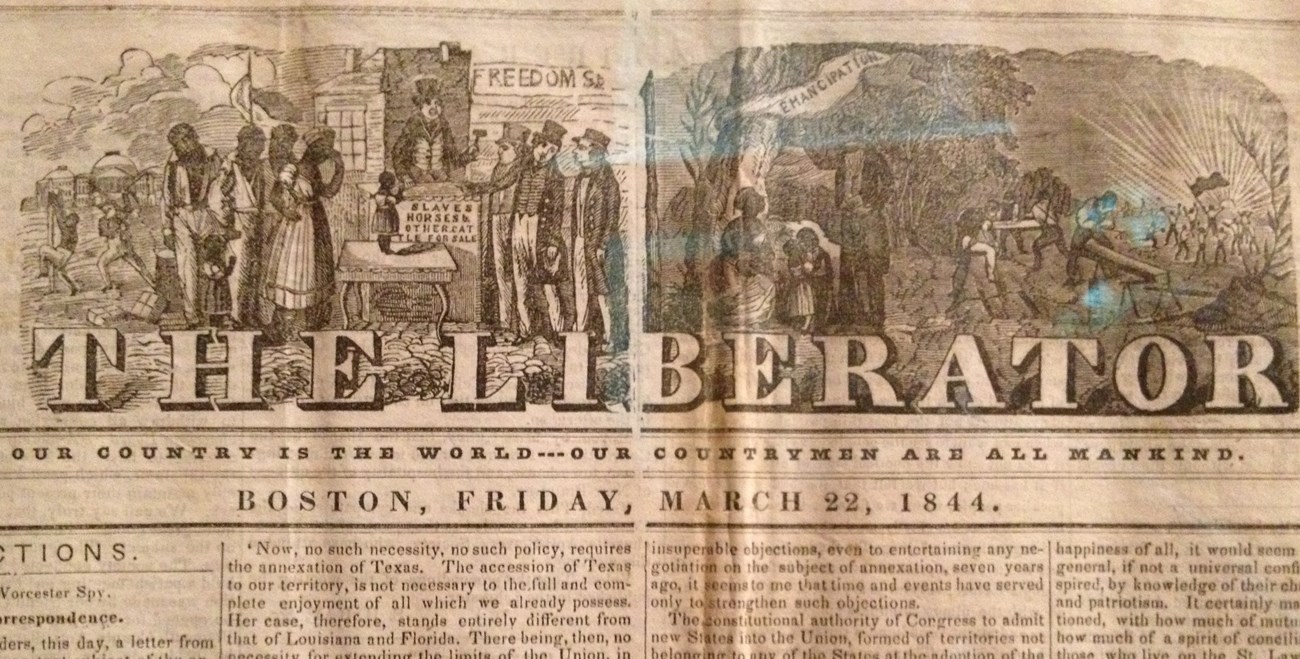

Speaking Out Against SlaveryFrederick Douglass used his personal experience to give a human face to the sufferings of slavery. He rose quickly to prominence as a favorite abolitionist and anti-slavery speaker, traveling throughout the country and world to shed light on the horrors of America’s “peculiar institution.” Douglass also worked hard for the equal treatment of all. He was one of the few men who attended the first Women’s Rights Convention in Seneca Falls, New York in 1848. He fought for black men’s right to serve in the Union Army during the Civil War, encouraging the formation of the 54th Massachusetts Regiment in 1863. He served as a political delegate in the Reconstruction South to ensure black suffrage. He spoke out frequently in support of equal employment and social opportunities, and against lynchings, discrimination, and “Jim Crow.”

Douglass' New Bedford LegacyFrederick Douglass hated slavery and dreamed of freedom from an early age. His desire to know a better world triggered his effort to learn to read and write long before he was able to escape slavery — but his exposure to a community of politically aware and active people of color in New Bedford gave life to the idea that he might himself become an effective foe of slavery and advocate for freedom. |

Last updated: June 18, 2025