Photo by Ed Goodwin

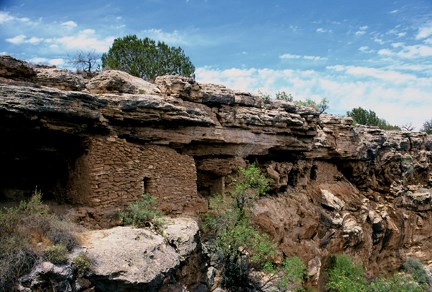

NPS Photo History of Montezuma WellThe land around Montezuma Well has been home to many prehistoric groups of people since as early as 11,000 CE. The first historical groups came to the Verde Valley after Arizona became a territory in 1863. Some accounts say Spanish settlers traveled through earlier, in the 1500s, but did not settle in the area. Montezuma Well 1864 - Present. (214 C.E., March). Meghann M. Vance.

Visit our keyboard shortcuts docs for details

NPS divers explore the depths of Montezuma Well.

The original video on the National Park Service website can be found here with Closed Captions.

The Power of WaterFor a first-time visitor, it may be hard to know what one should expect from a place called Montezuma Well. Few anticipate what will meet their eyes at the top of the first hill, just 80 yards past the ranger station. The Well is a place like no other. It shows us the power of water to affect land, life, and people. It is an oasis in a harsh desert, home to species found nowhere else. It is a peaceful pond, yet it is also the setting of a nightly struggle between life and death. It is also the ancestral home and a place of great power for the Native Americans whose forebearers lived here. Shaping LandHow could water be the most important player in a story about the desert? In an entire year, Montezuma Well receives less than 13 inches (33 cm) of rainfall—barely ⅓ of the national average for the United States. Yet the Well contains over 15 million gallons (56.8 million liters) of water! Where does it come from? How did it get there? Until 2011 the answers to these questions were a mystery. Though water may be easily turned aside, it is patient, persistent, and unrelenting. More than 10,000 years ago, the Well’s water fell as rain and snow atop the Mogollon Rim, visible to the north. Over millennia, it has percolated slowly through hundreds of yards of rock, draining drop by drop through the path of least resistance. But here the water encounters an obstacle much harder than the others through which it has flowed. Beneath the Well, a vertical wall of volcanic basalt acts like a dam, forcing water back toward the surface. In its long trip toward daylight, it eroded an underground cavern until its roof collapsed and created the sinkhole you see today. The water still flows. Every day, the Well is replenished with 1.5 million gallons (5.7 million liters) of new water. Like a bowl with a crack in its side, the water overflows through a long, narrow cave in the southeast rim to reappear on the other side at the outlet. Side trails lead from the main loop down to cool, shaded benches at each end of this subterranean waterway. Learn more about the geology of Montezuma Well.

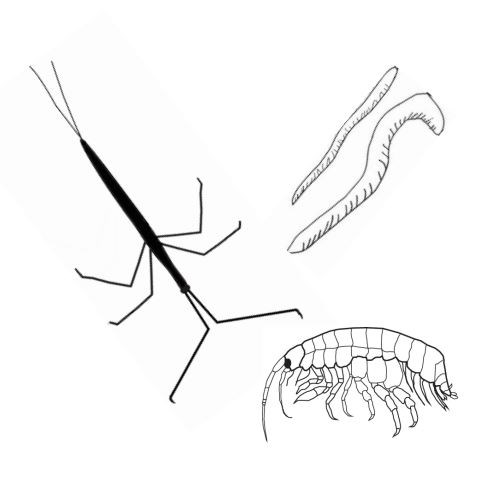

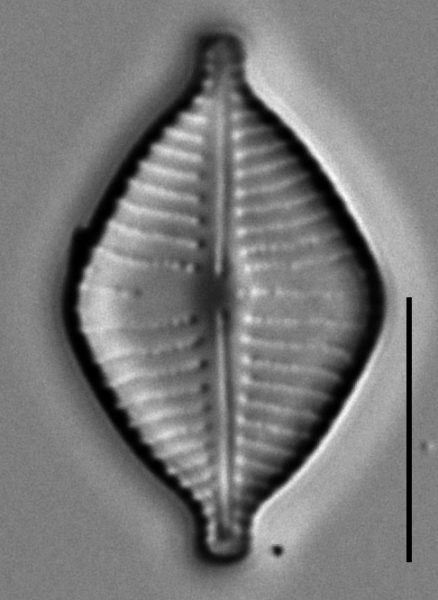

Shaping LifeIf water sculpts the land at Montezuma Well, it has also influenced life itself. All the layers of rock penetrated and eroded by this water has left a chemical signature in it. The water contains arsenic, and high amounts of carbon dioxide mean no fish can live here, as they simply cannot breathe. In the absence of fish, five species have evolved here that exist nowhere else on the planet. The waters may seem peaceful, but night after night, three of these species act out a life and death drama beneath the waves. At the center of the action is the tiny amphipod. This crustacean looks like a shrimp but is no bigger than your smallest fingernail. During the day, amphipods swim and feed near the center of the Well, just out of reach of diving ducks and other predators. At night though, while those hunters sleep, a new threat rises from below—leeches. These endemic invertebrates do not suck blood like others of their species; they eat amphipods! The amphipods flee to the surface and toward the water’s edges, only to encounter yet another predator, the water scorpion. In the pondweed surrounding the water, the amphipods must remain as still as they can to avoid detection until the sun rises again. On the sidelines, witnesses to the action, are the Montezuma Well spring snail and a unique, single-celled diatom. Shaping PeopleLike other living things, people have long found Montezuma Well to be an attractive refuge on this dry landscape. From the Well, one can see evidence of permanent settlement spanning more than 1,000 years, though people have lived here much longer than that. One of the cultures to build homes here were probably the Hohokam, here from the Salt River Valley in southern Arizona. The pithouse, dated to around 1050 CE, is exemplary of their architecture. Where the water leaves the Well and flows out of the narrow cave, these early farmers channeled it a thousand years ago into a canal that ran for miles and irrigated acres of corn, beans, and squash. The Hohokam likely lived alongside another culture who had been in the Verde Valley even longer. By the 1100s, the people of the Sinagua culture began building small dwellings in the cliffs around the Well. Over time, they built more than 30 rooms along the rim. Their pueblo here was one of 40 to 60 villages that dotted the banks of waterways throughout the valley. By 1425, the people had migrated to other places. The rooms at Montezuma Well stood empty, but the builders’ descendants still return. The Hopi, Zuni, and Yavapai all recount oral histories of their ancestors living here. The Western Apache, as well, have revered this landscape for centuries. Learn more about the different tribes the park service collaborates with.

NPS Wildlife of Montezuma WellThe water in Montezuma Well has unusually high levels of dissolved carbon dioxide and arsenic, as well as calcuim and other chemicals. This combination prevents fish from living within the Well, but is also responsible for the evolution of the five endemic (native organisms that are restricted to a certain place) species found within the Well. View a list of birds seen at Montezuma Well

NPS Photo

NPS Photo

NPS Photo Beresic-Perrins, R. K., Govedich, F. R., Banister, K., Bain, B. A., Rose, D., & Shuster, S. M. (2017). Helobdella blinni sp. n. (Hirudinida, Glossiphoniidae) a new species inhabiting Montezuma Well, Arizona, USA. ZooKeys, 661, 137–155. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.661.9728

NPS Photo

NPS Photo These tiny freshwater mollusks are found no where else in the world. They thrive on the submerged rocks and sticks in the well’s outflow called the “swallet”. These rocks and sticks have a biofilm of algae and diatoms that the snails feed on. This particular snail cannot survive outside the Well, requiring at least 50 mg per liter of carbon dioxide in the water - ten times that found in most standing waters (Blinn 2008).

NPS Photo

NPS Photo |

Last updated: December 4, 2025