|

Wolves are an important component of the predator-prey dynamics in Lake Clark National Park and Preserve and are highly sought by both park visitors and local trappers and hunters. As apex predators, wolves impact natural systems, which have adapted to and evolved in the presence of wolves. Most notably, wolves influence the abundance of ungulates, which in turn affects the structure and composition of plant communities. Recent studies using radio-collared wolves have provided knowledge and context that helps park managers understand a fully functioning ecosystem.

NPS Photo / J. Mills During a five year period park biologists captured 22 wolves from six packs in Lake Clark. Biologists collected biological samples, took physical measurements, and fit the captured wolves with GPS radio collars capable of recording locations accurate to within 100 feet. They programmed the GPS radio collars to record at least one location daily. The GPS collected data regardless of time of day or weather conditions. Combined with aerial radio tracking, this data provides tremendous insight into the daily activities of wolves. Wolves live in packs, allowing them to more safely, easily, and reliably kill prey much larger than themselves. To maintain the pack's structure, strong social bonds are needed among members. Fall wolf packs average 5.3 (range 3-7) animals per pack and typically 4 packs occupy the interior region of Lake Clark.

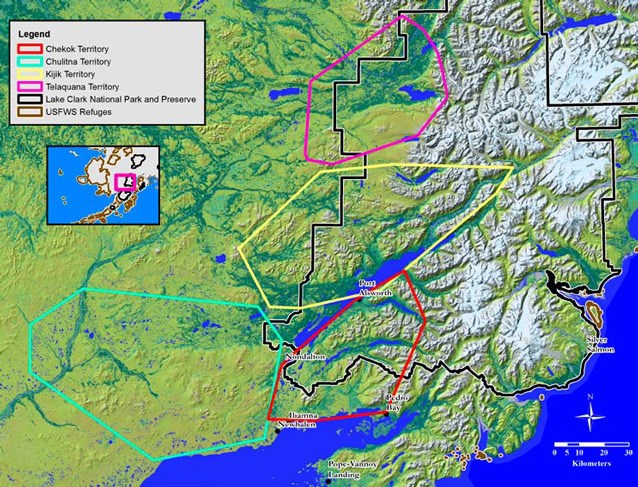

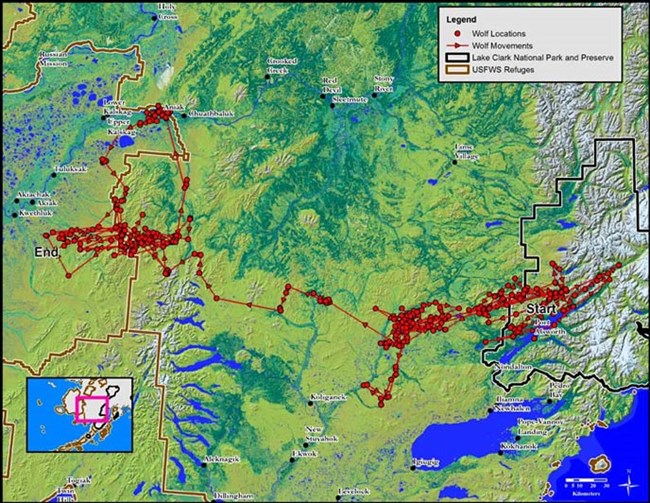

Most young adult wolves leave the pack they were born into, seeking a mate and lessening food competition among pack members. Dispersal has kept Lake Clark packs small, with wolves travelling as far as 157 miles from their original territory. Packs maintain a territory in which they den, raise pups, and hunt. These areas are dynamic, changing with season, prey distribution, and the distribution and movements of adjacent packs. Territories in Lake Clark are large, even by Alaska standards, averaging 675 square miles (range: 264 - 1259 square miles). Density of prey is one factor that affects territory size;fewer prey requires more travelling to increase the likelihood of encountering food. Moose, the primary prey of wolves, are currently at low densities throughout the interior of the park (0.37 moose/square mile). This likely contributes to the size of wolf territories in Lake Clark.

NPS Photo / A. Stanek. As a generalist carnivore, wolves hunt prey that can range from the diminutive and agile snowshoe hare to the massive moose. Regardless of the prey’s size, it’s generally the hard-won reward of extensive travelling. Radio collared wolves in Lake Clark commonly traveled distances of greater than 20 miles in 15 hours during winter while searching for vulnerable prey.

While visual observations were critical in documenting predation events, direct observation has many difficulties and limitations. The use of indirect methods of diet analysis alleviates some limitations and allows assessing diet over a broad time frame. In Lake Clark, biologists used an analysis of stable carbon and nitrogen isotopes within hair and blood components to gain additional insight into the annual diet of wolves. Many prey items are isotopically distinct and wolves fit the old adage "you are what you eat," meaning their tissues are representative of their diet. Breath, blood, hair and bone can all be used to provide data on daily diet to the compilation of diet over the life of a wolf. Analysis indicated significant diversity in diet composition among wolves in Lake Clark, especially in regards to use of salmon (range: 1-89% seasonally). While terrestrial prey is the most important component in the annual diet of Lake Clark wolves; seasonally, the diet contribution of salmon may exceed that of terrestrial prey.

Partners and Contact Information The National Park Service partnered with the following organizations during this study:

If you have any questions or would like more information on this project, please contact:

|

Last updated: December 13, 2017