NPS June 6, 1912 dawned clear and calm. Residents of the area were busy getting ready for the upcoming fishing season, but for at least a week people had felt earthquakes. Earthquakes are common in Alaska, a region long known for geologic instability, but people living and working in what would later become Katmai National Park and Preserve noticed that these earthquakes were unusually frequent and getting stronger. These earthquakes had prompted the two remaining families at Katmai Village to evacuate their homes two days earlier. They were wise to do so. Around 1 PM on June 6, the skies darkened over Katmai and for the next 60 hours the sun disappeared. The greatest eruption of the 20th century had begun.

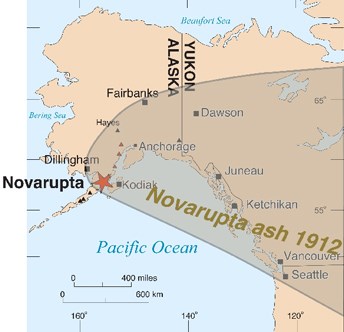

USGS/J. Fierstein Size and ImpactsThe Plinian style eruption at Novarupta on June 6-8, 1912 was the world’s largest volcanic eruption of the 20th century and one of the five largest in recorded history. No volcanic eruption since Tambora in 1815 has surpassed it. In total, 3.1 mi3 (13 km3) of magma exploded out of the earth at Novarupta. This is 30 times more magma than the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens. Ash soared to over 100,000 ft (32 km) into the atmosphere. Kodiak Island, downwind of the ash cloud, was plunged into a darkness that lasted nearly three full days and the ash cloud eventually encircled the earth. The summit of Mount Katmai, some 6 miles (10 km) distant from Novarupta collapsed as magma was drained from underneath it and vented at Novarupta. The former site of Mount Katmai’s summit is now occupied by a 1.9 mi (3 km) wide and 2000 ft (600 m) deep caldera.

Left: National Geographic Society Katmai expeditions photographs, Archives and Special Collections, Consortium Library, University of Alaska Anchorage. Right: NPS/R. Wood.

National Geographic Society Katmai expeditions photographs, Archives and Special Collections, Consortium Library, University of Alaska Anchorage. Historical SignificanceThe 1912 Novarupta-Katmai eruption left a widespread and long lasting historical legacy. Local residents of the area were forced to abandon their homes during the eruption and they never returned. You can read more about people’s direct experiences with the 1912 eruption in Witness: First Hand Accounts of the Largest Volcanic Eruption of the Twentieth Century. It also brought worldwide attention to a little known and obscure region of the Alaska Territory. Scientific expeditions funded by the National Geographic Society in the 1910s led to the creation of Katmai National Monument in 1918.

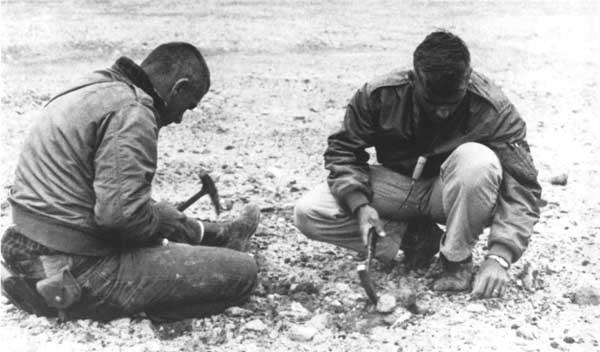

Photo courtesy of NASA NASA and the ValleyIn 1965 and 1966, Katmai’s Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes was selected as a training destination for NASA’s Apollo astronauts. The Valley was believed to be a good representation of a lunar landscape. Katmai shares several geological features with the moon, like igneous rock and ashy soil. The astronauts journeyed into Katmai and “played the moon game” in the Valley’s barren, rocky landscape. The astronauts were given limited information and dropped off in the Valley to collect geological samples and effectively communicate their findings with the geologists. The goal was to evaluate and improve communication between the scientists and astronauts. The astronauts were staying at the Brooks Lodge fishing camp while they were at Katmai, where in the evenings, they participated in discussions about geology and volcanic activity.

NPS/M. Fitz Scientific SignificanceThe 1912 Novarupta-Katmai eruption has been called one of the most provocative eruptions for volcanologists. Its great volume places it among the five largest eruptions in recorded history. Within recorded history, it was virtually unique in that it generated a large volume of pyroclastic flows that came to rest on land (Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes). Dispersal of the eruption’s ash cloud led to to pioneering work on the affect of volcanic eruptions on climate. The full story and mechanisms of the eruption are not fully understood. Still, an expansive scientific literature exists on this eruption and the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes, and it is now one of the most intensively studied eruptions in the world. The Novarupta-Katmai Eruption of 1912—Largest Eruption of the Twentieth Century: Centennial Perspectives and Alaska Park Science: Volcanoes of Katmai and the Alaska Peninsula are two great sources for more information. Valley of Ten Thousand SmokesIn 1916, a group of explorers funded by the National Geographic Society and led by botanist Robert F. Griggs penetrated the devastated region surrounding Mount Katmai. After a long and difficult hike into Katmai Pass from the Katmai River valley, Robert Griggs stumbled upon a landscape and a sight that he would never forget. Griggs later wrote,

National Geographic Society Katmai expeditions photographs, Archives and Special Collections, Consortium Library, University of Alaska Anchorage. Griggs had discovered a transformed Ukak River valley. This was a place once covered in shrubs and tundra and frequently traveled by Alutiiq people. It was changed in a matter of hours into a steaming mass of pumice and ash that Griggs named, “The Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes.” The 1912 eruption’s pyroclastic flows and surges filled the Valley with thick deposits of hot ash and pumice. Buried snow fields and glacial streams flashed into steam as well as any subsequent rain and snow melt that seeped into the pumice fields. For years after the eruption, thousands of fumaroles (volcanic steam and gas vents) shot into the sky. Griggs and his team thought the fumaroles were permanent features tied to a shallow magma chamber. In time, Griggs thought they would rival the geysers of Yellowstone National Park. So convinced of the Valley’s uniqueness and it’s scientific significance, Griggs and the National Geographic Society lobbied to protect the area. Largely because of their efforts, Katmai National Monument was created by presidential proclamation in 1918. Griggs’ account of discovery and exploration of the Valley is well documented in his 1922 book, The Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes. By the 1930s most of the fumaroles had cooled as the residual heat trapped within the pyroclastic flow and surge deposits dissipated. Today, deposits from the former fumaroles paint the surface of the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes.

NPS/M. Fitz |

Last updated: August 24, 2021