The vehicle stops at what might be best described as a “small pullout on the side of the road.” No signs, no markers at all. Just a pullout and the road rising toward Mt Griggs on the other side of the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes. I unload my backpack and gear from the car, and eye the cow parsnip warily briefly, then plunge into the overgrown, unofficial trail. The trail drops downhill steadily. It drops toward the valley of Windy Creek, splitting an unnamed range from the Buttress Range, with Mageik rising beyond. The trail passes through an immense patch of cow parsnip, then flattens out and crosses a short tundra bog.

The trail solidifies to ground that looks more similar to the Southwest than Alaska, and views open up toward Mt Juhle and Mt Griggs and the lower portion of the Valley. Surprisingly, I encounter a few other backpackers. We take in the evening light over the Valley briefly, then I continue down to Windy Creek. The crossing isn’t bad – around knee deep. But the trail becomes unclear on the other side. A few different social or bear trails – it’s hard to tell which – leads through an alder thicket to a small meadow. Climbing an embankment on the other side leads to a social trail on top that turns toward the Valley Visitor Center on the top of the ride that I just descended from. After some step retracing, eventually it becomes clear that the route does go this way, then makes a quick jog back on itself and shoots across the open terrain toward the toe of the Buttress Range and Mount Griggs beyond. Alder crossings and a few streams break up the open expanse of volcanic sediment that the trail crosses as it wraps around the west end of the Buttress Range toward the Valley proper. Running out of light, I make camp for the night and make sure that all my gear is stowed Bear Aware just in case.

The next morning, I get an early start before most dew has the chance to condense on my sleeping bag. I have a long way to get today – hopefully to the Mageik Lakes via Novarupta and Katmai Pass – so an early start is paramount. Volcanic sediment is the tread for most of the hike – at first, it’s relatively flat with some minor alder and stream crossings, but after a mile or so, the River Lethe moves closer to the range and squeezes the trail on the lower slopes of the range itself. The alders choke the drainage crossings, increasing the amount of bushwhacking, and a couple of the crossings prove rather sketchy, ascending essentially piles of ash that you can feel slide under your feet. Think about walking up sand dunes and you get the idea.

Eventually the Lethe bends away from the mountains again and the terrain starts to flatten a bit as I approach six miles, where a bowl in the side of the range appears, with a stream flowing out. Here I encounter another camper, a fisherman spending some time in the park before his flight out from King Salmon. It’s time for breakfast; I take advantage of a lone alder tree near the stream crossing to filter my water for the meal and the rest of the day, anticipating it to be pretty dry from here to Novarupta and Katmai Pass. I enjoy the panoramic view of the Valley from this spot, from which virtually all major points within it are visible. Katolinat at the base; Griggs directly north; Baked and Broken Mountains to the northeast, with Trident and the remains of Katmai beyond; Falling and Cerberus marking the entrance to Katmai Pass to the east; and Mageik to the east-southeast, with its multiple glacier-clad summits.

The trail ends here. I make my way toward Baked Mountain, looking for a safe place to cross the Lethe. To the northeast, I find it, an area where the river flattens and widens between gorge sections upstream and downstream. Stabbing the water with my trekking pole to test the murky depths, I work my way across. At the deepest it is roughly knee deep – not too bad. Typically the Lethe is best crossed early in the day due to glacial melt increasing in the afternoon, so I’m happy to be across by 10. Continuing on a line toward Baked Mountain, I cross a number of ash storms that blow down the central Valley from the direction of Katmai Pass. From a distance, it reminds me of a khamsein from my time growing up in Egypt. Khamseins are dust storms, with sand often so fine it will fit between your teeth. At a couple points, I can feel small ash particles getting into my mouth here as well, but it is not as bad as it can be today and I push through to the pass between Baked and Broken.

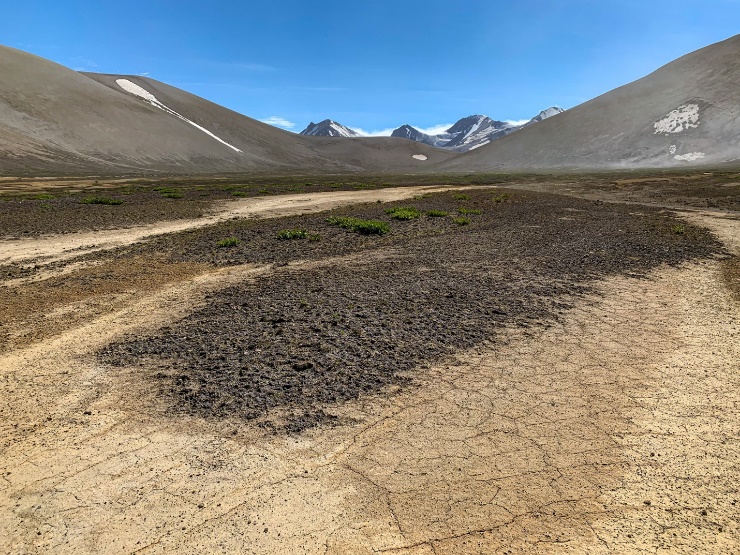

Here comes cryptobiotic soil. It’s not evident at first, but becomes so as I travel further into the valley separating the two mountains. Eventually, in an attempt to limit my impact on it, I eventually make my way to a dry wash corridor, where the occasional flow of water makes it a little harder naturally for the soil to develop and establish itself. There is still a surprising amount of vegetation around for the cataclysmic eruption that took place so close nearby and harsh climate of the Alaska Peninsula, and both the density of the soil as a percentage of ground cover and the amount of vegetation seems to be increasing relative to the lower part of the valley. As the amount of soil continues to increase, I spot a social trail traversing the flank of Baked Mountain and make my way to it in a further attempt to limit my impacts. The trail ascends to the saddle between Baked and Broken, where I can look down into the valley separating them from Trident and Fallen Mountain. Novarupta should now be visible, I think. I pull out my topo map and look around on the floor. No sign of the lava dome that I’m expecting. I check the map again and look to my left.

My jaw drops. It’s practically in front of me – only a small arm of Broken seems to separate the saddle I’m standing on from the dome - and nearly as high as the saddle but much larger than I was expecting. Suddenly the whole Valley starts to make sense.

I take in the view in both directions, and work my way down to the valley floor, crossing a number of dry washes toward Novarupta, eventually reaching the ring thrown up around the dome. I walk perhaps 40% of the way around the dome on the east side, including up to the upper end of the ring (it’s higher on the north side than on the south, one of the key factors in identifying Novarupta, not Mt Katmai, as the primary source for the eruption of June 6th, 1912). The dome is immense.

The entire landscape comes into focus now. Why there is ash and pumice at Brooks Camp and around King Salmon. Why the Valley exists. Why the fumaroles that resulted created such an impression on Robert Griggs in his post-eruption expeditions, leading him to press for the establishment of Katmai as a national park. Why President Wilson used the Antiquities Act to designate Katmai National Monument – a type of national park – in 1918. How the ash created a “year without summer,” lowering global temperatures for 1912 and 1913 by as much as 1.6 degrees F (-0.9 degrees C). In all, 3 cubic miles of magma erupted in 3 days; no eruption since 1815 has surpassed it. Some of the most famous eruptions in history, such as St Helens in 1980 and Vesuvius in AD 79, only produced 0.1 and 1 cubic mile, respectively. Even Krakatau in 1883 falls short at 2.2. The sound of the blast was heard as far away as Juneau, 750 miles distant. Seeing Novarupta, and the size of its dome, makes these more than mere statistics, and puts everything in context.

After a snack and some admiration of Trident, Katmai, and the Knife Creek Glaciers – a rare park glacier that is actually advancing since it is insulated by warming air temperatures by a layer of ash that rests on top from Novarupta – I make my way toward Katmai Pass.

Katmai Pass has a fearsome reputation. Stories of 100 mph winds strong enough to blow people off their feet and drag them along the ground. While it is not so strong today, it definitely picks up. I also encounter a marine layer that leads me to pull out my rain pants and jacket as it showers me along with the steady breeze. The layer is mostly directly in the pass at this time, but it’s also blocking any views to the east, even of Observation Mountain, which must be climbed or gone around to gain any view of the coast, so I turn around near the easternmost slope of Fallen, cross the Lethe again here near its headwaters, and turn back west, wrapping around Cerberus and exiting the pass.

As I exit, it again occurs to me just how much vegetation grows here at the upper end of the valley, and seeing the marine layer coming through it pass, it occurs to me that there may be additional moisture at this end – perhaps that combined with the rich volcanic sediments contributes to more favorable development opportunities for the cryptobiotic soil and, in turn, additional plants. Dwarf wildflowers and small grasses continue to abound at this end of the valley, regardless of the reason.

The wind howls as I wrap around the west flank of Cerberus, flapping the rain cover on my pack and my rain pants. I enter the uppermost portion of the valley, the bowl immediately west of Mageik. The lakes here are somewhat hidden by the terrain, but consulting my topo map I eventually make my way toward the foot of Mageik, although I can see a ravine with an apparent cascade on the west side of the depression, coming off the Buttress Range. I’m considering extending the day slightly to go over there for some shelter from the wind. By this point, I can see the marine layer flowing through the pass and partway down the Valley. It’s starting to obscure the view over to Novarupta and Katmai, and surely will eventually reach Baked as well.

Making my way toward to foot of Mageik, I round a corner in the terrain and gasp. A lake of a light, almost hazy sky seeming, blue comes into view. Under the now-cloudy sky, the blue glow of the glaciers on Mageik stands out nicely. Best of all, there’s a small ravine that blocks the wind and makes for an ideal camp spot for the night. Just before bedtime, a ray of sunlight splits the clouds and shines on the western summit and a portion of the glacier that descends from it. Unfortunately my camera had died earlier in the day, but a ranger friend used to say that “the best pictures you take are in your mind,” and this was one of those moments for sure.

Day three. I have most of the day to make it back about 15 miles to the trailhead. Based on my pace yesterday, a midday departure should do it (note that I am faster than average and packed light for this trip). I try and get up to the toe of one of the Mageik glaciers, but that doesn’t pan out, though it does reveal an alternate route that may work in the future, and it does get me a beautiful view down the valley with the blue lake beneath me. Having packed out, I set off down the Valley, crossing the Lethe again near its source at the other Mageik Lake, the brown lake, where it was more braided, in two channels, and about shin deep.

I make my way across the multicolored ash deposits back to the bowl marking six miles from the trailhead. The weather is better than it was yesterday afternoon, and I make good time despite the soft, ashy tread. The social trail origin is a bit harder to find returning, but watching for it on the hillside I eventually spot it and use it to return to the trailhead, stopping primarily to provide information to a couple backpackers on their way to the now mostly wind-demolished huts at Baked Mountain for the night. I recross Windy Creek and walk back to the Robert Griggs Visitor Center to meet my ride after two incredible days in the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes.