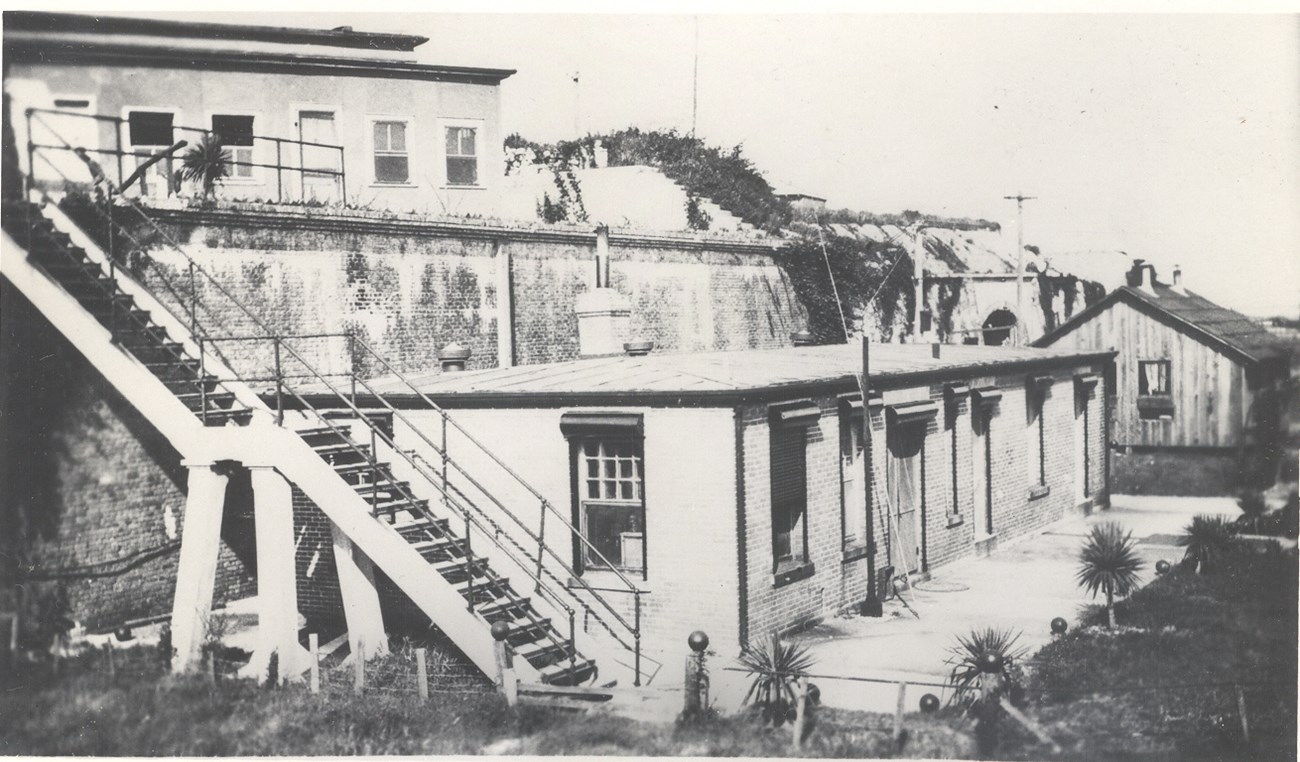

NPS Collection “The supreme value of the mine lies in its perfect adaptability to harbor defense, for which purpose it holds a position which many experts consider to be more important even than that of the high-powered breech-loading rifle.” —Scientific American, August 1905 The United States’ coastal defenses declined in the 1870s and early 1880s due to a lack of money. At the same time, changes in the design of heavy cannon and armored ships equipped with steam-driven screw propellers exposed the US to foreign attacks. In 1886, the federal government started improving its coastal defenses and the US Army’s ability to operate them. A submarine mine defense system became an important weapon for protecting the nation. The Army needed different buildings, equipment, and tools for storing and assembling mines. Each had a specific purpose. A mine storehouse, or storeroom, contained all the disassembled mine equipment. Empty mine casings sat on racks inside. An overhead trolley moved heavy equipment like casings and anchors. One or more cable tanks sat inside a separate building. Each tank, containing fresh or saltwater to prevent the cable’s deterioration, held reels with thousands of feet of cable. Powder magazines stored explosives like dynamite and gun cotton or trinitrotoluene, or TNT. To assemble mines, empty casings, cable, and explosives were sent to a mine loading building. An overhead trolley moved mines through the loading and assembling process. A small cable test tank inside ensured each mine was water-tight and the electrical circuit worked. Hand-pushed flat cars on a rail track moved equipment to each building. Assembled mines moved along the track to a mine wharf. A mine laying ship, or mine planter, then installed the mines. Cables connected a group of mines to a mine casemate. Batteries and operating boards with master switches allowed soldiers to fire individual mines. From the primary mine commander’s station, a mine commander led soldiers in firing mines. Different Army engineers planned and built Pensacola’s mine defense system. Engineers included Philip M. Price, Frederick A. Mahan, Clement A. F. Flagler, and James B. Cavanaugh. Each officer had studied at West Point. Price changed casemates inside Fort Pickens in 1894 to serve as a mine casemate.9 Mahan replaced Price and finished the job in 1895. In July 1898, Mahan began building a mine storehouse and cable tank building. Flagler, who replaced Mahan in November 1898, continued the job by converting a boarding house into a mine loading building. Each structure stood near a rail track to move the equipment. Flagler also modified the fort’s northwest cistern into an extra cable tank. Engineers replaced the first mine structures after the June 1899 explosion at Fort Pickens. Flagler built a new a mine storehouse on the original 1898 foundation and constructed a larger cable tank building on the old foundation. He completed both one year later. Cavanaugh continued the job of building a new mine loading building and mine casemate outside Fort Pickens. He finished the job in June 1907. Engineers finished the mine commander’s station on top of Fort Pickens two years later. The appearances of the mine structures hid the importance of the mine defense system. Structures varied across the nation in shape and size. Existing structures like storehouses and loading buildings look like warehouses. At a time of rapid technological changes, weapons received more attention than structures. The Army eliminated Pensacola’s mine defense system in 1926. Responsibility for the harbor’s mine system fell to the US Navy. The Army repurposed each structure for other purposes and continued using them through World War II. Submarine mines are an American invention. First called torpedoes, they first saw use during the American Revolution. Several improvements were made during the next 80 years. Mines saw widespread use by the time of the Civil War. They became more advanced in the late 1800s and early 1900s. A submarine mine defense system became the first modern armament planned for Pensacola Harbor.20 The Army classified submarine mines as primary armament, a title given to the heaviest coast defense weapons. Mines formed part of a mine command. At Pensacola, the mine command included mines, searchlights, and batteries Center, Payne, and Trueman. Mine casings were spherical, and later cylindrical, in shape. Empty casings weighed between 308–1,073 pounds. Depending on the size, mines contained 100 or 200 pounds of explosives and a firing devise. As many as 19 mines were strung together to create a mine group. One or more mine groups could be used to defend a shipping channel. The Army used different types of mines. Noncontrolled automatic, or mechanical, mines self-fired when a ship passed nearby. Controlled electrical mines fired when a soldier on shore flipped a switch, sending an electrical current through a cable to a mine. Mines were either buoyant or grounded. Buoyant mines, suspended from planting buoys and weighed down by anchors, were used in water between 20–150 feet deep. The Army first used Pensacola’s mine defense during the Spanish-American War. On April 9, 1898—16 days before Congress declared war—soldiers planted mines to defend the harbor from a Spanish naval attack. Only a mine casemate for controlling the mines existed at the time. Engineers used casemates inside Fort Pickens for a storehouse and as an engine room to power a searchlight. Forty-five mines in seven groups were planted. Soldiers even used gas tanks to make more mines. The war ended with US victory on December 10. Engineers removed the mines from the water and destroyed them. Though the Spanish navy never attacked Pensacola, the harbor’s submarine mine defense system illustrated the nation’s readiness to defend itself. Bearss, Edwin C. Historic Structure Report, Fort Pickens: Historical Data Section, 1821–1895. Denver: Denver Service Center, National Park Service, 1983. Bearss, Edwin C. Historic Structure Report and Resource Study: Pensacola Harbor Defense Project, 1890–1947. Denver: Denver Service Center, National Park Service, 1982. Berhow, Mark A., ed. American Seacoast Defenses: A Reference Guide. 3rd ed. McLean, VA: The CDSG Press, 2020. U.S. War Department. Drill Regulations for Coast Artillery, United States Army. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1909. U.S. War Department. Manual for Submarine Mining. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1912. Wiss, Janney. Historic Structures Report: Fort Pickens Mine Support Structures. Atlanta: Cultural Resources Division, Southeast Regional Office, National Park Service, 2015. |

Last updated: May 1, 2020