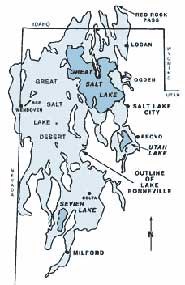

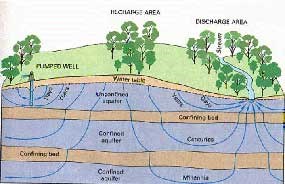

Utah.gov The Great Basin is a land defined by water, though water itself is scarce. The basin characteristic of this region means that no water in the region ever reaches an ocean, except by human intervention or by evaporation, when water molecules return to the planet-wide hydrologic cycle. In other words, any precipitation that falls in the Great Basin stays in the Great Basin. During the Pleistocene era (3 million to 10,000 years ago), water was abundant as glaciers advanced and retreated in a climate that was an average 8°F cooler than today. Lakes filled many of the basins to a depth of up to 1,000 feet. Lake Bonneville, a large pluvial lake that flooded much of the eastern Great Basin during this era, extended from the Wasatch Mountains in Utah to the Snake Range in Great Basin National Park. Additionally, the reaches of Lake Lahontan covered much of western Nevada. These aquifers are recharged from surface precipitation, typically snowmelt. In the Great Basin Desert, however, with less than 10 inches of annual precipitation, there is little to no recharge of these reservoirs. Groundwater can discharge at the surface naturally in the form of springs or seeps. Water is drawn unnaturally to the surface by the drilling of wells or by large scale groundwater pumping.

USGS Groundwater in Great Basin National ParkGreat Basin National Park is part of two Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) defined drainage areas. The east side of the mountain range is part of Hamlin-Snake Valleys (USGS cataloging unit 16020301) and the west side is part of Spring-Steptoe Valleys (USGS cataloging unit 16060008). Snake Valley is the neighboring valley to the east and Spring Valley is the neighboring valley to the west. Both are part of the Great Salt Lake flow system, with water flowing underground to towards the Great Salt Lake in Utah. The most recent research done regarding groundwater in the Great Basin National Park area was completed as part of the Basin and Range Carbonate Aquifer System Study (BARCASS) by the USGS and Desert Research Institute. |

Last updated: November 19, 2024