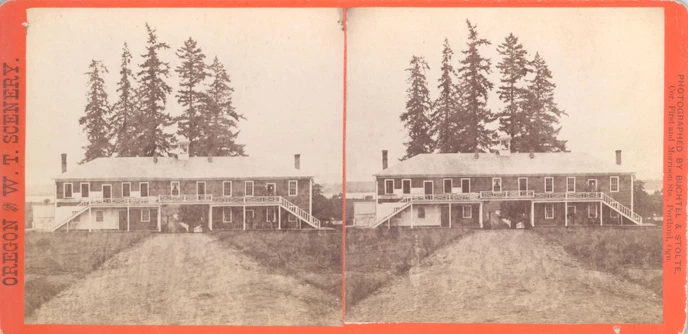

Museum Collection, Fort Vancouver National Historic Site Guard House Stereoscope "a place of punishment, void of liberty" Gregory P. Shine NOTE: This chapter is taken from the award-winning publication "Revealing Our Past: a History of Nineteenth Century Vancouver Barracks through 25 Objects" available as a free download here. If you were to guess the function of the building in this photograph, what would it be? Its long, two-story design and chimneys might suggest use as a barracks or living quarters for the post's soldiers. Its cupola, bell, and ornamented second floor railings might signify more than a run-of-the-mill operation inside, such as an office or headquarters. The open center with the roadway passing through might lend itself to a delivery or storage function, like a warehouse. The long, straight roadway, the grassy areas alongside it, and the glimpse of Columbia River to the left suggest that this building is located on a rise, just south of the barracks' parade ground. What was this building? Why was it important to photograph in the 1870s? Why is its story important today? The east side of the first floor of the building, viewable at the left of the image, provides a clue. While the white clapboard may reflect a painting project in progress, the bars on the three visible first floor windows on the building's east side reveal its purpose: the Guard House. Since the advent of the post, a guard house or jail facility has been present. Consistent with army policy at the time, original plans for the post's first buildings in 1850 show a small Guard House, along with other essentials including barracks buildings and the iconic structure today known as the Grant House. In 1878, the Army improved and expanded the Guard House. A newspaper noted that it was over one hundred feet long and included "upstairs rooms for chapel and reading room." It is from the perspective of the Grant House—the post commander's quarters for many years that an early photographer captured this image of this Guard House. In this role, it served as the place of incarceration for those soldiers who failed to abide by army rules and regulations. Directly facing the center of the post, it stood as a symbol of military authority, a constant reminder of the army's power and control. However, a stint in the guard house was not limited to recalcitrant soldiers. For decades in the nineteenth century, this building, its site and nearby grounds served as a place of imprisonment for dozens of American Indians, including those from the Nez Perce, Paiute and Shoshone nations. Soldiers could be—and were—held in arrest for any number of reasons. In addition to the Articles of War and numerous army regulations, officers expected soldiers to follow orders. "All inferiors are required to obey strictly, and to obey with alacrity and good faith, the lawful orders of the superiors appointed over them," commanded Article I of the 1861 Army Regulations. If not, a robust system of garrison and regimental courts-martial existed, complete with trial and sentencing. Possible punishments in the nineteenth century included death, confinement, confinement on a diet of bread and water, solitary confinement, hard labor, wearing of a ball and chain, forfeiture of pay and allowances, discharge from service, reprimand, and reduction in rank. "Uncle Sam ought not to expect all the cardinal virtues for eight dollars a month," one enlisted man explained to a post officer, and at Vancouver Barracks—like many other western forts—use of alcohol contributed to many incidents requiring court martial, such as insubordination and failure to pass inspection. Each month, regulations required that each army post submit a report that detailed the "prisoners in confinement" at its guard house (see image next page). Surviving reports from Vancouver Barracks, housed today at the National Archives in Washington, D.C., show that soldiers were not the only people incarcerated at the post's guard house. Several list American Indian prisoners of war. The report of April 30, 1878, under the heading "Nez Perce Indian Prisoners," notes that 23 men, 9 women, and one child "left post April 22, [18]78 en route to the Lapwai Indian Agency," after being confined at Vancouver Barracks since August 7, 1877—more than eight months and more than 400 miles from where they were found. While none of the Nez Perce are mentioned by name in this report, Nez Perce oral history remembers each of them today as members of the band of Chief Red Heart, aligned with the nontreaty Nez Perce whom the Army mobilized to force back to their designated reservation in the summer of 1877. Yellow Wolf, a Nez Perce warrior, recalled how, after the battle of Clearwater, Nez Perce scouts of Gen. Howard approached Red Heart's encampment on Weippe Prairie and encouraged him to return to the reservation. "'We will go,' answered most of those Indians," Yellow Wolf said. "There were about twenty of them, men, women, and a few children. They had not joined us. Never had been in any of the war. Coming from Montana, they had only met us there. Those Indians not joining with us in the war now bade us all goodby...." "These prisoners, as attested by every Nez Perce interviewed, were taken to Kamiah, where their horses and equipment were confiscated," wrote L.V. McWhorter, who collected dozens of firsthand accounts from the Nez Perce. "They were forced to march afoot through the blistering July heat, and dust, under guard of mounted Government Nez Perce scouts and soldiers, to Fort Lapwai, to be sent to the Vancouver Barracks as prisoners of war," McWhorter continued. Gen. Howard's official account differed considerably, stating that Red Heart's band was captured as hostile combatants, but dispatches from army officers in the field contradicted this, stating that they "came in yesterday and gave themselves up." What brought them to the post Guard House on August 7, 1877 was a military hegemony aggravated by fear, misunderstanding, politics, religion, and a desire for continued control. Also, it seems like they were simply in the wrong place at the wrong time. At Vancouver Barracks, a local newspaper reported that Red Heart's band was "confined in the Guard House until such time as it may be thought best to send them to a reservation." Shortly thereafter, it described that, adjacent to the Guard House, "[a] stockade has been built at the garrison, in which to keep the Indian prisoners. It is fifteen feet high and is built strong. In this they are kept during the day, but at night are confined in the guard house." During this imprisonment, the building itself underwent change. "The new Guard House is approaching completion, and is a handsome addition to the south side of the parade ground," a newspaper announced in February 1878. It included a small chapel area, where Christian church services were held. Although detailed information about their day-to-day activities at the Guard House has eluded researchers, on at least one occasion, the post chaplain addressed Red Heart's band in the building's chapel room. Even by military standards of the time, documents suggest that Red Heart's band lacked sufficient support for their basic health and safety. Two members, including a small son of Little Bear, died while imprisoned at Vancouver Barracks. Just prior to their release in April 1878 and their return to the Nez Perce reservation near Fort Lapwai, Howard telegraphed the post's commanding officer to "[i]ssue such clothing as may be necessary to make the prisoners of war cleanly and respectable. Any essential purchase for the women prisoners will be approved." Context gives additional symbolism to the imprisonment of Red Heart's band. Gen. Howard mentioned often that he viewed the threat of imprisoning American Indians in the post guard house as significant leverage in his councils with Yakama, Nez Perce, and other native peoples—especially those who followed the non-Christian dreamer prophet religion Howard and the prevailing American culture deemed uncivilized. Just months earlier, Howard used the threat of Vancouver's guard house to pressure a council of Nez Perce leaders. "I showed them that Skimiah, a 'Dreamer,' leader of a small band near Celilo, was already in the guardhouse at Fort Vancouver," Howard recounted, "and that this would, doubtless, be the fortune of any other 'Dreamer' leader for non-compliance with Government instructions." Days later, he described how he responded to "saucily" answered responses from Smoholla and other Nez Perce leaders. "I then show them plainly that if they persist I will have them arrested, as Skimiah was at Vancouver, and show them that if they continue turbulent and disobedient that they will be sent to the Indian country [Oklahoma Territory]." How might this policy have influenced Howard and his decision to incarcerate Red Heart's band? Howard himself may provide a clue. In the preface to his book My Life and Experiences Among Our Hostile Indians, Howard uses a later forceful imprisonment to exemplify what he found "most satisfactory" in his experience with American Indians. "To me," he wrote, "the most satisfactory operation in the Northwest was inaugurated by a very small band of savage Indians near the head waters of the Salmon river. In this campaign I did not take the field, but my trusted subordinates subdued the Indians, captured the whole tribe [Paiute and Shoshone], and brought them down the Columbia River to my headquarters, which were then near Vancouver Barracks. Here we had the opportunity of applying the processes of civilization, namely, systematic work and persistent instruction to Indian children and youth. These Indians were well fitted to abandon their tepees and blankets, dress as white men, and join the civilized Warm Spring Indians who dwelt just beyond the Dalles of the Columbia. In this work of preparation, or I may say of probation, the young Indian princess, Sarah Winnemucca,— of whom I shall have something to say in this volume, — was my interpreter, and bore a prominent and efficient part." A major goal of Howard and leading Americans in the late nineteenth century was to have the nation reflect the predominant values, beliefs, and practices of the Victorian era. Whether soldier or American Indian, rules and regulations existed and must be followed, or punishment or forced coercion would result. The newly expanded Guard House— with its barred windows, cells, and chapel—represented the threat of punishment and reeducation, and meted it out to both soldiers and American Indians. Dominating the south side of the parade ground at Vancouver Barracks, it played an important role in symbolizing the Army's power and control. No wonder, then, that the photographer chose it as his subject. |

Last updated: December 13, 2017