From the time that Europeans first landed on the Atlantic shores of North America, their eyes looked west toward the land and its resources. This brought them into direct conflict with the native inhabitants here, whom they called Indians. Many white settlers tried to make peace and coexist with the Indians, but in the end the quest for land, power, and wealth was too great and the Indians were forced to leave their homes. Indian Removal One of the proposed solutions to the “Indian problem” was to create a separate homeland or territory for the Indians. By the 1820s, Presidents Jefferson and Monroe had both proposed that the Eastern Indians should trade their ancestral lands for land west of the Mississippi. They felt that to survive, the Indians must become “civilized” and learn the ways of the white man. The southern tribes had been moving toward “civilization” for years. They had developed prosperous farming societies. The Cherokees even had a written language, and had declared themselves an independent nation with an adopted Constitution.

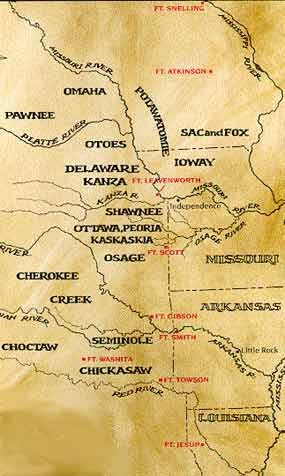

In 1829, Andrew Jackson became president. He felt the Indians did not have absolute title to the land and they could not establish an independent political sovereignty within the United States. On May 28, 1830, Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act. It authorized him to give land west of the Mississippi to Indian tribes in exchange for their holdings in the East. The United States would “forever secure and guarantee” this land to them and their “heirs or successors,” provide compensation for the improvements upon their Eastern lands, and provide assistance in their emigration to the West. President Jackson signed into law nearly 70 removal treaties. As a result, 46,000 Indians moved west and as many more were under treaty to do so. Where to Relocate The Removal Act of 1830 only addressed the removal, not exact locations or methods to be used. The Intercourse Act of 1834 attempted to control the removal and gave a location for the Indian lands, “that part of the United States west of the Mississippi, and not within the states of Missouri, Louisiana, or the Territory of Arkansas.” Due to the cultural acclimation of the Cherokee and other Southern tribes, the government tried to provide them with land acceptable to them. One incentive given was that the Indian Territory would have representation in Congress, which never came about. Nonetheless, many of the Indian tribes resisted and tribes such as the Cherokee and the Seminole had to be removed by force. The Cherokee suffered a forced march-the “Trail of Tears”- from Georgia to the Indian Territory. U.S. army estimates place the number of Cherokee who died along the route at 1,000, but of the 15,000 involved in the entire removal process, 4,000 died in either the stockades awaiting removal, along the trail itself or during the resettlement process. The Seminole tribe only complied after the U.S. Army fought two costly wars to get them out of Florida.

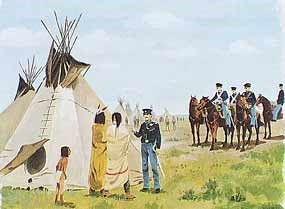

Protection of the Frontier Many of the removal treaties contained the provision that the United States would protect the relocated tribes from hostile whites and other Indians indigenous to the area. As the removed Indians began to arrive, the white settlers in Missouri and Arkansas in turn demanded protection from the relocated tribes.

This situation led to the development of a series of forts running north and south along the edge of the frontier. Colonel Zachary Taylor favored temporary posts, General Winfield Scott favored building a few large posts and Secretary of War John Bell wanted more numerous small forts. A compromise was reached and a combination of large and small forts were manned, from Fort Snelling in Minnesota to Fort Jesup in Louisiana. Fort Scott fell right about in the middle of this line of forts. The purpose of Fort Scott’s establishment was twofold. One was to maintain peace between the Indian tribes and the white settlers by providing a military presence along the military road between Osage land and the state of Missouri. The other reason was to keep peace between the various Indian tribes. Permanent Land Lost By the 1840s, most of the removal treaties had been implemented. But now westward expansion was accelerating and settlers and traders were moving across the Indians’ land, first to Santa Fe, then to Oregon. The concept of “Manifest Destiny,” control of land from shore to shore, led the United States to acquire the southwestern lands from Texas to California, and the Oregon Territory. With the discovery of gold in 1848, thousands of people streamed through Indian Territory. By the 1850s, these factors, along with the desire for a transcontinental railroad and the establishment of Kansas as a territory, caused many of the forts of the “Permanent Indian Territory” to be abandoned. As white settlers moved into this land, the government’s policy of providing a large, permanent, and secure home for the Indian tribes died.

Visit our keyboard shortcuts docs for details

Permanent Indian Frontier and Westward Expansion: This video segment comes from the film, "Fort Scott Movie-Dreams and Dilemmas." |

Last updated: August 6, 2024