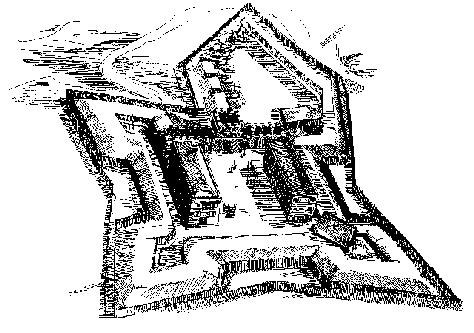

18th century drawing, artist unknown. "The fortress was regular and beautiful, constructed chiefly with brick, and was the largest, most regular, and perhaps most costly of any in North America, of British construction: it is now in ruins, yet occupied by a small garrison; the ruins also of the town only remain; peach trees, figs, pomegranates, and other shrubs grow out of the ruinous walls of former spacious and expensive buildings, not only in the town, but at a distance in various parts of the island; yet there are a few neat houses in good repair, and inhabited: it seems now recovering again, owing to the public and liberal spirit and exertions of J. Spalding, esq., who is the president of the island, and engaging in very extensive mercantile concerns."

Initially, the purpose of the Georgia colony was not so ambitious. Its founders, General Oglethorpe and twenty other trustees saw it as a social experiment, a humanitarian mission to relieve unemployment and relief to those who crowded England's squalid debtors prisons. This altruistic goal eventually expanded to include the more pragmatic purposes of expanding trade for the mother country and providing a buffer colony on the southern frontier.

The original goal of General Oglethorpe and the other trustees to relieve the suffering of those in debtors prisons remains a powerful myth even today, but despite these good intentions, the reality was far different. History records only eleven families fitting the description of debtors that eventually settled in Georgia during its early history. Even as the trustees began their work of establishing Georgia, they realized that the new colony required people with specific skills and recruited settlers accordingly. At Fort Frederica, this meant people who could provide products or services of use to the soldiers of the garrison.

The first settlers in Georgia arrived in 1733. Sailing up the Savannah River, they established a settlement on a defensible bluff that General Oglethorpe selected for that reason. He would spend the next ten years working to make the colony succeed. One of Gen. Oglethorpe's primary concerns involved Georgia's defense. The colony lay in an area between South Carolina and Florida, "debatable" land that was claimed by both Great Britain and Spain. The Spanish claim predated Britain's by more than a century and a half and at one point, Spain occupied a number of missions along the Georgia coast. These, it eventually withdrew, providing Britain with a window of opportunity to fill the vacuum. Nevertheless, General Oglethorpe did not trust Spain which had denounced the new colony of its border with Florida and knew that his venture would not go unchallenged.

To forestall any Spanish attempt to regain the Georgia land, General Oglethorpe pushed south from Savannah. Exploring the coast, he selected St. Simons Island for a new fortification. The site, sixty miles south of Savannah, would become the military headquarters for the new colony. Here, in 1736, he established Fort Frederica, named for the Prince of Wales, Frederick Louis (1702-1754). (The feminine spelling was added to distinguish it from another fort with the same name.)

Fort Frederica combined both a military installation, a fort, with a settlement, the town of Frederica. Due to the Spanish threat only seventy-five miles away, General Oglethorpe took measures to fortify both, surrounding the entire forty- acre area with an outer wall. This consisted of an earthen wall called a rampart that gave protection to soldiers from enemy shot and shell, a dry moat and two ten-foot tall wooden palisades. The wall measure one mile in circumference. Contained within this outer defense perimeter was a stronger fort that guarded Frederica's water approaches. Designed in the traditional European pattern of the period, the fort included three bastions, a projecting spur battery now washed away, two storehouses, a guardhouse, and a stockade. The entire structure was surrounded in a manner similar to the town by earthen walls and cedar posts approximately ten feet high. The fort's location on a bend in the Frederica River allowed it to control approaches by enemy ships.

Although little remains to remind us of its prowess today, a visitor in 1745 described it as "a pretty strong fort of tabby, which has several 18 pounders mounted on a ravelin (triangular embankment) mounted in its front, and commands the river both upwards and downwards. It is surrounded by a quadrangular rampart, with four bastions of earth well stocked and turned, and a palisade ditch."

Frederica town followed the traditional pattern of an English village. Similar in style if not in scale to Williamsburg, VA., its lots were laid out in two wards separated by a central roadway called Broad St. Each house occupied a lot sixty by ninety feet. Lots had room for gardens and settlers were given additional acreage elsewhere on the island for growing crops.

The first shelters at Frederica were called palmetto bowers. These involved wooden branches covered with palmetto leaves which while lacking amenities of a more permanent structure proved adequate for providing shelter from the sun and rain. In time, many settlers replaced their bowers with more substantial structures than these, but nothing more than foundations remain today. Frederica was never intended to be self- sufficient. Even before the settlers left England, the trustees had provided that adequate stores be furnished for their needs. These were distributed to the towns people on a regular basis.

Nevertheless, the settlers were also not expected to remain idle. General Oglethorpe had banned slavery from the colony for that very reason. Although the trustees' involvement was purely philanthropic, it was expected that the colonists would prosper by producing wine, silk, or some other commodity. General Oglethorpe imported 5,000 mulberry trees to try an encourage silk production, but at no success. As an economic venture, Frederica failed as well as Georgia.

In other ways, though, Frederica did succeed. As a military bastion, the fort served as a clear reminder of British power in the region. Nor was it alone it this purpose. In addition to Fort Frederica, there were four other British outposts located farther south. One of these was Fort St. Simons, located on the south end of St. Simons Island, where the lighthouse currently stands. It guarded the entrance into Jekyll Sound that provided access to Frederica's back door. Other forts were located at the north and south ends of Cumberland Island and on the St. Johns River in Florida.

Lacking sufficient numbers of soldiers, General Oglethorpe returned to England in 1737 to raise a regiment of redcoats. He was given the 42nd Regiment of Foote, now known as "Oglethorpe's Regiment," consisting of 250 men from Gibraltar, 300 men recruited in England, and 45 men from the tower of London. These combined with the soldiers already in Georgia placed nearly 1,000 men under his command. Returning from England, the regiment fell in for the first time on September 28, 1738.

General Oglethorpe's foresight proved fortunate. A year after the regiment arrived at Fort Frederica, Great Britain declared war on Spain. This started a nine-year struggle known in Europe as the War of the Austrian Succession, and America as King George's War. In the southeast, General Oglethorpe made the first move and launched an attack against St. Augustine. Although equipped with sufficient men and supplies, General Oglethorpe's siege failed and the impregnable Castillo de San Marco remained in Spanish control. The British forces retreated northward, but General Oglethorpe understood that whatever respite they had gained would be temporary.

The Spanish response came two years later. A fleet with thirty-six ships and 2,000 soldiers sailed from St. Augustine and arrived off St. Simons Island early in July. The ships forced a passage of Jekyll sound, following a lengthy cannonade with Fort St. Simons. Little damage was done to the Spanish fleet and the soldiers landed unopposed at Gascoigne Bluff, near where the causeway is today. There, they proceeded to march overland and capture Fort St. Simons without further resistance. The British garrison there evacuated before the Spanish soldiers arrived and retreated north to Fort Frederica.

Despite his initial success, the Spanish commander, Manuel de Montiano, proceeded captiously. He sent a reconnaissance in force of 200 men up the Military Road in the direction of Fort Frederica. Before they arrived outside the gates of the town, General Oglethorpe took the offensive. He sent a column of his own troops out to meet the Spanish in the wooded thickets east of Frederica. At a spot where the road crossed a sluggish stream named Gully Hole Creek, the British sprung their trap, firing a volley of bullets into the lead group of Spanish troops. Caught off guard, the Spanish recoiled in shock and confusion, retreating back toward their compatriots at Fort St. Simons.

The British followed up their victory by pursuing the Spanish. Montiano sent reinforcement to help the first column of soldiers, but these too were caught unawares and ambushed at Bloody Marsh. A regular engagement ensued, lasting about one hour, before the Spanish broke off contact and retreated again. Unsure of the terrain or how many enemy soldiers he faced, Montaino reembarked his forces, set sail, and returned to Florida. Never again would the tread of the Spanish boot break the stillness of Georgia's oak and pine forests.

By 1743, nearly 1,000 people lived at Frederica. The town enjoyed a relative measure of prosperity owing to the crown's dispensation, but it was a prosperity that was built on military outlays. For Frederica, the peace treaty that Great Britain and Spain signed in 1748 sounded its death knell. No longer needed to guard against Spanish attack, the garrison was withdrawn and disbanded.

The effect was similar to base closings today. The local economy collapsed and as many as half the town's people left to seek their fortunes elsewhere. Those that remained continued to call Frederica home until 1758. In that year, a fire started and before the last flame died out what remained of the town was a blackened, charred ruin. Nature finished the process of reclaiming Frederica with vines overgrowing the few tabby ruins still standing and in time little was left but a memory. Interest revived in Fort Frederica in the 1900s. Local residents took a lead in preserving the site as a reminder of America's colonial past. In 1945, Fort Frederica National Monument was established. Archaeological excavations were done in time that uncovered Frederica's past and allowed its story to be told again to new generations of Americans. Although it failed as a settlement, its success in defending Georgia from Spanish attack made its success as first as a British colony and later as part of the United States possible.

Author: Steve Moore, Park Ranger, Ft .Frederica National Monument,1997

|

Last updated: September 1, 2016