NPS/SIP: Mariah Slovacek

NPS*

The Pikes Peak batholith was massive. Its remnants extend from Florissant to Colorado Springs and north toward Denver. Although Pikes Peak itself is not a volcano, the Pikes Peak Granite holds evidence of a possible caldera eruption near Lake George, Colorado, 1.08 billion years ago. Since then, many different volcanic events have occurred through Colorado.

Left image

Right image

Onion-Skin WeatheringThe Pikes Peak Granite often forms rounded and even dome-shaped structures as it erodes. This is due to three main factors: the release of pressure as the rock comes to the surface, ice, and water.

NPS/GIP: Mariah Slovacek

NPS/GIP: Mariah Slovacek

show process of chemical formation of clay and freeze-thaw within cracks. NPS/GIP: Mariah Slovacek

exfoliation of rock sheets weakened by water and ice. NPS/GIP: Mariah Slovacek

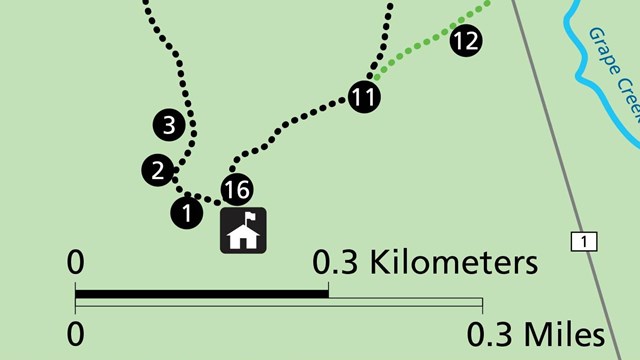

Stop 12: Mammoth Change

Click here to go to Stop 12.

Virtual Tour Homepage

Explanation of the virtual tour and links to all stops.

Stop 14: Remnants of Powerful Forces

Click here to go to Stop 14. |

Last updated: December 8, 2021