Gender, Age, & Work Roles

Throughout the 18th century enslaved people in the Chesapeake worked mostly in agriculture raising cash crops of tobacco, corn and other grains. They also raised livestock and subsistence crops for themselves and the slave owners. Enslaved people lived and worked as domestics and personal servants on plantations and in the town homes of wealthy Chesapeake landowners. Others were laborers and watermen moving, storing and shipping commodities. By the middle of the century, increasing numbers of African and native-born African American men and women were skilled laborers.

Enslaved people worked in small work gangs on plantations and their outlying quarters, in places like Carter’s Grove in Virginia or Oxon Hill Plantation in Prince George’s County, Maryland and on small farms throughout the Chesapeake. On small farms, the farmer and his family worked along side enslaved people in the fields and in domestic tasks. On the larger plantations, the planter, his sons, and mostly white indentured servants supervised African men, or “crop negroes” as some called them, working on outlying quarters of the plantation. African men supervised the work on some quarters.

Enslaved people worked as industrial workers in iron forges and furnaces, lead mines, shipbuilding and other early industries. The state purchased and hired enslaved industrial workers from private slave owners. It was a common practice of slave owners, in the second half of the century, to hire out enslaved people as industrial workers, farm laborers and as artisans (Kulikoff 1986; Walsh 1997: 194–195; Yentsch 1994:173–174).

Everybody worked. Enslaved children began to work between the ages of seven and ten. Enslaved women worked, even when they were pregnant, or were nursing their babies. Those that lived to be elderly had work assignments commensurate with their physical capabilities. Probate inventories assigned a monetary value to each enslaved person listed in an inventory under the heading “Negroes” or “Negro Chattel”: or simply “Slaves.” The inventory assigned value to an individual based upon their work capabilities and the length of time they would continue as a worker. A review of 100 probate inventories from the last quarter of the 18th century in Maryland and Virginia found very few enslaved people assigned no value (Brown, 2004a). The inventory of Thomas Addison’s estate, for example, assigned no monetary value to “Sarah Superannuated” and listed one man as “Jimmy an Idiot old & of no Value.” Sarah and Jimmy’s devaluation suggests that the Addison inventory assignment of £5 value each to “Hercules age 88,” “Stephany age 78”: and “Clara age 68” indicates these elderly people performed some tasks (Thomas Addison 1775, Gunston Probate Inventories).

The kind of work enslaved people performed, where they worked and the conditions of the degree of their labor fostered or constrained their acculturation. Over time, their work patterns contributed to enslaved people gaining varying degrees of social autonomy and economic independence, and to their cultural production of a sense of community that transcended kin relationships.

Women’s Work

The old adage, “man’s work is from sun to sun but women’s work is never done”…certainly describes the toiling of almost all colonial women especially those enslaved.

African women immigrants to the Chesapeake came from areas of West and West Central Africa where men traditionally cleared the fields for cultivation but women were the primary agriculturists. Their work roles did not change much in colonial Chesapeake. Most of them labored in the fields.

A few enslaved women worked as domestics both on plantations and in planter’s urban homes. Women domestics washed and ironed cloths, cooked, waited on the English, cared for their sick, the elderly and children. Some women were “wet” nurses, suckling the English women’s babies (Savitt, 2002).

As the size of the American-born enslaved population grew, many planters had “surplus” labor, that is enslaved people whose labor was not needed for plantation work. Wealthy farmers hired out such people, particularly women and children, to work for others. Estate managers for widows and orphans also frequently hired out the labor of enslaved women who were part of the estate. The owners of the enslaved women lived off of the income received from their labor. As hired hands, the women worked in fields and as domestics. Although enslaved men’s labor was for hire, the women were hired out more frequently (Hughes 1978:268–272; Gunderson 1986:367–368).

By mid 18th century, some African American women engaged more in skilled labor, mostly on the largest plantations. Women were taught to spin, weave, and to become seamstresses. A smaller number of women performed skilled labor as plow-women, coopers and semi-skilled laborers in ironworks (Kulikoff 1986:401; Libby 1992). Read more about enslaved women’s work in the Chesapeake.

For the pioneer generation of African women working in the agricultural labor force, traditional women’s roles in their homelands, may have reinforced a continuing sense of African identity among them. For their “native-born” daughters and subsequent generations of enslaved women, performing domestic work, learning artisan skills, and working for hire, at the very least promoted their acculturation and seems to have contributed to production of a culture of resistance among some of them. Read more about culture change associated with enslaved peoples’ work roles later in this section.

Men’s Work

Tobacco cultivation was the work of hundreds, if not thousands, of enslaved African and African American people who lived, worked and died as “crop negroes” on Chesapeake farms and plantations in the 18th century. Most of these laborers were men.

The majority of Africans destined for slavery in Virginia, arrived between June and August, when the tobacco plants had already been moved from the seedbeds, and were growing rapidly in the fields. Many enslaved African men, women, and children brought skills with them, including experience in agriculture techniques similar to those used in tobacco cultivation. Their first task on Chesapeake plantations was to weed between the rows of tobacco plants, using their hands, axes, or hoes. After a few months, they were taught how to harvest the tobacco (Calhoun 2000).

On some large tobacco plantations, “crop negroes” worked in gangs, organized by their strength and abilities. However, Landon Carter organized “crop negroes” by their productivity. Carter described the organization of his work gangs and the level of productivity he expected of individual hands:

“Therefore, by dividing every gang into good, Middling, and indifferent hands, one person out of each is to be watched for 1 day's work, and all of the same division must be kept to his proportion. And I can truely [sic]…say that I never found 20,000 [plants] per hand of corn and tobacco too much to be tended except in very wet years.” (Greene, ed., The Diary of Colonel Landon Carter…as cited in Calhoun 2004).

According to the Carter Diaries, all of Landon Carter’s enslaved laborers who were “‘well or could move,’ spent one night hanging ‘a prodigious cutting of tobacco in Scaffolds’ and another night ‘the people stemmed tobacco till the moon went down (Greene, ed., The Diary of Colonel Landon Carter…as cited in Morgan 1998:168).’” There was no break in the intensity of the labor from May to September. Most of this work was done with axes and hoes All of the planting, replanting, weeding, harvesting, and marketing was done by the hands of women, teenagers of both sexes and men. The peak productivity of men was between the ages of twenty and thirty-five. Women were counted as three quarters of a hand in the fields because their work productivity was less than that of a man (Kulikoff 1986:408).

After 1740, the increasing size of the African American workforce resulted in greater opportunities for men to become drivers, foremen, and overseers of quarters. The expanding tobacco driven economy not only changed the organization of labor but also opened possibilities of new work roles for men (Kulikoff 1986:396–408; Libby 1992). Enslaved men had opportunities to learn artisan skills that were formerly the work of indentured servants and free whites. A few men were trained as house servants, valets and livery men.

By 1770, Richard Henry Lee would write his brother William concerning the slaves at Green Spring that:

“‘Out of the 164 slaves…but 59 are crop negroes, I mean exclusive of boys, — 12 are house servants, 4 Carpenters 1 Wheelwright, 2 Shoe makers, 3 Gardeners and Ostlers…(Ballaugh 1914).’”

As Kulikoff notes, in the same year, George Mason’s father had among his enslaved men and women, “‘carpenters, coopers, sawyers, blacksmiths, tanners, curriers, shoemakers, spinners, weavers, knitters and even a distiller (1986:401).’” Other enslaved men were skilled fishermen and sailors plying the Virginia rivers and Chesapeake Bay; stevedores and carters moving agricultural products and other goods over land.

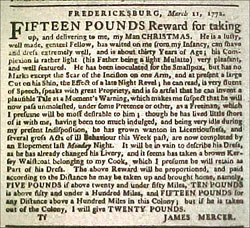

During this period, slave owners hired out enslaved artisans and tradesmen and some enslaved African Americans even managed to hire themselves out. This was one means of making money to buy themselves and their families out of slavery. The large free African American population of the Chesapeake in the first census of the United States was one of the outcomes of these developments. Read more about enslaved men’s work in the Chesapeake.

Ironworkers

Between 1716 and 1733, the Chesapeake Region saw the birth of the first southern ironworks. By 1775, the American colonies were the world’s third largest producer of iron. The industry was built largely on slave labor. There was at least 65 ironworks in the region, and according to Lewis, there are probably others that were erected and abandoned without leaving any trace. Slavery played a critical role in development of the industry. By the 1750s, enslaved men performed most of the skilled and manual labor. Forges and furnaces employed between thirty and fifty slaves (Lewis 1974).

Africans and African American laborers with iron working skills were frequently sold as a group. The Virginia Gazette May 14, 1767 advertising a forge for sale specified the workers were:

“slaves used to work there as finers, hammersmen, colliers, and acquainted with the business and two valuable blacksmiths (Jernegan 1920).”

Iron workers formed an elite group in North America reinforcing the elite group traditions related to iron working skills in West and West Central Africa that still exists in the present (de Barrios 2000:148; Barnes and Ben-Amos 1989). Toward the end of the 18th century a relatively small number of West Africans skilled in working with iron were imported to work as industrial slaves at the Catoctin furnace and forges near Frederick, Maryland. Others were imported to be blacksmiths on plantations and farms.

The first revolutionary governor of Maryland, Thomas Johnson, and his three brothers built the Catoctin furnace and forges in 1774. In creating the furnace, they defied British colonial laws. The furnace soon became a supplier of ammunition for the American Revolutionary Army (Wehrle 2002). African American production of ammunition and other iron products at Catoctin and the 65 odd ironworks throughout the Chesapeake was a major contribution to the Revolutionary War. Read more about African and African American ironworkers.

Children’s Work

Enslaved children also worked. “Old Dick” describing work when he was a child on an Anne Arundel farm said: “I was put to work on the hoe, I was up an hour before sun and worked naked til after dark (Davis 1803:378 as cited in Yentsch 1994:177).” Children who lived on rural plantations began to work around age seven. They scared birds away from the crops, thinned corn, weeded potato patches, fed the hens and carried water.

Planters often bought African American children for training in specific domestic work or artisan skills. In the kitchen, boys or girls might begin by learning to set a table, later graduating to waiting tables. The English also raised girls to be their children’s nursemaids. Like this young girl nursemaid to Governor Spotswood’s grandchildren.

From the 1720s onward, one finds enslaved female infants and children, often mulattos, being raised to be house servants, spinners, weavers and trained for other household work. Bacon-Burwell records demonstrate that Chesapeake slave owners adopted a color-base social and occupational hierarchy among their workforces. They chose mulatto women and girls, like Kate, as domestics and selected mostly mulatto men as craft persons (Walsh 1997:37).

Young boys learned to be carpenters, coopers, sawyers, and blacksmiths, often from their fathers. Slave owners trained boys from infancy to be valets and livery men, as this slave sale advertisement testifies:

“Nov. 29, 1776. THE subscriber has for Sale, a likely young Negro Man, who has been bred from his Infancy as a waiting and riding Servant, is remarkably careful of Horses (Coon 2004).”

Other enslaved children were “given” to the planters children to be their companion and personal servant for life. One 18th century traveler describes the custom of giving enslaved children to English children:

“‘When a negro-woman’s child attained the age of three years,’…wrote Mrs. Anne Grant, in her memoirs, …‘the first New Year’s day after, it was solemnly presented to a son or daughter, or other relative of the family, who was of the same sex with the child presented. The child to whom the young negro was given immediately presented it with some piece of money and a pair of shoes; from that day the strongest attachment subsisted between the domestic and the destined owner (Burnaby et. al. 1916:400).’”

The enslaved child and the person to whom they were “given” grew up together and barring some economic calamity that would cause the slave to be sold, would live their entire lives together. Enslaved children growing up under these circumstances and those raised as domestic servants had a greater possibility of learning to read, write, and to become articulate in English, skills that later many used to seek freedom.

In Africans in the Low Country, the next module section, read more about how different work roles and the organization of work influenced enslaved peoples’ cultural and counter-cultural resistance, culture change, and their production of African American culture.