Africans in the Chesapeake

Time, Space & People

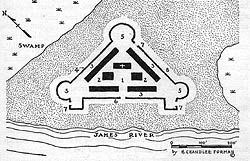

The English failed in their first attempt to establish a colony in 1585 on Roanoke Island, one of the barrier islands off what would become North Carolina. They left little more than terrain named Virginia for the virgin Queen Elizabeth the First. Twenty odd years later, in 1607 they successfully established a settlement they called Jamestown further north along the Atlantic coast at the confluence of the James River and the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay.

The Powhatan Confederacy of American Indians populated the land surrounding the Chesapeake and from the start, the Indians resisted the invading colonists. As time went on some Indians made friendly gestures to the settlers such as trading foods and introducing the English to tobacco. While the English offered the Indians friendship, they also brought them decimating diseases, occupied their territory, and sought to enslave or kill them. There was a short period of peace after Pocahontas, Powhatan’s daughter, and John Rolfe married. Peace broke down into hostilities after she and her father Powhatan died three years later. When the Africans arrived in 1619, the colony was still under intermittent Indian attacks.

The English found the Chesapeake Bay surrounded by low-lying land covered with forests and thick undergrowth. Winding streams emptied into rivers flowing into the waters of the bay that was plentiful with seafood. Around the bay were shallow tide-washed shores. Natural waterways made travel less arduous. The weather was mild. Normally, frequent, heavy rains cooled the heat of the long four or five months of summer. Unfortunately, the colonist landed in the time of a drought that lasted from 1606–1612. Without rain, the rich soil that promised productive subsistence and cash crops was not forthcoming and the settlers soon experienced famine.

Winter was cold with snow and ice, but short, lasting little more than two months. Except for the last nippy month of fall and the cold winters, the Chesapeake climate would prove to be more familiar to Africans than to the English.

The Peopling of Virginia Colony

The pressing need for laborers shaped the Virginia Colony from the very beginning. According to the Documentary History of Jamestown Island, more than half of the first 104 Jamestown colonists were gentlemen, scholars, artisans, and tradesmen. There were no laborers or sturdy yeomen farmers among the original settlers, people whose basic skills and physical conditioning would have been invaluable in creating a foothold in the wilderness. The 1609 contingent of 659 colonists included 21 peers, 96 knights, 11 doctors and ministers, etc., captains, 28 esquires, 58 gentlemen, 110 merchants, 282 citizens, and others not classified. Less than 50% were persons available for physical labor required to sustain and develop the colony (McCartney 2000 Vol. I: 15–17).

In the twelve years following their arrival, the first groups of colonists endured periods of starvation between the arrival of supply ships that also brought more colonists. Most of the new arrivals were still artisans and tradesmen. Relatively few came as indentured laborers to work off the cost of their passage to the colony. Labor continued to be in short supply (Hatch 1949).

Given the Virginia climate and rich soil, by 1614 even inexperienced colonists managed to meet their subsistence needs growing corn, other food crops, and raising cattle. They also had established tobacco as a cash crop. Yet, in spite of over 1000 new arrivals of colonists over the years, war with the Indians, disease, and famine constantly depleted the population. Colonists died of “bloody flux, burning fevers, and swellings, wheras others died of wounds they received from the Indians…for the most part they died of mere famine (Percy 1922 as cited in McCartney 2000 Vo. I:18).” Thus, laborers and food were still in short supply on April 19 of that year; Virginia’s new Governor Sir George Yeardley arrived at Jamestown. The 400 colonists who made up the population were stretched thinly across eight settlements and Yeardley found only 10–12 houses in Jamestown proper, a “timber” Anglican Church about 50 feet long by 20 feet wide and no coastal fortifications. Yeardley came with a lengthy set of instructions, plus the Virginia Company’s so called “Great Charter ” that laid the groundwork for establishing local representative government and, from the perspective of indentured laborers and the soon to arrive Africans, the precedents for making private land ownership possible though the head-right system. Under the head-right system, anyone who underwrote the cost of another person’s transportation to the colony became eligible for a 50-acre grant of the Virginia Company’s land. By importing hired workers, who agreed to work a certain number of years of labor, i.e. indentured their labor, in return for transportation to Virginia; a colonist could gain or increase their land ownership (McCartney 2000 Vol. I: 15–17). Learn more about the peopling of Virginia Colony.

The First Africans in Jamestown

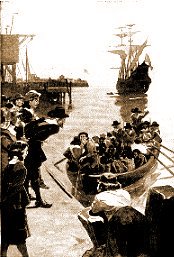

“About the last of August [1619] came a Dutch man of warrre that sold us twenty negars.” So history recorded the arrival of the first Africans to an English colony in Jamestown, Virginia. The Africans arrival would not only change the course of Virginia history but the course of what would become the United States of America. There were both men and women in this first group of Africans. Three or four days later, a second ship arrived. One additional African woman disembarked in Virginia. (Travels and Works of Captain John Smith [1910] 1967:541 as cited in Russell [1913] 1969:22 ftn.21).

The first Africans to arrive in Jamestown were welcome additions to the labor force. They were needed for the tasks of opening the wilderness, clearing land, and building settlements around the Chesapeake Bay. The first Africans, as few as they were, fulfilled a sorely needed and relatively empty labor niche in Virginia society. They and the African immigrants that followed also served another equally important purpose. Under the head-right system, they enabled the growth of a new landowning middle class located socially between the gentleman who had been granted the Virginia Company land by the Crown and the laboring class of indentured servants and slaves.

Nine months after the arrival of the first Africans, the Census of March 1620 listed 892 English colonists living in Virginia, males outnumbering females, seven to one. Also present were 32 Africans, 15 men and 17 women, a more equal sex distribution that lent it to family formation. There were also four Indians, who like the Africans, were “in ye service of several planters” (Ferrar Papers 1509–1790 as cited in McCartney 2000 Vol. I: 52).

Most of the ‘20 odd’ Africans who arrived in Jamestown August 1619, remain virtually anonymous. There were three Negro men and two Negro women listed later as servants living in the Yeardley Household. Angelo, a Negro woman who disembarked from the Treasurer three or four days after the first group became a member of the Captain William Pierce household (Hotten 1874 as cited in McCartney 2000:174). Antoney Negro and Isabell Negro arrived in 1621 with a newborn son they immediately had baptized. Although these people and the other first African settlers are mostly lost to history, the act of baptizing their son allows us a small window into the cultural patterns and beliefs of these earliest African in America (Russell [1913] 1969:24 ftn.34).Read more about the first African American Family.

Who Were the First Africans?

Nearly three quarters of the Africans disembarking in the lower-Chesapeake (York and Upper James Basin) came from more southerly parts of Africa from the Bight of Biafra (Present day eastern Nigeria) and West Central Africa, then called Kongo and Angola. The inheritance practices of the Virginia gentry, especially those in York and Rappahannock districts, perpetuated the concentration of enslaved African people who had common cultural characteristics. The resulting ethnic concentration of enslaved communities originally from West Central Africa and the Bight of Biafra in these regions facilitated continuity of family and kinship networks, settlement patterns, and intergenerational transmission of African customs and languages.

Lower Chesapeake Africans mostly came from along the Calabar Coast and West Central African Kongo and Angola Regions.

Among the Africans who came, were “Antonio a Negro” in 1621 aboard the James and in 1622 the Margaret and John brought “Mary a Negro Woman (Hotten 1874 as cited in Russell [1913] 1969:24 ftn.34).” Once in Jamestown, Mary was taken to Bennett’s Welcome Plantation. There she met Antonio, one of only five survivors of a recent Tidewater Indian attack that had killed 350 colonists in a single morning. Their meeting was as fortuitous as Antonio’s survival of the Indian attack.

Although some scholars argue that the Antoney Negro, who lived in Elizabeth City in 1624, was the same person as “Antonio a Negro” who arrived in Virginia in 1621 aboard the James, a more solid argument can be advanced that they were different persons (Breen and Innes 1980:ftn9,116).

When Antonio appears in the 1625 muster of Bennett’s Welcome with the anglicized name Anthony Johnson, Mary appears too as the only woman living at Bennett’s plantation. Sometime after 1625, Mary and Anthony Johnson married. Somehow, they acquired their freedom. A section on Free Africans on Virginia’s Eastern Shore found in this module tells more about people like Mary and Anthony.

Breaking the Bonds of Slavery

Seventeenth century slavery in the Chesapeake was flexible enough to provide enterprising Africans the opportunity to earn their freedom. Through the head-right system, colonists who helped populate the colony with slaves or indentured servants received ownership of 50 acres of Virginia Company land for each laborer they purchased or indentured. Upon completion of their term of service, freed indentured servants received “freedom dues,” usually a quantity of clothing and corn. Slaves were sometime freed, or more often allowed to work for themselves, save their earnings, and seek to buy themselves out of slavery.

Most of the free Africans and their descendants in Virginia became free in the 17th and early 18th century before chattel slavery became the law of the land. Many of them lived on Virginia’s Eastern Shore.

Freed slaves as well as former indentured servants could lease land, work, buy slaves, or indenture other servants thus gain head-rights and ownership of private land. Africans could, and some did participate in the head-right system. Most of what little we know or can speculate about Africans’ cultural life in 17th century Virginia comes from the documentary evidence they left as they reached beyond the anonymity of enslavement to become recorded propertied men and women, taxpayers, plaintiffs or defendants in court proceedings.

The law required African women to pay tithes to the colony in shares of tobacco and other crops they might raise. African men married to African women, had to pay the tithe for their wives and, if they had daughters for them as well. This made marriage a costly proposition, but marry they did.

African families inter-married. Marriage broadened kinship ties and networks. In early Colonial Virginia, the boundaries between races and those free or in bounds as servants or slaves were permeable. Some of the African men married English women who were indentured servants or American Indian women enslaved or bound in servitude. Through these relationships, they created inter-group community networks. In order to prevent separation of the family through sale of a member, free people of color often bought their family members.

In addition to forming community through marriage, Free Africans of Northampton also established community ties through commercial transactions.

Africans in Virginia married among themselves, with new African immigrants, the English, and American Indians. By the end of the 17th century, there were about 300 Africans and their descendants living in Virginia and most were enslaved.