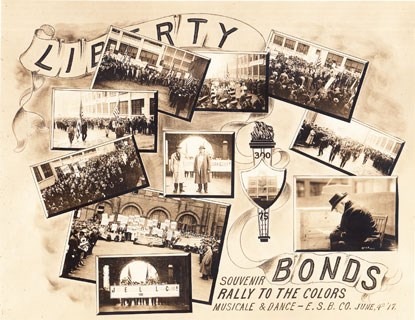

NPS PHOTO The First World War, then known simply as the Great War, was in Edison's time the deadliest war in human history. The war would be waged between the Allied Powers of the United States, France, the United Kingdom, and Russia against the Central Powers of Germany, the Austrian-Hungary, and the Ottoman Empire. However, the four years of conflict would be made even more horrific by the introduction of mechanized warfare, with new advanced technology as a result of the latest industrial age. New innovations in weaponry such as machine guns, tanks, and airplanes all had the potential to cause horrific losses of life on the battlefield. World War I was significant for Thomas Edison's life and business even before America's entry into the war in April 1917. Unlike contemporaries such as Henry Ford, who advocated a strict pacifist approach, Edison believed in preparedness, in response to potential threats against the United States. This philosophy advocated arming the United States military for war, with the assumption that America would eventually be forced to enter the conflict. Various prominent individuals during this period, including General Leonard Wood, former U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt , former secretary of war Henry Stimson, and various other prominent politicians and businessmen also advocated this approach, eventually gaining the support of President Woodrow Wilson. Thus, Edison aided the United States military, particularly the Navy, in preparing to defend American shores from enemy attacks, particularly from submarines. Edison greatly feared the consequences of warfare with modern industrial weapons. As he said in an interview with the New York Times in October 1915,"Science is going to make war a terrible thing –too terrible to contemplate. Pretty soon we can be mowing down men by the thousands or even millions almost by pressing a button." This motivated Edison to aid the United States military in arming itself for defense against potential enemies. During the spring of 1915, Edison described his preparedness ideas, basing them on the stockpiling of munitions and military vehicles and on recruiting a large army of reservists from the private sector, highlighting the concept that military preparedness needed to be organized along industrial lines.

NPS PHOTO Later that year, Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels recognized the usefulness of Edison's technical expertise, and offered Edison chairmanship of the new Naval Consulting Board. In a letter to Edison, Daniels wrote "One of the imperative needs of the navy, in my judgment, is machinery and facilities for utilizing the natural inventive genius of Americans to meet the conditions of warfare as shown abroad…" To meet this need, Daniels established an organization that would consist of a group of scientists and administrators responsible for evaluating the public's ideas for innovations to the U.S. Navy. Many of the ideas reviewed, however, were deemed to have very little value, and of the 11,000 ideas gone over by the Board, only 110 of them would even be seriously considered, with only one, the Ruggles Orientator (a precursor to the flight simulator) actually being produced and implemented by the U.S. Navy.

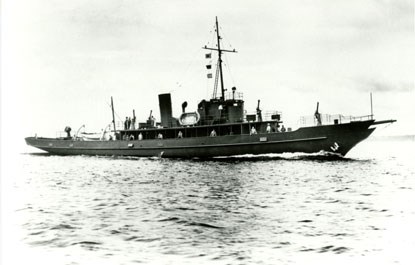

NPS PHOTO Edison, wanting to be spared of much of the bureaucratic work of the Naval Consulting Board, played a largely ceremonial role as chairman. Far more significant were his private endeavors to provide for the U.S. Navy, particularly in detecting enemy submarines at sea. By 1917, the year America entered the war, Edison had dedicated all of his time to naval research. Particularly notable are Edison's experiments conducted at Eagle Rock, NJ, where he outfitted a laboratory out of an old casino to investigate locating gun positions via sound. Even more notable was his work aboard the USS Sachem on the Long Island Sound. The USS Sachem was a private yacht outfitted by the U.S. Navy for Edison and his employees. From August to October in 1917, Edison conducted experiments aimed at the camouflaging of ships and torpedo detection. To this end, the Sachem was equipped with instruments to detect submarines by sight, sound, and magnetic field. In all, Edison would spend eighteen months in the field, and would conceive of a total of forty-eight different projects, including a hydrogen-detecting alarm to avert the danger of undersea explosions, vaseline and zinc antirust coating for submarine guns, and an antiroll platform for ships' to ensure accuracy in rough seas. However, despite his various experiments and innovations, Edison nevertheless grew increasingly agitated with the Navy for failing to implement any of his ideas. Of the forty-eight new inventions and improvements he proposed, the Navy failed to develop any of them beyond the prototype stage. This later caused Edison to accuse them of lacking the imagination or the foresight to see the usefulness of his work. As he wrote in 1918, "Nobody in Naval will do anything on the account of taking risks that an innovation will bring in … no training at Annapolis to cultivate the imagination."

NPS PHOTO If Edison's work during this period had one significant effect, it is the resulting creation of what became known as the Naval Research Laboratory. Edison firmly believed in the necessity of a federal research laboratory to produce new ideas and inventions to improve the military. This is significant because previously, the United States federal government had only introduced such institutions on a limited basis, such as the National Academy of Sciences during the Civil War. At the very first meeting of the Naval Consulting Board on October 7th, 1915, Edison's proposal of the creation of a permanent naval research laboratory was adopted. Specifically the proposal included a laboratory on the water where a ship could be docked, nearby a large city, and would be run by civilians rather than the military. In 1916, Congress appropriated $1 million ($21.1 million today) for the new laboratory, which was less than the suggested $5 million ($115 million today). This forced the Board to develop a more scaled-back, less equipped laboratory, run by naval officers instead of civilians, and with more emphasis on basic scientific research and testing, rather than production. Also, construction of the laboratory would not be able to begin until the early 1920s due to the war. Despite various problems, including Edison's later objections to the changes to his original proposal, the 1923 opening of the first Naval Research Laboratory hallmarked the beginning of a permanent commitment to research and development. This would begin a new era of government-funded research, which would lead to various inventions that are still in use today, such as radar, jet engines, GPS, nuclear weapons, and the Internet. |