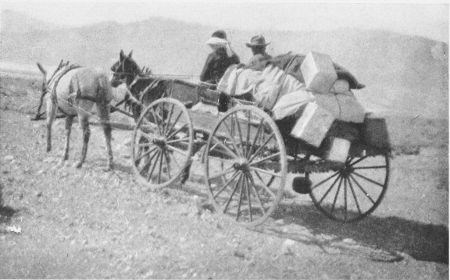

Courtesy of the California State Library. Edna Brush Perkins was an active suffragist from Cleveland, Ohio and an avid travel writer who fell in love with Death Valley. She visited Death Valley with her friend Charlotte Jordan and recorded their beautiful and difficult travels in the desert in White Heart of the Mojave. Her poetic musings on the dangers and beauty of Death Valley still resonate today. Born in 1880, Edna Brush grew up in an affluent family home as the daughter to American engineer Charles F. Brush. While her father invented the arc lamp and the first fully automatic wind turbine, Edna thrived on the arts and activism. She indulged in piano and painting to occupy her time while she was at home and spoke out for women’s suffrage in Cleveland through the passing of the 19th Amendment. Her father was raised with traditional Victorian beliefs and believed Edna’s place was in the home, not on the streets or in a political movement. Edna Brush married Roger Perkins in 1905, becoming a mother, artist, and activist in her own right. She organized and lectured for women’s suffrage in Cleveland from 1912 through 1920. Temporary action was not enough for Brush, however, so she chaired the Woman’s Suffrage Party of Greater Cleveland (1916-1918) and helped found the Women’s City Club of Cleveland in 1917. The Women’s City Club empowered women to get involved in civic affairs while also providing a community for women to discuss how to use their influence to promote the welfare of their city. While the passing of the 19th Amendment was not the end of the suffrage movement, nor was it the end of women’s political activism, Edna Brush decided it was best to take a vacation. She hopped on a train to California with her good friend Charlotte Jordan in search of a small respite from the stresses of daily life. "Charlotte and I knew the outdoors a little. Though we were middle-aged, mothers of families and deeply involved in the historic struggle for the vote, we sometimes looked at the sky. In our remote youth we had had a few brief experiences of the mountains and the woods; I had some not altogether contemptible peaks to my credit and she had canoed in the Canadian wilds, so when we decided that a vacation was due us we chose the outdoors." On the train, they decided to experience the curious expanse of desert known as Death Valley. In seeking maps and advice for their trek, the women were discouraged every step of the way. Hotel owners and friends provided no assistance in planning their drive into the desert and even when they sought help from Automobile Club of Southern California, they were told to visit San Diego instead. "It seemed to be unheard of for two women to attempt such a thing; the distances between the towns where we could get accommodations were too great and the roads were apt to have long stretches of sand where we would get stuck. Our friends drew a dismal picture of us sitting out in the sagebrush beside a disabled car and slowly starving to death." Finally, in Saratoga Springs near the southern tip of what is now Death Valley National Park, the women were greeted with enthusiasm and admiration for their desire to brave the difficult desert landscape. After planning, Perkins and Jordan took a train with the Sheriff Julius Meyer (their official “Worrier” for the trip) to Beatty, Nevada. There, they loaded an old wagon with more supplies than seemed reasonable at the time and hitched up their “desert-proof” steeds, Bill and Molly.

From Edna Perkin's book White Heart of the Mojave, courtesy of Project Gutenberg. Their adventure into Death Valley looked much less like a modern trip into the park today, bearing much more in common with the treacherous journey of the ‘49ers. Thankfully, their guide helped them conserve their water and kept them from coming to any serious harm, but they still were forced to endure the heat and inhospitable climate of Death Valley. |

Last updated: October 1, 2021