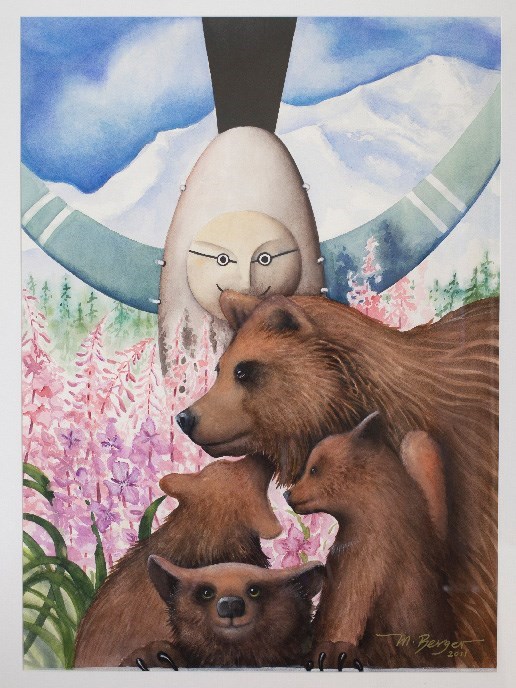

Marian Berger-MahoneyDenali Spirits This piece is a blessing, an invocation of the three elemental spirits I experienced during my residency: human, animal, and mineral. It is important to place the human experience within the realm of these places, which is why so much of my work focuses on the use of artifacts and the relation to place. The mask is Athabascan, Deg hit'an from the lower Yukon. It is a messenger mask representing a crow. Runners wore the mask on their way to other villages to invite them to a ceremony performed to increase the abundance of wildlife. There was one point during my residency when I had a close encounter with a grizzly bear near the cabin, and while I felt no fear at the moment, there was instead this deep, personal connection to its spirit that has resided with me ever since. — Marian Berger-Mahoney, 2011 Marian Berger-Mahoney is a painter from Volcano, Hawaii. Currently she is concluding a three year project for the San Diego Zoological society illustrating a book entitled Living Endemic Birds of Hawaii. She grew up camping, hiking, and horseback riding in Alaska and in the early seventies studied red foxes residing at the East Fork Cabin. She is planning to create two-dimensional pieces that are representational close-ups, such as the inner beauty of a wildflower. Visit her website.

Gina HollomanToklat Wolf In the wee hours, almost every morning, I had one of the most thrilling and haunting experiences of my residency. Directly behind the cabin, wolves howled as they returned from an evening hunt. Then I heard answers as howls of welcome came from a den situated a mile upriver from the cabin. I only saw one wolf during my residency, a large black male with watchful yellow eyes. He is the inspiration for the Toklat Wolf. The howling of the wolf pack, along with the memory of those curious penetrating yellow eyes are etched forever in my soul. — Gina Hollomon, 2011 Gina Hollomon is a studio clay artist from Anchorage, Alaska who has a background in biology. She has created several installations including life-size flocks of sandhill cranes, pintails, and Canada geese appearing to fly in one window, up a staircase, and out another window at the Nordale Elementary School in Fairbanks . She has gained inspiration from her volunteer work with the Bird Treatment and Learning Center in Anchorage , and is looking forward to absorbing and observing the natural rhythms of Denali. Visit Gina Holloman's website. Carolyn KremersTo my surprise, a favorite aspect of my 10-day sojourn in Denali National Park as an Artist-in-Residence turned out to be the blessed, contemplative evenings at the Upper East Fork cabin, after all the buses had disappeared. I didn’t expect to fall so in love with that place—the cabin, its history and ghosts, its psychic energy and weathered beauty, its porch, and (most of all) its surprises. I hope that some of that magic shines through in the essay I’ve written for the park, as well as in the several poems and prose pieces that I expect to complete in the future, as they emerge from my research and experiences, over the past thirty years, in what Alaskans call Denali. While at the cabin, I read and journaled a great deal, but not in any organized fashion. Unlike my town-and-forest life in Fairbanks, at the East Fork I abandoned (in many respects) order, forethought, and responsibility, and instead did exactly as I pleased. There was no phone, computer, Internet, work schedule, calendar, or pile of email to intrude upon me. Instead, like a songbird I could follow my heart and soul every day and every evening. This was an incredibly liberating feeling, and one that does not come often to me in the hectic, 21st-century vortex we sometimes (mistakenly) call life. Perhaps this liberated feeling is what channeled me into the prose poem, “Finding the Route”—a piece that became a visual/tonal model and gateway for the other six parts (or settings, as in musical settings) of “The Day I Hiked Up Stony Dome.” History, change, female experience, the natural world, the cosmos, and human relationships to nature and culture: these are elemental things that deeply interest me. Every place contains multiple layers, as does every person. Yet the history and spirits of a place are not always evident. If we listen and look, however, and reach out with our hands and hearts to touch and pay attention, we can begin to discern what is truly here: what has come before, what is now, and what may be to come. This ability, I believe, is one of the highest gifts and responsibilities of the human species. — Carolyn Kremers, 2011 The Day I Walked Up Stony DomeI glanced again at the detailed bus schedule with its uninviting heading: Denali National Park and Preserve Visitor Transportation System (VTS)—All VTS buses are green! Then folded the half-sheet of white paper covered with numbers and tucked it into the small Ziploc bag inside my pants pocket. If I walked up the mile-long, dirt “driveway” from the cabin to the Park Road by 8:15, I should be able to catch the bus that had departed at 6:15 that morning from the Wilderness Access Center (WAC), near the Park entrance, 43 miles to the east. The morning was cool and damp—Tuesday, July 26th—and I was headed to mile 62 or so and Stony Dome, elevation 4700 feet. Maybe it would rain today, maybe not. I didn’t care. I was going to the massive, emerald mountain that I had wanted, for 30 years, to stand on top of. Some things take a long time to materialize. The bus driver’s name was Beth. At the Toklat River rest stop (mile 53), when I asked her where she was from, she said Rhode Island. This was her seventh summer, driving a bus for the Park. For a time she had lived in the Denali community year-round. “I loved it!” Beth said. “But now I’ve returned to Rhode Island, which is really my home. It’s where our country began, you know. And—well, I just like the history there. Old, old houses from the 1600s. I live in one. Maybe it’s crazy to give up one thing I love—living here in Denali—for another. I don’t know. But I’m studying to be a social worker. (So that’s what she does in the off-season, I thought.) Then I can work in Rhode Island or Alaska—or anywhere. That’s my hope, anyway. And maybe my dream. We’ll see.” I liked Beth. She was young, slight, fit, and wisps of light-colored hair fell from beneath her white visor cap, along with a generous smile. She knew just how much to say to us 30 or 40 passengers, captive in the green-painted school bus. She pointed out glacial erratics and Dall sheep at Polychrome Pass; a golden eagle perched way up on a rock; a patch of blue alpine forget-me-nots near the road; the fast braids of the Toklat River, with Divide Mountain rising between. Beth wasn’t just a bus driver. She was a naturalist and an experienced, unofficial guide—and she was the person with whom many of these visitors would spend their entire day, 6:15 am to 5:45 pm, all the way to Wonder Lake (mile 85) and back. I had intended, after studying my topographical map the previous night, to get off the bus at the west end of Stony Dome, where the Park Road crosses Little Stony Creek. I thought I would follow the drainage southeast and curve up onto the southern flank of the mountain. Several people in the Park had told me that this was the easiest approach to the summit. Beth had a different idea, though. She suggested I begin hiking sooner, from higher up at the Stony Hill Overlook (where the tan buses—the more expensive, narrated-tour buses—pull up to make a photo stop and shoot the postcard view). “You can save a little elevation gain that way,” she said. After Highway Pass, our bus began chugging up the switchback turns toward the overlook and the famous view of Denali—“Mount McKinley,” highest peak in North America, 20,320 feet: the view that looks like two giant mounds of delicious, homemade vanilla ice cream, piled in a rich-green bowl with a tiny gravel road etched along the bottom. On one of these turns, we saw the bears. There were three: a big blonde sow and her two cubs—one cub blonde like the mother and one cub cinnamon and black. A few days before, I had seen another threesome—a big brown sow with larger cubs, both light brown—near the bridge at big Stony Creek, before the road begins the climb up Stony Dome. The mother had been digging along the embankment for roots and ground squirrels, the cubs frolicking and chasing each other among the willows and hollows above. Now this younger bear family was traveling from that same direction, fast, up the base of the mountain. The bus chugged higher and we lost sight of the bears. I thought of my first ride on this road, in 1981 with my partner Larry, from Boulder: how we rode all the way to Wonder Lake and camped there in the rain. (The buses were yellow, then, and free, with no seatbelts and no reservations. You just hopped on and rode.) Since moving from Colorado to Alaska in 1986 to teach in a Yup’ik village, I had made many visits to this Park— biking, backpacking, cross-country skiing, day-hiking. I could probably list all the names of friends and family I had brought here, over the years. But I couldn’t begin to count the numerous bus-rides they and I had made on this road and up this mountain. Beth slowed the bus and looked into the big, rear-view mirror at the many passengers seated behind her. The highest point on the road was coming up, I knew, along with the overlook and (had it been a clear day) the ice-cream postcard view. “Does our hiker still want to get off the bus here?” she asked. “Yes!” I called from the back—and the bus, with all its people, seemed suddenly silent. Beth parked the bus at the side of the road and I stood up in my raspberry-colored fleece pullover and thin, black gloves. Shrugging into my daypack as gracefully as possible, I tried not to knock my collapsible trekking poles, strapped on one side, into the people sitting nearby. With big Nikon camera and smaller binoculars in hand, I began making my way to the front of the bus. I could feel people scrutinizing me—my stuffed pack, muddy Gore-Tex hiking boots, and silver ponytail. Can they guess that my sixtieth birthday is just a few months away?“Okay, you saw the bears,” Beth said, her voice practiced, steady, kind. “So you know where they’re headed. Up here, same place as you. They’re still some distance away, though, so you have some time. Just pay attention and be aware. Have a good hike!” Humans seek danger sometimes. We choose it. Is it because we are drawn, like magnets, to the thrill? The challenge? The unknown? I think maybe so. And I think we have some primal need to escape our house-bound, vehicle-bound, city-and-town-bound, screen-bound, electronics-bound, mobile-device-bound—that’s it: device-bound—existence and return to something deeper and more simple. Maybe something more true. Danger can take us there. It’s not easy to walk alone up a mountain without a trail. Neither is it easy to walk alone among bears. Maybe it’s not easy, because I’m a female and a person without a gun (just pepper spray). But I think it’s more complex than that. We have all descended from hunter-gatherers. There is something ancient and heady, I think—re-energizing, addictive—about walking up a hillside and out of view of any human being: back into God’s country and freedom (some people call this wilderness), where anything can happen and usually does. To walk on up that hill, ears open, eyes open, occasionally looking back in the wind at the open tundra—a hundred ridges in the distance and the orange lichen and gray rocks close by—checking to see if three furry animals (or two or one—it only takes one) have popped up unexpectedly: that’s a singular kind of freedom. Most grizzlies in Denali dislike the scent of humans. They’re wild animals, and unless they’re surprised or threatened, once they recognize a creature as human, they will run away or else ignore the person. Our job is to be sure we don’t surprise a bear or make it feel threatened—particularly a sow with cubs... Just pay attention and be aware. And if by chance a grizzly charges, don’t turn and flee. Grizzlies can run faster than 30 miles an hour. Stand your ground. Face the bear, make noise, call its bluff. Wave your arms, perhaps, to look big. And wait to shoot the pepper spray until the bear is within 30 yards... You walk east, following the contours of the land, glassing the mountainside now and then, in search of the best route up. After awhile, a road-grader (or is it a bulldozer?) can be seen down below—and heard, when the wind is just right—scraping and nattering away. You lose sight of the road, reach a ridge, look down into a lovely, narrow pass, and realize that you must cross over this pass, then climb on up the mountain. You’re thinking it’s time to take a break, perhaps, and eat half a sandwich, when— THERE!— on the left, ambling up the hill from down below, right onto the pass, seeking food (always food) and freedom: here come the bears. Big blonde mama and her two spring cubs: the blonde and the cinnamon/black. Will they see you? Will they catch your scent and turn...toward you, or away? Or will the little rowdy one—the cinnamon/black, the mischief-maker—gambol so far off track that he finds himself on your side of the pass? (Surely this is a he—so curious and quick, zig-zagging off track in every direction, so unlike the big mother and the little blonde.) With binoculars and heart-pounding, quickening delight, you watch as the three powerful, healthy, hungry bears move on, travel on, across the giving tundra and the day. Oblivious to you, they amble over the pass and down—into the valley to the west and a creek, in the direction of Denali, on into the ice-cream postcard view, the picture that no camera can capture or ruin or hold. So I climbed, at last, into a broad green saddle above the slippery gray scree and spied a big, old brown scat pile and new green scat pile, grizzlies’ for sure. Sturdy stems of dryas—topped simply now with dark blond twirls—made a pointy backdrop for the translucent lemon dots of my winsome favorite: Alaska poppies. Also called Icelandic, I used to think (but Icelandics are bigger). I gave a shiver for this cold, beloved North and turned around to face the valley and catch the suddenly sunny July view, take a break, shake off my daypack. In the distance, the Park Road re-appeared, snaking back toward Polychrome, the road-grader just a dot now, silent in its smallness and the breeze. Time for gorp before the summit, I told myself, and time to drink some water. The darker clouds were drifting in, but I felt just at home. Then suddenly—some raisins, a cashew, and two colored M&M’s poised, delicious, in my mouth—the first crunch down and I no longer stood just shy of emerald Stony Dome’s massive top. You and I were standing in our heavy leather boots, crunching down on what you always brought for us—raisins and fractured chocolate bar: Hershey’s or Cadbury—and I was young and innocent, and you were...not old but wise. Daughter, father, we stood in Colorado, high up in some alpine bowl or on a rocky ridge. And all those lemon dots had morphed to blue-white columbine. Then came tears and great, deep sobs, and the green and gray and blue and white and yellow merged into one vast blur. I sat down on a rock and let the hot tears fall and felt that blur: that I will never ever see you again on this Earth except like this. In memory. Dreams. Old photographs. Words. And if I lose those shimmers? It was then I understood, again, the legacy you shared so freely—from when I was just an infant, six months old. A love of the mountains. A need for high places. A confidence and certainty that the route may always be found.

Just above me, at what I hoped was the crest of the mountain, I glimpsed a thick ball of light-brown fur. I stopped to glass the scene. The ball was moving slightly. Then the fur stood up, two feet tall, and I saw: a hoary marmot. It’s fine, tan coat with black-tipped hairs sparkled in the sun. The pink nose twitched—dark eyes, black mask, white forehead—while the rodent’s little hands hung motionless, black and human-like, at its side. Extra quietly, I continued climbing, angling left, trying not to disturb this little king of the mountain. The marmot—still standing motionlessly—sniffed the air, its eyes on me, then kept on chewing stems. I reached the summit, and the marmot dropped back down into green stubby grass and yellow blooms of alpine arnica. Without moving an inch from where I had first spotted it, the animal buried its furry head in a crevice of gray rocks, digging again, I guessed, for roots: so mouth-watering, so scrumptious, that it had no time or use or fear—not even a whistle—for me. So. The top of Stony Dome was flat, almost like a soccer field! Who would have guessed, from down below? I could see 360 degrees, effortlessly, in all directions. How had this panorama looked 11,000 years ago, when men, women, and children—all hunter-gatherers—began migrating from Asia across the broad Bering Land Bridge, some finding their way here, into what is now called the Alaska Range? Near the end of the last ice age, before the dry and chilly, grass-and-sage-covered arctic steppelands became warmer and wetter and gradually changed to tundra and trees (spruce and birch), many large carnivores roamed the steppes of this vast region. There were woolly mammoths, I’ve read, and steppe bison, steppe lions, and probably cheetahs. Miniature horses with reddish coats and black legs, manes, and tails grazed the steppes, along with wild asses with chestnut-colored coats and blonde manes and tails. Saber-toothed cats caught rodents and other small mammals, and shaggy, black musk oxen munched on plants. Short-faced bears, twice the size of Alaska grizzlies today, likely stalked many of these four-leggeds for prey. Had Paleolithic hunter-gatherers of the late Pleistocene climbed partway up this mountain with their stone-tipped spears to scout for animals, too? Or was there no Stony Dome and instead just rolling steppe? A thousand years ago and into the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, those ancient, Paleolithic wanderers’ descendants—the Athabaskans—likely migrated in and out of this area in their search for caribou, moose, sheep, and bear. In the huge region where Denali National Park exists today, five nomadic Athabaskan groups—the Koyukon, Tanana, Ahtna, Tanaina, and Upper Kuskokwim—gathered roots, mushrooms, berries, and medicinal plants, and they hunted and occasionally fished. Bands of two to five families from a single group usually traveled together, moving between seasonal camps and a more permanent winter dwelling, which they built several feet into the ground. Such a band might traverse an area of 2,500 square miles in their search for meat and sustenance. Who could say which other humans might have walked here? Musing on this as I turned slowly in a circle, taking in the views, I began to shiver in the wind. Pulling my wool hat and blue Gore-Tex rain jacket from my pack, I put them on and sat down on a rock beyond the marmot. Time to eat my own delicious lunch: bagel with cream cheese, half an apple, and one of my friend Sarah’s unbelievable chocolate-walnut cookies. Then I lay on my back with binoculars. A golden eagle circled up and up on some updrafts—each powerful wing tipped with five dark feathers, like fingers, fine silhouettes against the cloud-grey sky. I listened for the eagle’s call. No call, just an ever-higher circling and spiraling, until my head grew dizzy and I stood up and trained the binocs, instead, on valleys and mountainsides. Seven white Dall sheep, high up on scree. A small herd of caribou—nine, ten, eleven, twelve—grazing beside a river. Brown moose, big rack, browsing in a pond. (I’m not making this up, not one bit of it.) The greens and greys and reds and black of another hundred ridges. Rain was moving in, back at Polychrome. Now I spotted, far below to the south, near a streamlet in a valley, a tiny yellow dome tent with light-green fly and bright-orange poncho-person, two tiny backpacks with rolled-up sleeping bags (or maybe bear canisters?) tied on. I looked to the west toward Denali: shiny braids of the Thorofare River and some foothills, everything above that completely hidden by clouds. Surely the view of Denali from this high place, on a clear day, must be stunning. No matter, though. Up here on Stony Dome at last, I felt again what I have often felt in this huge park: a sense of all things big and small, now and before, united somehow and co-existing. Still trapped, on paper, in your official Denaalee* / Denali—

I could have gone down the easy way—west, then down the southern flank of the mountain and back to the Park Road via Little Stony Creek—but why take the easy way? I decided not to. (So much out here is like life—because, of course, it is life.) I would follow the contours of the topo map and the contours of the land, and test my skills. Heading southeast instead of west, I would aim to drop down into big Stony Creek—without dead-ending on a cliff. My route-finding skills—with eye, map, and compass—are not the best. (I don’t own a GPS or a cell phone and have no desire to.) Often, over the years, someone else has taken the lead with navigation: first my father, then the counselors at Girl Scout camp, later my friends and soul-mate companions. Traveling alone now, though, and sans 21st-century technology, there is only one way to get better at route-finding, and that is to practice. This is part of the magic of Denali. Not just the bears and the possibility of an eagle call or a wolf’s, not just the beauty and vastness and history, but the lack of established trails. A person is encouraged—indeed, forced—to find her own way. And, marvelously, once you look, you begin to see. After two hours of dropping down and ending up, after all, at a cliff, it took just ten minutes of side-hilling to the south and then I was facing—not a cliff—but (as on the route up) scree. Do-able scree. I planted my weight and each foot carefully, angling across the slippery rock-slope, not down, making sure to focus on progress and my boots—not on what might happen if I slipped—and soon enough I was standing safely just twenty feet above the drainage bed for big Stony Creek. A few Tarzan swings along big, dusty roots sticking out from the eroded embankment—hand-to-root, foot-to-slope—and finally my boots touched flat ground. Ah, map and feigned self-confidence: my thanks! A person can’t tell, from up above, what lies below. Often, though, what lies below turns out to be an unexpected gift. Here—amidst thick, scratchy, waist-high willows—lay a beaten trail. Part bear trail, I thought, part moose (and wolf?), part human, too, I bet. Surely this trail will take me to the water’s edge. And it did. At the creek, the country opened out: into early evening, water-music, and tundra views way back and up to where I’d been.I turned north and followed the singing creek toward the Park Road. Occasionally a tan tour bus rattled east, in the distance, kicking up dust. When at last I shrugged off my pack and sat among the boulders to drink from my water bottle, then stand and flag down the next green bus, I could feel it: this pricelessness. Of having spent one day doing one thing that I had wanted to do for years.

A light-colored grizzly bear gorged on red-orange soapberries at the swift edge of the silty East Fork. Up above the embankment, just before the East Fork bridge, our WAC-bound bus had stopped to watch. The summer sun still hung high, and the return drive to the Wilderness Access Center would take at least two more hours. Most of us, I suspected, were tired and hungry. But this was a perfect, up-close view of a furry, powerful bear. Dusty window latches were pinched open, dusty windows slid down, and hands with cameras, cell phones, and binoculars poked out into the evening air. I shot some photos, then trained my binoculars on the bear’s ever-moving form—rippling blonde shoulders, big furred hump, round ears, dark legs (nearly black), long shiny claws, black snout. The bear nuzzled and guzzled the tasty orbs. Then windows snapped shut and the bus powered on. Just past the bridge, I stood up with my daypack strapped-with-poles (which hadn’t been needed, after all) and signaled the driver to stop. He opened the front door. “Have a good night,” he said, deducing I must be staying in the cabin a mile down the driveway. “Thanks,” I replied, heading down the bus steps. “You, too!” I’m so lucky, I thought, to be staying in the East Fork Cabin. Built in 1928 by the Alaska Road Commission (ARC)—which constructed the 90-mile Park Road between 1922 and 1938—the Upper East Fork Cabin was ARC’s fourth of five roadside cabins. The cabin served as a cookhouse for the tent-camp crew that built the original, log trestle bridge over the East Fork River and then much of the road over Polychrome Pass. The log cabin provided protection for stored food (unlike the crew’s canvas tents, which were easily raided by wildlife). This rustic, 14-by-16-foot building was also where Adolph Murie—famed field biologist and wilderness advocate—lived for eight summers between 1940 and 1970, doing research on birds and mammals. Today the cabin is still used by scientists for research, as well as by winter backcountry ranger and dog-team patrols, and by artists-in-residence like me. Walking home down the driveway, I passed with pleasure the pink fireweed, yellow cinquefoil, tall blue larkspur, and gliding honeybees, all alight in the evening sun. Beyond the translucent, golden bodies of the bees and across the several, broad braids of the East Fork below, I could see the bear. It, too, was ambling—up the very same steep bank that I had slowly pulled myself up with my hands, willow-root by thick willow-root, foothold by rock-foothold, the day before, after walking the riverbed in the rain with a visitor from Park Headquarters. Now here came the bear, up that 40-foot slope as if walking a flat sidewalk, then onto the roadway right past a stopped green bus and unabashedly, naturally, on over the concrete and steel bridge. People on the bus honed in on the bear with binoculars—and so did I. Then I was walking briskly—on down the driveway and around a bend—out of sight.If the bear continued along the Park Road past the bridge, soon it would reach this driveway, up above. Which way would it choose?

Quickly I released the tight, metal latch that held each pair of shutters closed, then lifted out the huge nails (placed in strategic holes—by a park ranger or a tenant?—at the base of each shutter for further deterrence). With groans and creaks, the weathered-wood shutters swung open. Where is that bear by now? I wondered. With the key I’d been given, back at Park Headquarters eight days before, I unlocked the big steel padlock on the front door, then set my gear on the floor inside. After hesitating a moment, I hurried up the short hill to the outhouse, hurried back, and hooked the cabin’s screen door behind me (Where is that bear?). Maybe I wouldn’t sit out on the porch tonight (as always), savoring my dinner of fresh green salad with honey Dijon dressing and chopped hard-boiled egg (the precious vegies brought from Fairbanks), then leftover spaghetti with tomato sauce, zucchini, and parmesan cheese. Maybe I wouldn’t relax on the bench—in the blessed, bus-free silence—with just the birds for companions (and Squeaky, the ground squirrel, who lives under the porch). As always, there would be no other living human in this valley—none that I could see, anyway. I would stand outdoors behind the cabin at 8:00 pm (as always) with the Park’s black satellite phone in my hand, pull up the four-inch, black-plastic antenna tube, aim it at the sky, and press the POWER button. An image of a satellite floating in space would appear on the phone’s screen, then Looking for registration, and then—within seconds, usually—Registered. A series of short beeps, and the voice of one of the female operators at the Park’s communication center—or “ComCenter”—would answer. Hello, I would say, this is Carolyn Kremers. Just checking in. Everything is fine. Good. So you’re closing out your itinerary for the day? [The voice would invariably say this, no matter who the operator was.] Yes. And we can expect you to check in again tomorrow night? Oh, yes. Alright, thank you. Have a good evening! Lowering the antenna and turning off the POWER button, I would walk back indoors and replace the black phone in its bright-yellow, waterproof dry-bag. Usually in the evenings, there were just me and the spirits and the East Fork. And the fresh, fresh air—all colored—that settled every night in this place and on me: blue, then orange, then red or pink, then sometime after midnight never-black-just-dim. And the wooden bench that looked almost just like the one in the book, Snapshots from the Past, which lay on the sturdy dining table. In this book I had found several black-and-white photographs of Adolph Murie and this cabin. In one photo, he and his wife Louise were sitting on the bench on this porch, summer of 1965. This was the cabin from which Murie studied intently the habits and predator-prey relationships of a family of wolves that was denning just a quarter-mile away. His experiences, living in this cabin and observing animals and habitats in their natural states, helped convince Murie that Denali National Park should not become a place of automobiles, tourist facilities, posted signs, and developed trails. Oh Adolph, I would think later. With friends I’ve hiked, skied, and backpacked hundreds of miles in Alaska without trails. But when traveling for more than a few hours alone, I’ve usually opted for following a riverbed, creek drainage, ocean beach, or some other sort of trail. The trip to Stony Dome wasn’t so much about reaching the top, as it was about proving to myself that I could do something different: navigate a part of Alaska without trails, for a whole day, without anyone to help me. Now I will never look at that part of the map of Denali, or at myself, the same way again... All I could do that evening, of course (Where is that bear?), was make the salad and warm the spaghetti and sauce in a steel pot on the propane cook-stove. Then unhook the screen door and take my plate, with binoculars and pepper spray, out onto the porch (as always) and sit on the bench. And think about the day. This cabin. My father and mother. Pricelessness. Bears. And, in truth, all my blessings. Carolyn Kremers writes literary nonfiction and poetry, and is a dedicated teacher and lifelong musician. Her books include Place of the Pretend People: Gifts from a Yup'ik Eskimo Village (memoir), The Alaska Reader: Voices from the North (anthology), and Upriver (poetry). Upriver was a finalist for the 2014 Willa Award in Poetry, from Women Writing the West. Kremers' essays and poems have appeared in numerous journals, magazines, and anthologies, and she has taught at Eastern Washington University in Spokane and the University of Alaska Fairbanks. For ten months in 2008-09 and again in 2015-16, she was a Fulbright Scholar at Buryat State University in Ulan Ude, Russia. Visit Carolyn Kremer's website. Stephen LiasDenali Denali bombards the senses. It makes us acutely aware of our own smallness, while at the same time challenging and nurturing our own capacity to go higher, further, and deeper. It is a land of extremes and poignant contrasts. As I set out to represent some of these qualities in music, I chose to write themes that captured some of the most fundamental emotions and memories: immense landscapes, dangerous predators, snowcapped peaks, fragile animals, and (predictably) the great mountain overlooking it all. — Stephen Lias, 2011 Stephen Lias is Professor of Composition at Stephen F. Austin State University in Nacogdoches, TX. He is the founder and leader of Alaska Geographic's annual “Composing in the Wilderness” field seminar. He has had residencies at Rocky Mountain, Glacier, Denali, Glacier Bay, and Gates of the Arctic National Parks, and has written more than a dozen park-related pieces that have been premiered at conferences and festivals in Colorado, Texas, Sydney, and Taiwan. His compositions are regularly performed throughout the United States and abroad by soloists and ensembles including The Louisiana Sinfonietta, XPlorium Ensemble, the Fairbanks Summer Arts Festival Orchestra, and the Chamber Orchestra Kremlin. Visit Stephen Lias' website.

Mark WedekindEast Fork Roots As an Artist-in-Residence in Denali National Park, the whole park is your playground enticing you to come out and play. The historic East Fork cabin was a wonderful home base from which to explore and I used the long days of June to spend time in parts of the Park I had never been before. The large landscapes, raw geology and magical light are so inspiring, but the smaller things are often what pull my eye. Because of the cabin's location on the East Fork of the Toklat River, I spent plenty of time wandering the glacial braided channels. I was especially drawn to the willow and alder trees that had been washed out by their roots, tumbled in the flow of the river, then left in the sun, wind and rain on the gravel after the abrasive water had done it's sculptural work. This provided the inspiration for “East Fork Roots.” — Mark Wedekind, 2011 Mark Wedekind is a woodworker and furniture maker from Anchorage, AK . He has received several commissions, including 14 original benches installed at the John Butrovich Building on the University of Alaska Fairbanks campus. While he uses traditional techniques to create his art, and the physical work is completed inside his shop, his inspiration comes from spending time in the earth's wild places. Visit his website. |

Last updated: March 7, 2019