When I was hired as a Denali Mountaineering Ranger last fall, this season is not exactly what I was expecting. As far as I can tell, this is a pretty commonly held sentiment across the entire United States and world. Spring of 2020: not exactly what we were expecting.

Still, our team has been balancing ways to maintain rescue readiness and ensure our training is up to high standards, while also abiding by new social distancing rules, as well as state and federal mandates. It has been a challenge, but we feel fortunate that we are in a position to continue serving Denali National Park and the greater community.

Being new here, my expectations for what our rigorous pre-season training schedule might look like were open-minded. But even as a rookie, I can appreciate the intense adaptability our team has demonstrated to maintain high standards of performance. Training has been a tricky balance of telework and social distancing while maintaining the skills needed to be a functional Search and Rescue (SAR) resource: high-angle rescue, medical and CPR training, avalanche rescue skills, and helicopter crewmember skills and protocols. Some of these have been easier than others, but all have involved a lot of video conferencing and individual work, and many have lacked the teamwork elements that we love about working this job.

So when a SAR call came in on a quiet Thursday afternoon at the station, I was beyond excited to be using our skills and training. Don’t get me wrong--people getting hurt doesn’t bring me joy; however, the ability to work as part of a team to serve someone in need, and an opportunity to put all of my training to work, is something that I love.

Chris, one of my managers, called me into the SAR room. “Can you go grab Mik? We just received a call from ARCC (Alaska Rescue Coordination Center) that they want to hand off a rescue in the area to us.” Mik and I were just hired last year, and to allow for social-distancing across our team, she, Chris, and I were the only ones working from the station on this particular day.

We all gathered in the SAR room to listen to the details of the call. There are a list of important questions you need to answer before you send the cavalry in. When and where did this incident occur? What is the nature of the emergency? How can we contact the people involved? What patient information do we have? What is the patient’s age, sex, injury, and how did they get injured? What resources or equipment do they have with them? What resources do we have available and what kind of conditions are we dealing with? These are all things you need to consider when planning a rescue, and while maintaining the cardinal rule of rescue: don’t create more patients. If we, as rescuers, become injured or have an emergency of our own, not only can we not help the patient, we’ve also created a situation that will require even more resources.

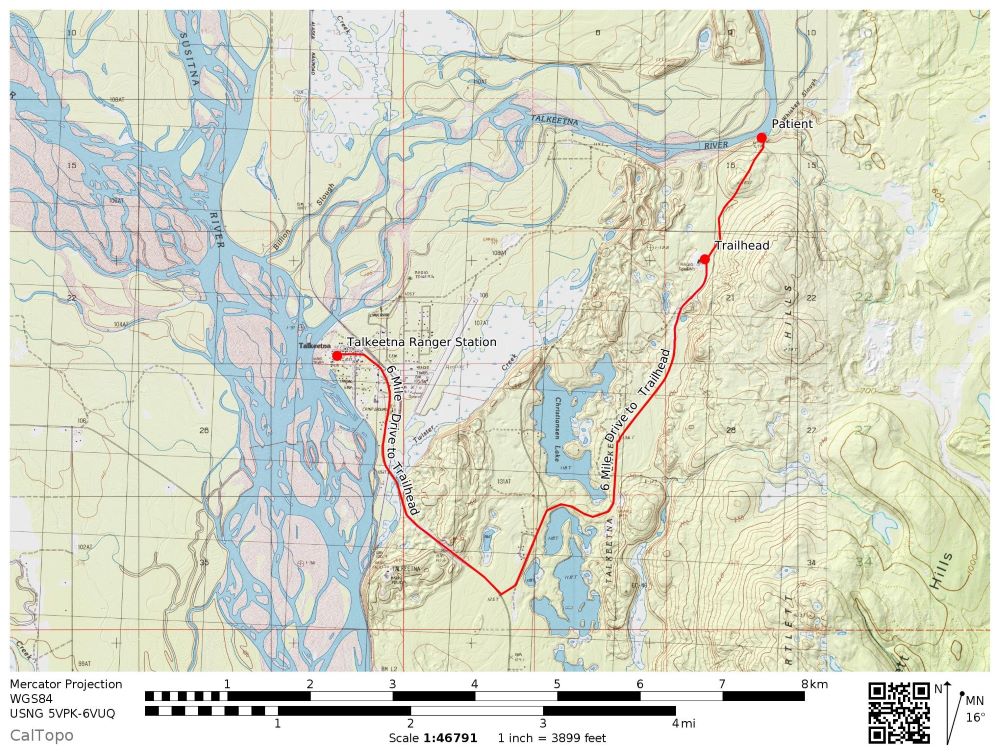

As rescues go, this one turned out to be really straightforward. At 3:08 pm, the ARCC received a call that a 56-year-old male snowmachiner had sustained a lower leg injury after rolling their snowmachine off of a steep embankment next to the Larson Trail. I plugged the coordinates into GPS and saw that the site was really easy to access: a ten minute drive, followed by an easy 1 mile ski over relatively flat ground. It seemed as though we should be able to start the rescue easily with the resources on hand. Together, we brainstormed what other tools we would need, and Chris started assigning gear for us to bring to the trailhead: “Chrissie, you go ahead and grab the patient litter, COVID PPE for everyone, and rope; Mik, take your medical kit and the patient packaging kit; I’ll grab our medical jump kit which has oxygen and some more advanced medical supplies. Everyone should have backcountry ski gear, helmets, and harnesses. Let’s all take our own vehicles to the trailhead so we can maintain social distancing.”

If you’re noticing that it seems suspicious that we received a call that was: close to town, didn’t require expensive resources (like the helicopter), was easily accomplished within normal business hours (no overtime), while only the boss and two rookies were on duty...you might be onto something.

Topographic Map of the Most Convenient Rescue of All Time

Reaching the trailhead, we assembled the patient litter and put our rescue gear inside. I offered to drag it to the accident site. At about 50 degrees fahrenheit, with not a single cloud in the sky, you couldn’t ask for more perfect weather in which to perform a rescue. Finding myself pretty sweaty by the time we were approaching the site, I asked Chris, “Do you think we want to call some backup so we don’t have to drag the patient up to the parking lot by ourselves?”

“Oh, yeah,” he replied, “Don’t worry, local EMS is on their way.” Being new to Talkeetna and thus far having an untarnished trust in my boss, I didn’t question what “local EMS” (Emergency Medical Services) were available or how Chris had managed to contact them without making any phone or radio calls in our presence.

Hauling in the Rescue Gear (NPS Photo / Mik Dalpes)

As we neared the accident site, Chris got out front and started peering over the edge, looking for the patient and yelling. “I think I just saw them waving down there. You two stage over by that tree, and I’ll downclimb to the patient and see what the situation is.” At this point, the trail was running along a flat bench about 100 feet above the river. The bank down to the river looked to have a slope angle averaging about 40°, or about the pitch of a black diamond ski run.

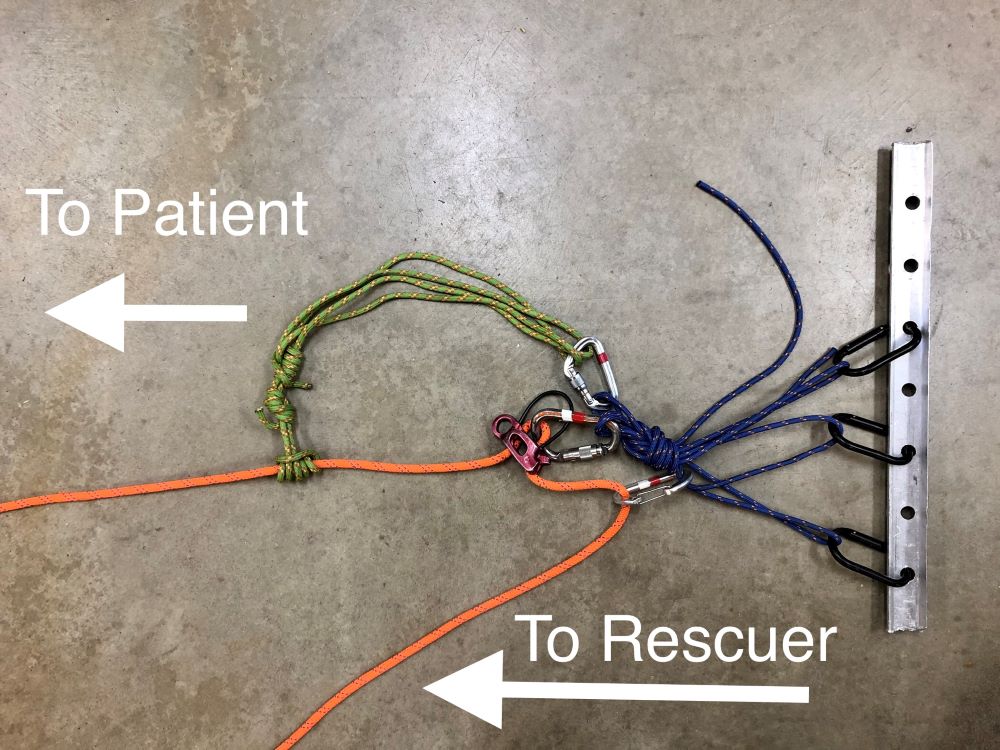

Mik created an anchor off a sizable birch tree (about 2’ in diameter) and set up a lowering system. Using the proper system, it is possible for one person to safely lower and control hundreds and hundreds of pounds with very little effort. You can also add a hands-free backup to this system, so that if anything happens to the rescuer tending the lowering system, the rope will automatically stop moving and be held in place.

Re-directed ATC (belay device) with a hands-free backup (NPS Photo / Chrissie Oken)

Chris scrambled back up the slope. “Ok,” he said, “the patient’s actually in pretty good shape. It seems like it might just be an ankle sprain but they can’t get back up the hill. I want you two to lower me down with the litter, convert to a raising system, and pull us back up.” Mik would manage the lowering system while I kept a visual on Chris as he went over the edge, and then Mik and I both would both create and manage the haul system. I still hadn’t gotten a visual on the person we were actually rescuing, but caught up in the concentration and enjoyment involved with setting up our rope systems, I accepted without question when Chris said that the patient was “tucked away just out of sight in a hole down there” and “doing fine.”

Chris and Chrissie prepare the litter for lowering (NPS Photo / Mik Dalpes)

So, let’s do a little math, with a lot of generous rounding: we’ll say that Chris, with all his gear on, is 200 pounds. Chris had estimated the patient was about the same. We’ll call the litter and rescue gear 50 pounds, and throw another 50 pounds in there for friction as we drag everything across the snow. We’ve all had a lot more time to work out these days, and while I don’t want to speak for Mik, I’m not quite capable of pulling 500 pounds 100 feet up a hill in an effective manner.

Lowering Chris over the edge (NPS Photo / Mik Dalpes)

Lowering Chris over the edge (NPS Photo / Mik Dalpes)

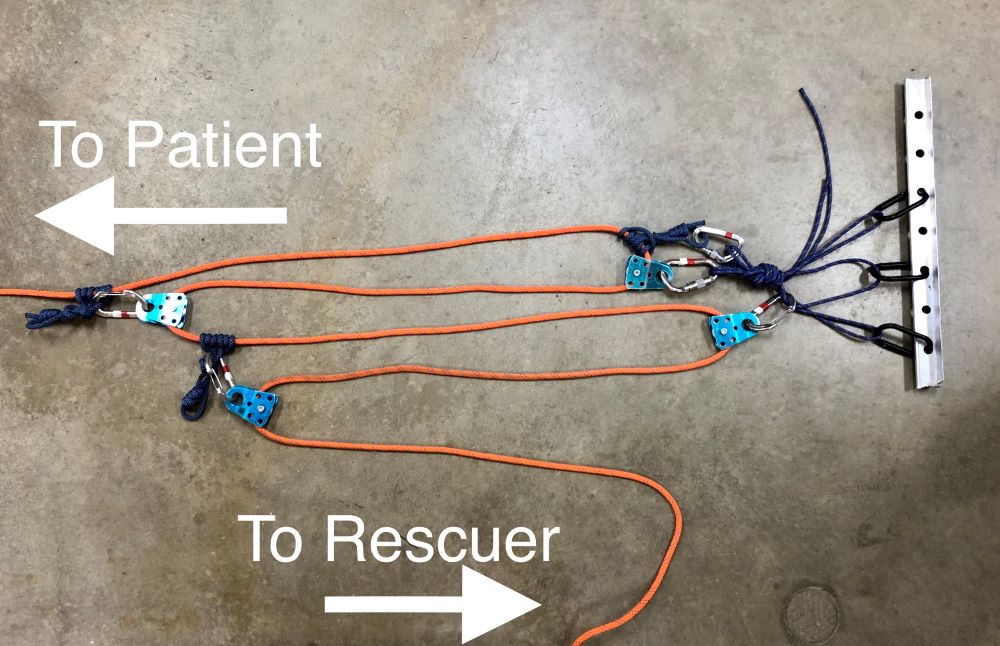

One of the things our team has practiced a great deal in the past few weeks is how to create mechanical advantage so that we are able to move very large loads without a huge amount of effort. This is a crucial skill to have a mastery of in a high angle-rescue situation. Using pulleys and friction hitches (which hold onto the rope in a place the rescuer determines), we are able to create a variety of different systems to make our job easier. Say, for instance, we set up a 9:1 compound pulley system. The term “compound” means that we have one pulley system acting upon another one to increase our advantage, and “9:1” refers to the fact that, for every 1 pound we pull on the end of the rope, 9 pounds of lift will happen on the patient’s end of the rope. The first record of humans using some form of these ingenious systems is generally agreed to be about 3 millennia ago! It is pretty amazing to consider how simple yet powerful they are.

9:1 Compound Pulley System (NPS Photo / Chrissie Oken)

9:1 Compound Pulley System (NPS Photo / Chrissie Oken)

After he reached the patient and got them safely into the litter, Chris called Mik and I over the radio to let us know that the patient was packaged and they were both ready to be raised back up. While mechanical advantage allows you to expend less force to raise a patient, it also requires more rope. Mik and I decided to start with a 9:1 pulley system to make our job easier, but that meant that for every 1 foot Chris and the patient were raised up the 40° slope, we’d have to pull 9 feet of rope through our pulley system. Because of this, we’d need to reset the system pretty frequently. The more mechanical advantage you’ve created, the more you need to reset the system.

“This feels pretty easy,” I said to Mik. “What do you think about going down to a 3:1?” She agreed. This would allow us to raise Chris and the patient faster and was an easy change to make. I wasn’t doing any math in my head at the time, but hauling on a 3:1 pulley system with a 500 pound load still meant we’d be pulling approximately 167 pounds up the hill. Given how doable this new system felt, this might have been another clue that something wasn’t adding up.

After a few minutes, we could start to see Chris’s helmet over the edge, and pretty soon he popped fully into view….with an empty litter and no patient.

“You’ve got to be kidding me.” Mik and I both gaped with quickly dawning comprehension.

“That was only going to work one time in your whole career!” Chris said, grinning. “You two might never trust me again, but you did a great job!”

“Great, you can carry the gear back to the trailhead,” Mik and I laughed, and then began to pack up our rescue equipment.

Debriefing as we skied back to the cars, we felt happy and satisfied after a really fun rescue drill. Even though this season has felt weird and disjointed in a lot of ways, it felt like a real success to roll up to a “real-life” scene, perform as a team and prove our “rescue readiness” (in a safe way in this new COVID world), and have a happy outcome (Chris is lucky we didn’t push him back down the hill after dragging him up it).

|

May 15, 2020

|

Last updated: May 15, 2020