2021 marked the 20th anniversary of the Clean Mountain Can (CMC). In 2001, spear-headed by mountaineering ranger Roger Robinson and made possible by a conservation grant from the American Alpine Club, the first 50 CMCs were tested on the mountain by expeditions on a voluntary basis.

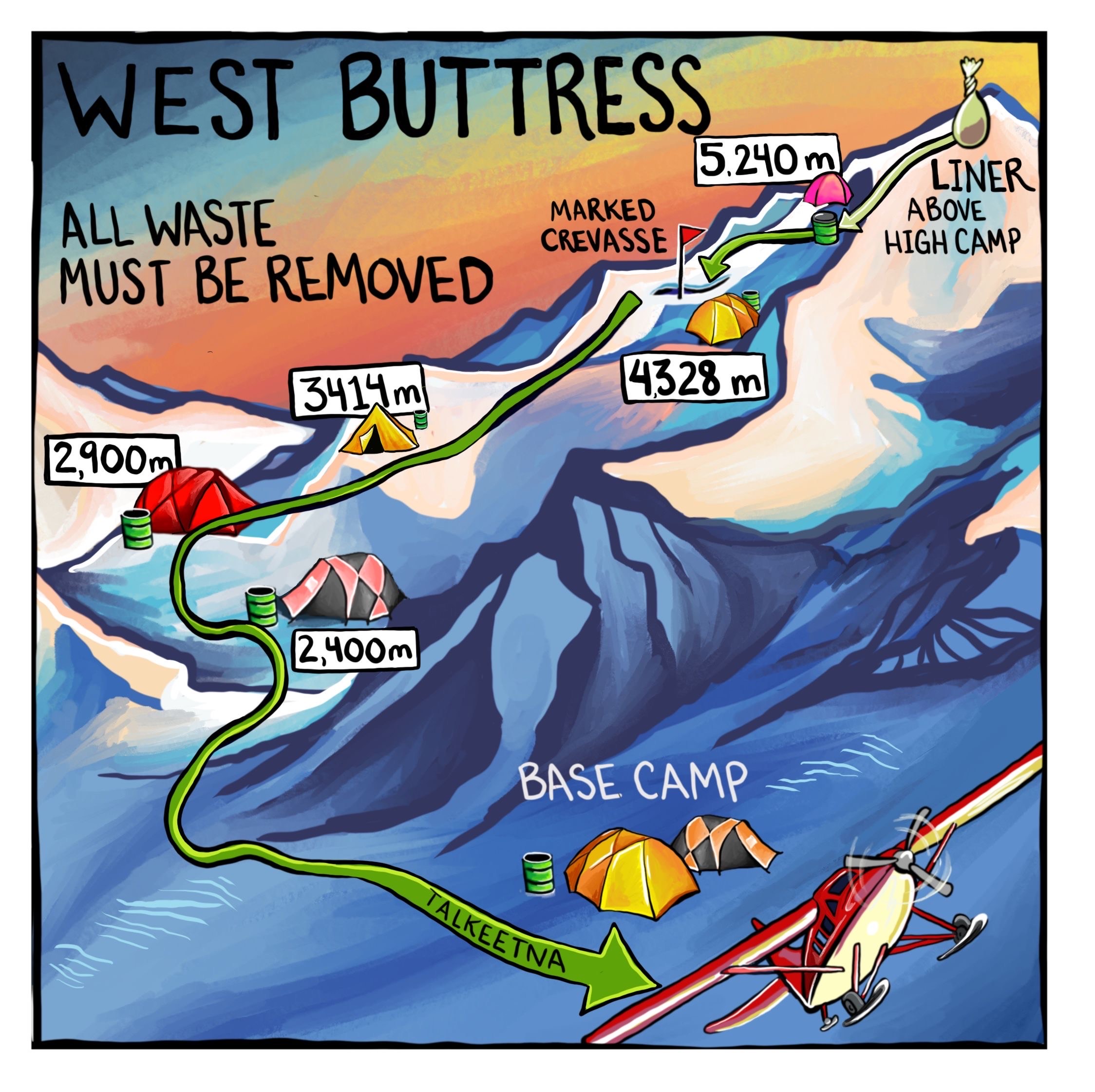

Picture 1 “A current overview of human waste removal from the West Buttress. Below 14,200’, or 4,328 meters, all waste must be carried back to Talkeetna in CMC’s. There is a large crevasse at 14,200’, marked by the NPS, in which waste can be deposited by private expeditions.” (NPS Graphic/Sarah Glaser)

The first recorded mention of trash on Denali comes from Hudson Stuck’s book, “The Ascent of Denali,” describing their historic ascent to the South Summit in 1913: “We came upon the vestiges of a camp made by our predecessors of a year before, in a hollow dug in the snow—an empty biscuit carton and a raisin package, some trash and brown paper and discolored snow—as fresh as though they had been left yesterday instead of a year ago.” The conditions in the Alaska Range do not lend themselves to breaking down any type of waste; the only sure way to remove trash is by taking it out of the mountains all together. If you multiply the scenario described by Stuck by a hundred or so years and thousands of climbers, you can imagine what we might be dealing with. In recent decades, built up detritus from past expeditions have necessitated organized clean ups in areas from the Kahiltna to the Muldrow.

Given that we must melt snow for drinking water on the mountain, human waste has been particularly troublesome in the past. Consider Jonathan Waterman writing of having to “select cooking snow very carefully from among the wasteland of brown turds.” Or this description in a 2002 AAC publication of what a toilet up at high camp was like before the current waste management program: “the toilet overflows during storms and extended rescues when rangers are not able to service it.” So, you can understand why Roger Robinson was particularly passionate about this issue over his storied career, which began in 1980.

Denali Mountaineering Ranger Roger Robinson cleans up trash at Windy Corner (13,000 feet)

22 years ago, Roger decided enough was enough and dreamed up the CMC. This system and its implementation have changed the climbing experience on the West Buttress for the better and won Roger many accolades. From the NOLS Fall 2003 Leader celebrating a Stewardship Award from the school: “Since 1980, Roger has been a Mountaineering Ranger for Denali National Park. Roger is passionate, practical, creative, and thorough in his approach to teaching and implementing Leave No Trace ethics in a mountaineering environment. His commitment to Denali National Park extends back to 1975, when, prior to working for the Park, he participated in early “clean-up climbs.” In 2000, Roger convinced the Park Service to allow him to implement the “Clean Mountain Can” project to remove human waste from Mt. McKinley. With cooperation and support from organizations such as the American Alpine Club, the Access Fund, and Geo Toilet Systems, Roger and the Denali Ranger team designed a small, light version of a commercial river toilet box for climbers to use during their summit of Mt. McKinley.”

Picture 2 and 3 “What goes in my CMC? A few simple do’s and don’t’s” (NPS Graphic/Sarah Glaser)

Picture 2 and 3 “What goes in my CMC? A few simple do’s and don’t’s” (NPS Graphic/Sarah Glaser)

Roger first tested this system on many of his own expeditions, and began to gain traction convincing others to try it as well. In 2006, CMC use became compulsory. There were changes to the can to make it easier to clean, and the color changed from gray to green. That season also marked the removal of latrines at both the Ruth and Kahiltna base camps. Late season melt out at both locations revealed very old waste that hadn’t broken down, and it seemed like it was time for a change. These latrines had been in use since 1977 (see 2006 season summary for more information).

In 2018, the Park Service began requiring a full pack out from 14,200 feet to Basecamp on the West Buttress. Around that same time, most guiding companies began removing waste from the entirety of the West Buttress, most likely because they have seen the effects first-hand of not packing out your waste.

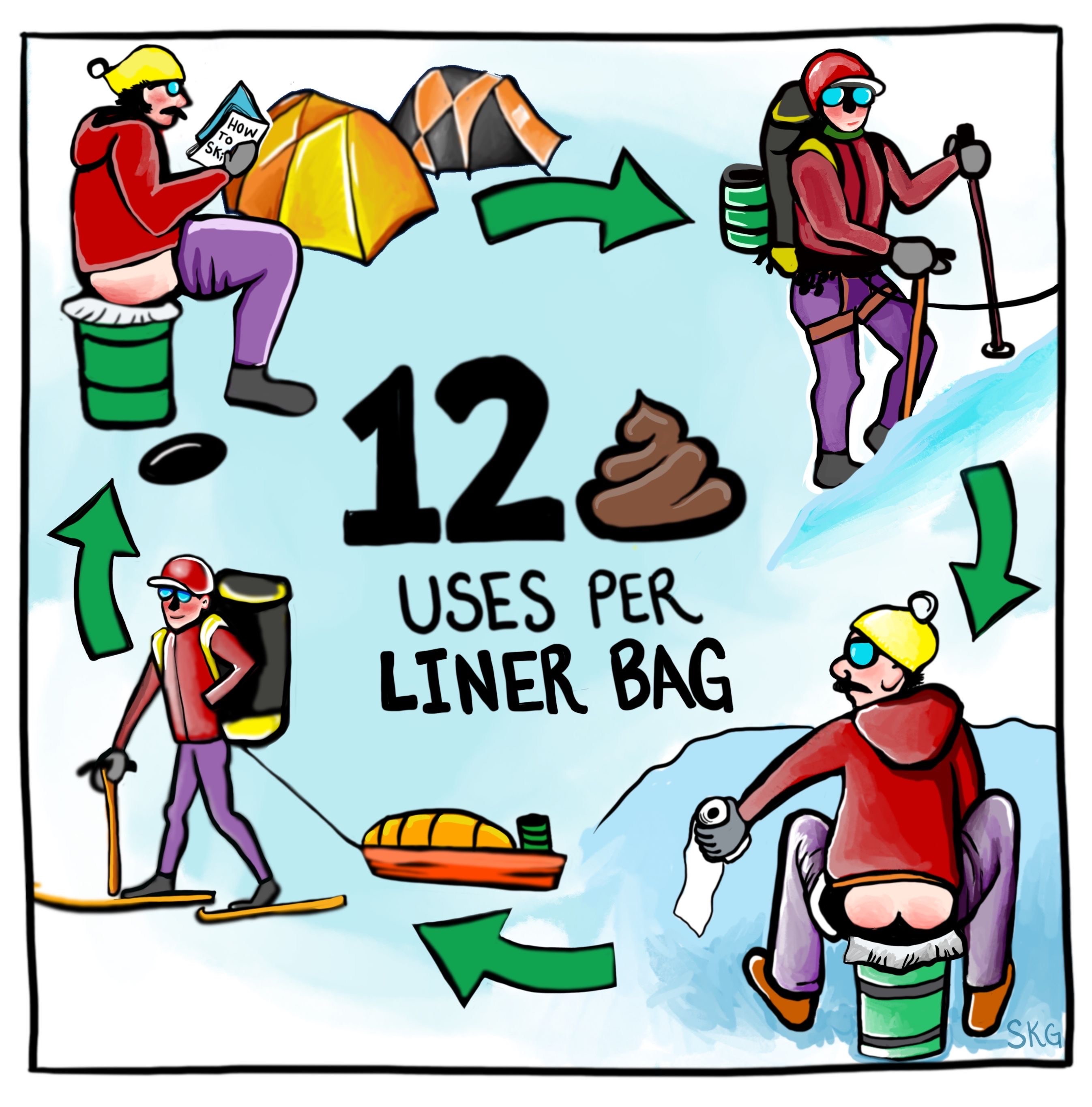

Picture 4 “12 poops per can x 5 people x 21 day expedition = how many cans…? At the Talkeetna Ranger Station, we understand that we’re all climbers, not mathematicians. Come on in and we’ll help you figure it out.” (NPS Graphic/Sarah Glaser)

One of the challenges of the CMC program is communicating to climbers how to correctly use them. This can be particularly difficult for foreign climbers who do not speak English, and understandably may be a bit lost in the deluge of information when they come to our in-person briefings. To solve this problem, we enlisted the help of local Alaska artist Sarah Glaser to make us some illustrations on how to use the CMC’s. The hope was that people could look at these without speaking a word of English and understand how to properly manage human waste. We liked her illustrations so much that we enlisted her help again to create some diagrams of other safety systems and problem areas on the mountain. We are excited to see what she comes up with soon!

Picture 5 “Hot tips for keeping poop off your stuff.” (NPS Graphic/Sarah Glaser)

It’s been quite the journey over Denali’s recent human history, but these are just some of the ways in which we’re tackling the human waste problem up there. One thing is for sure, Roger Robinson and the CMC program has made a huge impact on our success.

References

“Awards: Roger Robinson.” The Leader. Fall 2003.

O’Neil, Michelle, et al. “Trash Monitoring and Human Waste Study 2001.”

Robinson, Roger. “Update for the 2002 Denali Climbing Season.” AAC Magazine. 2002.

Stuck, Hudson (1918). The Ascent of Denali. Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Waterman, Jonathan (1997). Surviving Denali. The AAC Press.

|

April 21, 2022

|

Last updated: April 21, 2022