Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons Why a Stone Fort?St. Augustine’s first 100 years were plagued by poverty and pirate attacks. Beginning in its founding year of 1565, nine wooden forts were built one right after the other as rot, termites, storms, tides, and fires destroyed the fragile structures. After years of petitions, a devastating raid in 1668 convinced the Spanish crown that La Florida truly needed strong defenses. English pirates under the command of Robert Searle, also known as John Davis, attacked the town, killed 60 people, looted every building, and ransomed 70 more people for food, water, and firewood. The pirates also measured the inlet’s depth and took careful notes of its latitude and landmarks, intending to come back and seize St. Augustine and its rotten wooden fort to make it their base of operations.

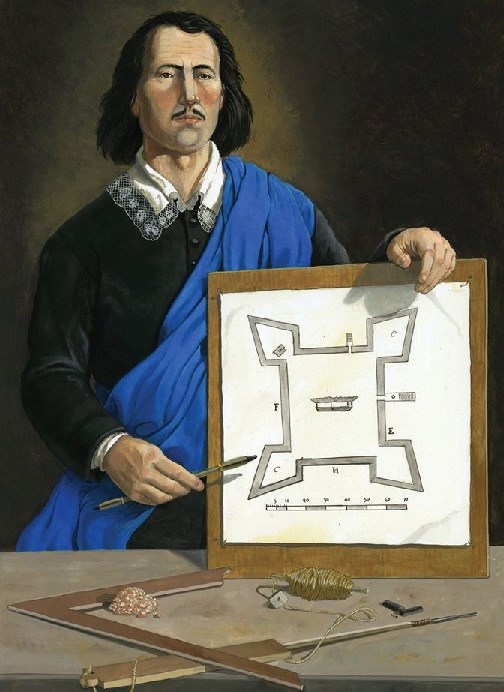

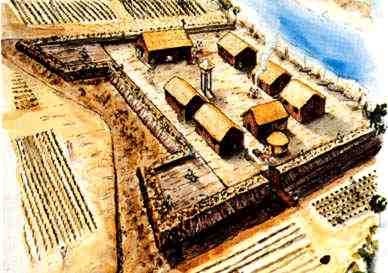

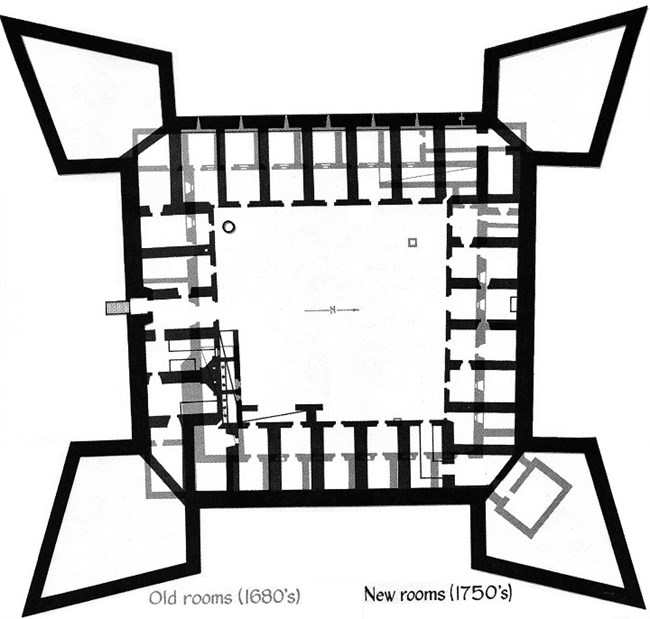

Royal OfficialsDon Manuel de Cendoya, who was appointed governor of La Florida after nearly 21 years of service to the crown, arrived in St. Augustine in July of 1671 and immediately went to work on preparations for construction. Engineer Ignacio Daza arrived from Havana a year later and set about designing the fortification. On the afternoon of October 2, 1672, the governor and his officers raised shovels to break ground on the ambitious project. Five months later, both Cendoya and Daza were deceased, likely victims of a winter illness. They had seen the Castillo’s eastern wall and bastions raised to a height of 11 feet. Over the next 23 years, six different governors struggled against changing plans, financial setbacks, epidemics, storms, starvation, pirate attacks, and lack of royal support. It was not until August of 1695 that the Castillo was declared finished, under the supervision of Laureano de Torres y Ayala. In the end, the project on which Cendoya had planned to spend about 70,000 pesos totaled at least 138,375 pesos, approximately $2,845,000 in 2020 U.S. dollars. Cendoya himself had sunk so much of his own salary into those first years of planning and construction that it took his widow, Doña Sebastiana Olazarraga y Aramburu, 10 years to collect what was owed to him, years during which she and her children were forced to live on the charity of St. Augustine’s residents. Native AmericansLocal Native tribes made up the largest group of laborers at the Castillo. Three nations — the Guale (from coastal Georgia), Timucua (from North Florida) and the Apalache (from the present-day Tallahassee area) — were forced into service. Although there are records indicating they were paid and fed, there are also records that alleged the Spanish authorities mistreated the Natives. Franciscan friar Alonso del Moral accused authorities of forcing Natives to work "without paying them that which is just for such intolerable work." They were forced to collect oyster shells, demanding work that led to painful lacerations that were highly susceptible to infection. Others were forced to dig foundation trenches, which was tedious backbreaking work. Native families began to suffer as the men were conscripted and had to travel long distances from home, leaving the women to feed and care for children on their own. In theory, each complement of Native labor served only a certain length of time. In practice, it was common for the men to be held long past their assigned time. At times, as many as 300 Natives served the crown in St. Augustine, either working on the Castillo or planting, cultivating, and harvesting large fields near the city. The maize (corn) they were forced to grow was the staple food issued to Native laborers and sometimes to Spanish convict laborers if flour from Spain was not available.

The Natives were paid 1 real per day (approx. $2.57 in 2020 USD) for the difficult labor of quarrying and moving stone. Some of them developed the skills of carpenters, for which they were paid 8 reales. One man, named Andres, worked on the Castillo as a stonecutter for 16 years. Throughout the entirety of the fort’s construction, European diseases for which the Natives had no immunity wreaked havoc on the workforce. Every few years, El Contagio — the Contagion — resurfaced and decimated their ranks. Before the Spanish arrived in the 1500s, there were hundreds of thousands of Guale, Timucua, and Apalache in the Southeast. Those who survived disease and conquest were forced to adapt, change, and eventually assimilate their culture with the Spanish or with other indigenous cultures which were dislocated from their traditional life ways. Over time, these people contributed to the foundation of the Seminole and are represented by them to this day. Few Natives would benefit from their peoples’ sacrifices to construct the fort. African LaborAfricans both free and enslaved made up portions of the Castillo’s labor force, as they had always made up portions of St. Augustine’s population. The Spanish system of slavery allowed for enslaved people of all ethnicities to gain their freedom through self-purchase or service to the crown, and so a class of free blacks existed alongside their enslaved counterparts in Spain as well as all of her colonies. Due to St. Augustine’s small population, relative poverty, and lack of plantation industry, there were few enslaved Africans in the city, and most of them were held by wealthy government officials. For the hard manual labor of fort construction, both Governor Cendoya and his successor, Sergeant Major Nicolás Ponce de León, suggested importing 30-50 enslaved Africans from Havana, but it’s unclear whether their requests were ever granted. In 1687, 18 enslaved Africans belonging to the Spanish crown joined the labor force.

Once St. Augustine had royal endorsement of its reputation as a place where the enslaved could become free through service and loyalty to the crown, more and more fugitives made the perilous journey. Two new edicts issued in 1733 forbade any compensation to the British, reiterated the offer of freedom, prohibited the sale of fugitives to private citizens, and stipulated that they would be required to complete four years of royal service prior to being freed. After that, so many Africans escaped enslavement in Carolina that Governor Manuel de Montiano chartered a settlement for them two miles north of the city; Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose, commonly known as Fort Mose, was established in 1738. In addition to serving in a militia to defend St. Augustine, the men of Mose would have worked on the Castillo during its renovation phase, which also began in 1738. Craftsmen, Convicts, and CiviliansThe rest of the Castillo’s labor force was made up of a diverse combination of men from different backgrounds, races, and situations. Professional artisans included masters of construction, stonemasons, stonecutters, and carpenters who came from Cuba, Spain, and even the Carolina colony. In 1670, Englishmen captured on a vessel near the Savannah River were brough to St. Augustine as prisoners. Three of them were masons, and they were soon enlisted to help build the Castillo. Stonecutter William Carr (known in Spanish as Guillermo Car) eventually converted to Catholicism, married a Spanish woman, and enlisted in the Overseas Troops as a gunner. John Collins (or Juan Calens) was a skilled lime burner who was eventually promoted to quarry master and even defended royal property at the quarry when English pirates attacked in 1683. A 1679 roster listed seven black and mixed-race men among the convict laborers. A typical convict might have been a Spanish citizen caught smuggling English goods into the colony; he was condemned to six years’ labor on the fortifications. Local Spanish “peons” (paid 4 reales per day) and even the soldiers worked on the Castillo over the years as money and labor shortages slowed progress.

A Monument to Conquest, Ingenuity, or Diversity?The Castillo de San Marcos took a heavy toll on the lives and cultures of Florida's Natives as disease and conquest devastated their population. When the ingenious structure was declared finished in 1695, it would have looked different than it does today. Renovations began in 1738, were interrupted by the British siege of 1740, and were finally completed in 1756. Once again, the construction crews endured remarkable hardships and represented all walks of life to be found in the city: professional engineers and craftsmen from Spain and her colonies, Africans both free and enslaved, citizens born of Native American and European parents, soldiers, and even the governors. Conflict among the different groups of laborers slowed construction on occasion, but they were still able to come together and work towards the common goal of protecting their home. Castillo de San Marcos is a reflection of the diverse peoples who toiled together to construct a never-defeated fortress. Today, visitors and community members alike help carry on the tradition of protecting the city's history and celebrating our own diversity. |

Last updated: June 26, 2023