NPS Photo/Peter Densmore What words come to mind when you think of different kinds of fire? The community of being around a campfire? The destruction that comes with a house fire? Perhaps the usefulness of a prescribed burn? There are many different ways that we can think of fires. While plant communities in the western United States have had plenty of time to adapt to natural fires, adaptation has often been more challenging for the communities of people living in these same spaces. Humans have a complex and dynamic relationship with fire, and our changing attitudes over time are reflected in how our fire management policies have changed. Recent Major Fires

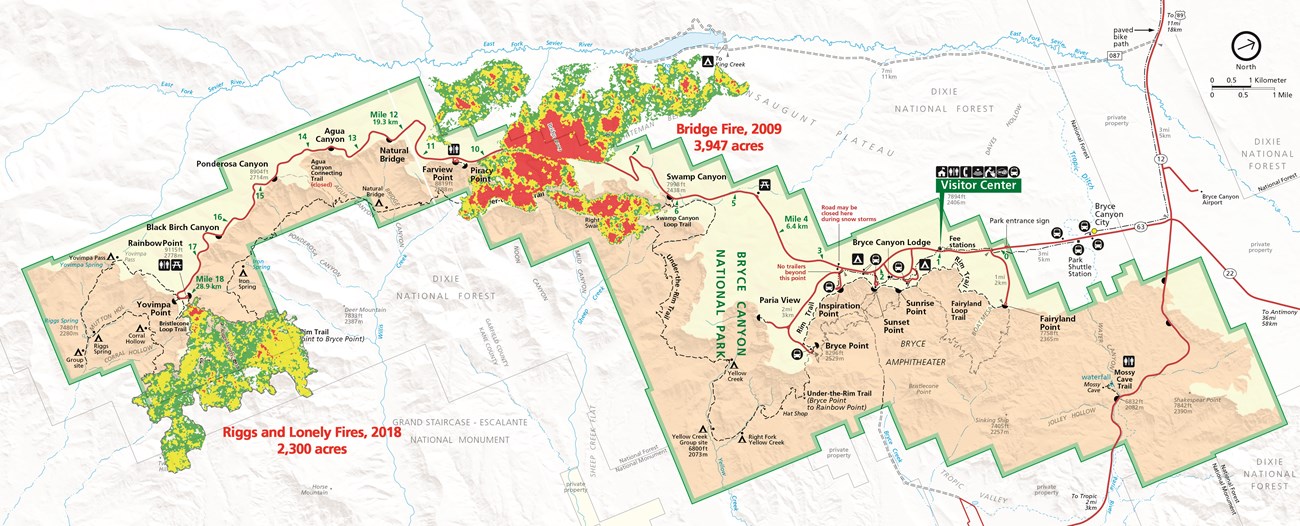

NPS Photo Bridge Fire (2009)The Bridge Fire started from a lightning strike on June 14, 2009 at Bridge Hollow in Dixie National Forest land. Following the lightning strike, the fire was closely monitored and managed so that it could provide resource benefits, like reestablishing quaking aspen and ponderosa pines, and reducing fuel loads resulting from fire suppression. One month later, on July 14, hot and dry conditions along with unpredictable winds from the southwest carried the fire into the park. 30 mph (48 km/hr) gusts carried sparks from the flames across the scenic drive near Whiteman Bench, allowing the fire to spread quickly.

NPS Photo Riggs and Lonely Fires (2018)Both the Riggs and Lonely Fires were started by lightning strikes – the Riggs Fire on August 25, 2018, and the Lonely Fire on September 6 of the same year. Both of these fires originally started on Dixie National Forest land, and eventually merged into one large fire in mid-September. The area in which the fires were burning hadn’t been impacted by fire for many years, so fire managers decided to let them burn naturally to reduce the buildup of fire fuel brought on by fire suppression. At one point, however, the fire began to spread up into the park towards the parking lot by Rainbow Point, which would threaten both visitors and historic buildings like the restrooms on the south side of the parking lot. As a result, fire managers decided to implement a backburn off of the Bristlecone Loop trail. How Do We Learn From Our Fire History? Both the Bridge Fire (2009) and the Riggs/Lonely Fire (2018) began with lightning strikes. However, the Bridge Fire was the main reason the Riggs/Lonely Fire wasn't as severe as it could have been. After a fire, managers will reflect on what they could have done better. Following the Bridge Fire, this reflection led to the implementation of the fuel reduction program at Rainbow Point. Although lightning-caused fires can be unpredictable, we can use the past to plan ahead and prepare ourselves for the future.

What other lessons have we learned? Continue reading for a brief history of fire in the National Park Service, or check out the NPS Interactive Wildfire History Timeline!

NPS Photo Historic Fire RegimeBefore European colonization of the Americas, many indigenous peoples utilized controlled burns. These fires modified the landscape, helping to maintain the habitats of animals and plants that sustained their cultures and economies. However, as indigenous peoples were displaced by colonists and killed off by European diseases, attitudes towards fires began to shift. Rather than a helpful tool, fire was seen as a threat and feared by European colonists. As a result, fire suppression became a widespread policy. By 1911, with the passage of the Weeks Act, native fire practices were largely made illegal. Why the move away from complete suppression? By the 1920s, the Forest Service had determined that fire had no place in the forests. Thus began the “10 a.m. Policy”. This required all wildfires to be completely suppressed by 10 a.m. the morning after they were first spotted, or as soon as possible after that.

Initially, fire suppression was seen as very successful. In the 1930s, about 30 million acres of forest burned per year. This was reduced to only 2-5 million acres per year by the 1960s. However, there were dissenters throughout these years. Scientists and naturalists argued that fire played an important role in many ecosystems. Like the fires, these voices were mostly suppressed until the late 1960s and 1970s. By this time, research was beginning to show the effects of fire suppression, including the buildup of fire fuel. Other research argued that fire was necessary to reestablish populations of some plants, like the giant sequoia, because their cones could only release seeds if they were first burned in a fire. In the 1960s, the National Park Service began to deviate from Forest Service policies. A special advisory board on wildlife management released the Leopold Report in 1962, which stated that “parks should be managed as ecosystems”. Furthermore, the Wilderness Act of 1964 encouraged parks to allow for natural processes, including fire. By 1968, the National Park Service changed its policy to recognize fire as an important ecological process. Fires are now allowed to run their natural course as long as they fulfill approved management objectives. Want a more in-depth timeline of wildland fire history? Check out the NPS Interactive Wildfire History Timeline!

|

Last updated: April 4, 2024