Welcome to Hopedale, one of six sites that make up Blackstone River Valley National Historical Park. Hopedale is a planned community with a complex history.

People have lived in this area for thousands of years. One of the sources for life that connects us to the people of the past is the Mill River. The Indigenous people of this place are the Nipmuc, and they are still here.

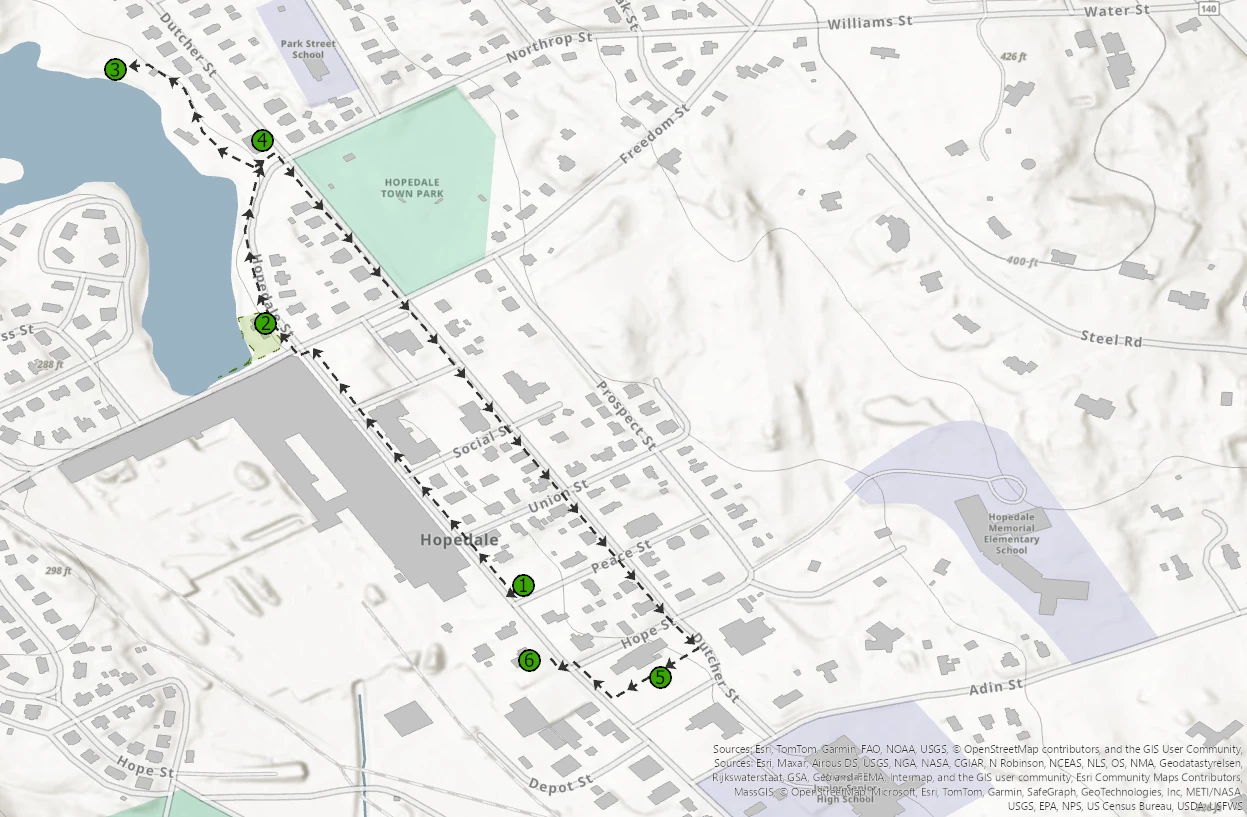

The land that comprises Hopedale was once part of the town of Mendon. English colonists, including Benjamin Albee, came to the town in the 1660s to settle and run small industries. In July 1675, Albee became a casualty of King Philip’s War. After Albee’s death, some colonists left the area. In the decades after the war’s end, retreat was not the general trend among the colonists. Newcomers continued to encroach on Indigenous lands. Gradually, this area became a settlement for colonial farmers. Through the 1830s, a few thousand people made their living in Mendon. People were industrious, working in homes and small shops, but there was scarcely a hint of large-scale industry. Enter local minister Adin Ballou. Together with a group of like-minded people, Ballou purchased hundreds of acres of land around this area in 1842. This decision would change the course of history in Mendon. In Adin Ballou Park, a statue of Hopedale's founder presides over a beaten front doorstep and boot scraper. These relics of the commune era come from the Jones homestead, where early Community members held meetings. The Jones farmhouse was the “home base” for the Hopedale experiment. After crossing over that threshold, Ballou and others made their plans to build commune from the ground up. These kindred spirits (who believed in abolition, temperance, and equality of the sexes) imagined that others would want to make Practical Christian communities, too, and that they could all transform the world. Together, they worked hard to make “Fraternal Community No. 1” a reality. Ballou’s own house was once on this land. This is where he wrote his sermons and worked on The Practical Christian, the Community paper. The Ballou house was moved to Bancroft Street in 1900, and this statue was put in its place. The home still stands, but it is a private residence today.

The Little Red Shop is a museum dedicated to preserving the history of the Town of Hopedale and the legacy of the Draper Corporation. Originally, the shop was located on the opposite side of the millpond. It was moved to this location in 1951.

Ebenezer D. Draper, one of the members of the 1840s community, used this building as a machine shop. His team of workers produced parts for mechanical weaving looms (machines that make cloth). These colleagues were among the industrious followers of Adin Ballou. During the heyday of the commune era, this shop was once surrounded by other homes and buildings all made by, for, and within the community. From 1842 through the early 1850s, shares in the community were distributed to its members to give everyone an equitable say and portion of the profit. During that time, Ebenezer Draper was among the most successful members of the commune. Some of this came from his own hard work; but Draper also inherited some of his good fortune. Draper’s father, Ira, had secured a patent on a device that saved weavers time and provided better control over cloth on the loom. In 1853, Ebenezer’s brother George Draper joined the Community. He devoted considerable energy to finding new and improved ways to mechanize the weaving process. The Drapers’ business became a main source of support for the communal association, eventually earning the family a controlling portion of the communal shares. In 1856, the Draper brothers purchased the community and assumed its minimal debt. This action would change everything. George Draper gave rise to a new era in Hopedale. This Draper brother had a passion for finding innovative technology to make the production of cloth more efficient. He led the company's charge to become the nation's leading producer of machines for the cloth-making industry. The more idealistic Ebenezer, who had started the business as a member of the original Hopedale community, eventually left town. For him, finances came second to the fraternal order. Even without Ebenezer, the Drapers ran one of the most successful textile production companies in the world. Although their business got its start in the Little Red Shop, the Drapers’ ambition quickly outgrew their small, unassuming workshop. Over time, new buildings were constructed all over Hopedale, including a large brick complex that eclipsed all others in town. During the 1880s, Draper produced and sold more than six million new high-speed spindles to textile companies. By the 1890s, the Drapers dominated the nation's loom-making business. Workers in Hopedale manufactured every piece of the machines they used, including the nuts and bolts. Some processed raw steel in the foundry. Other laborers innovated and made new technologies, such as the bobbin battery, that would change the weaving world. At its height of production, the Draper Corporation employed more than 4,000 workers. For many years, their home base was a massive facility located opposite the present-day Draper museum. Many community institutions were built with money from the Draper business. But this era of prosperity did not last forever. After World War II, the Draper family slowly divested themselves of most of their town properties. The corporation was also acquired by an outside owner, Rockwell International. They closed the large plant on Hopedale Street in 1978. After decades of vacancy, demolition of the Draper complex began in August 2020 and continued through 2022. During your visit, you may see some signs of the factory that was once here. Most visitors will have to imagine what this huge presence was once like, however, in the space of its vacancy. Welcome to the Hopedale Parklands. This 200+ acre park contains miles of maintained trails, an old bath house, and plenty of trees. It is free and open to all.

When the early Hopedale residents came to this area to start their commune, they almost immediately started planting trees. Creating a healthy, green landscape was important to them. As Hopedale became a company town, the leaders within the community started to think differently about open space. Nothing would be left to chance. They wanted a plan for their recreation. The land for the Hopedale Parklands was set aside during the height of the Drapers’ industrial growth in Hopedale. Warren Henry Manning, who had helped develop Boston's regional park system, designed this public park to encircle the pond. Manning was also part of the planning process for creating workers’ homes around Hopedale Pond. At one time, every Hopedale resident had a connection to Drapers—even if they did not work for the company. While investing some of their wealth back into the community, the Drapers sponsored events such as field days. While the Draper factory no longer stands, residents and visitors can still enjoy the Parklands and appreciate Hopedale Pond. Before leaving this park, take a moment to enjoy the relative quiet of this landscape. What creatures are enjoying the Parklands today? Hopedale began with a series of meetings in a single home, the Jones Homestead. Within a half a century, Hopedale was known for its large, luxurious worker housing. How did that happen?

For decades, the Drapers sought to keep workers local by constructing quality housing in Hopedale. Today, one of the most lasting legacies of the Draper Corporation is the collection of award-winning, internationally recognized homes commissioned by the company to fill up the town. Unlike other multi-family units in nearby communities, these Draper homes are designed to do more than meet basic housing needs. These were designed to impress. In particular, the Dutcher Street duplexes were built to be considerably larger and more elaborate than most multi-family housing units constructed in the Blackstone Valley. These houses are yet another tangible link to the Draper era. They remind us that there were clear benefits to having a high-paying job in Hopedale. Everyone living in these Draper homes could enjoy their time off in beautifully maintained green spaces. They also had access to a group of workers assigned to provide regular maintenance. In addition to that support, the Drapers implemented efficient system of garbage collection and constructed a sewage system that was connected to every house in town by the late 1890s. All houses had water, gas, electricity, and indoor plumbing by 1910. Was there a downside to living in Hopedale? People who chose to reside in this company town had less privacy than residents in more rural areas. All of the yards for these homes were highly visible as well as interconnected. Skilled workers who opted to stay with Draper would have had few hard and fast boundaries between their work life, their home life, and their recreation in town. Notably, not all Draper employees lived in Hopedale, or had the same access to these privileges. The Prospect Heights section in nearby Milford was also home to Draper employees, many of whom were recent immigrants to the United States. Those residences were more typical of what a wage earner in a factory could expect from employee housing. During this part of your tour, you will see three kinds of community spaces: a church, a town hall, and a recreation center. Consider whether the places where you like to worship or have fun. Are they connected to your work life?

In many company towns, business leaders also invested in churches, or other religious spaces. For some in Hopedale, everything may have felt connected to work, or at least, the Draper family. The Unitarian Church across from Town Hall was erected in 1898. It was designed as a memorial to George and Hannah Draper by their sons, George and Eben Draper. Half a century before, the Community members in Hopedale had worshiped in close proximity to the early Draper shop, close to the millpond. By 1900, people in Hopedale would no longer use any of the early Community buildings, such as the church or library. Instead, they would worship in a Draper-financed church next to or across from a town building and factory complex all bearing some relationship to Draper family. As the Drapers’ wealth grew, their power in Hopedale and throughout the state also increased. Eben Draper served as Governor of Massachusetts from 1909-1911. Other Drapers distinguished themselves through military service and philanthropy. For his part, George A. Draper, who always kept a close eye on Hopedale, presented the Town Hall to the residents in 1887, one year after Hopedale was granted township. The building (which still stands today) was designed to accommodate businesses on the ground floor and has an auditorium on the second floor.The Hopedale Community House is yet another link to the company town era. The large recreation center (and accompanying Draper Gymnasium) are managed by a private, non-profit organization, Hopedale Community House, Inc. These buildings were given by the Drapers in 1922. Just a few years prior, Hopedale had been in turmoil. In 1913, a worker-led strike left Hopedale in crisis for months. Workers were bitterly divided as to the merits of unionizing, and one worker was fatally shot by hired police during the conflict. Following this event, leaders in the Draper family and business chose to invest in more company-sanctioned spaces. There were many benefits to having a new town hall, a new place to worship, and places to relax such as the Hopedale Parklands and the Community House. Yet all who stepped foot into these areas knew that they had a thread leading back to the factory. The company and the town were woven together for many who resided here. No one living in Hopedale today works to produce looms on a large scale. However, the people who labored in the Draper Corporation buildings have left a lasting impression through these buildings. With their hard work and dedication, they made machines that transformed the production of cloth around the world. For some, decades of commitment to the Drapers also meant having beautiful places for members of the family to pray and play, very close to home. This building was donated by Joseph Bancroft, a member of the original Hopedale Community. It is fitting to end your visit with Mr. Bancroft, who not only experienced the change from commune to company town, but learned to thrive in both.

In 1856, Bancroft cast the lone vote against the dissolution of the community. Though he may have been dissatisfied with the Drapers’ decision to change the structure of the Community, he stayed and built a life in Hopedale. In fact, Bancroft remained a life-long friend of Adin Ballou and became a business partner of the Drapers. With a strong interest in improving community life, Bancroft provided the money to build this distinguished building, which he dedicated to his wife. The library sits on land that is very close to the site of Adin Ballou’s first home in Hopedale. Initially, Ballou and his followers had come to this place to break away from society and create a model community. The Practical Christians were not alone in feeling disillusioned with society in the 1840s. Elsewhere in Massachusetts, Henry David Thoreau withdrew to his cabin on Walden Pond to live out his values alone, while Transcendentalists such as Ralph Waldo Emerson and Bronson Alcott experimented with communal living. The original Hopedale community was the most enduring of these communal societies, outliving the better-known Brook Farm by a decade. Its absence in many history books might be explained by the long shadow cast by the Draper company. While this tour began with a statue of Ballou, it ends with “Hope,” an art piece located outside of the library. Susan Preston Draper presented the elegant white marble statue in 1904. Despite all of the major changes that have affected Hopedale over the last two centuries, this is perhaps the most lasting thread: the idea of hope, of building something that will last for future generations. Today, the Bancroft Memorial Library is an excellent community resource and an important Hopedale archive. It houses a small collection of artifacts and memorabilia, including Adin Ballou's cradle and writing desk, as well as portraits of Hopedale's founders. It is one of the places in the community where the past is still present.

|

Last updated: April 30, 2025