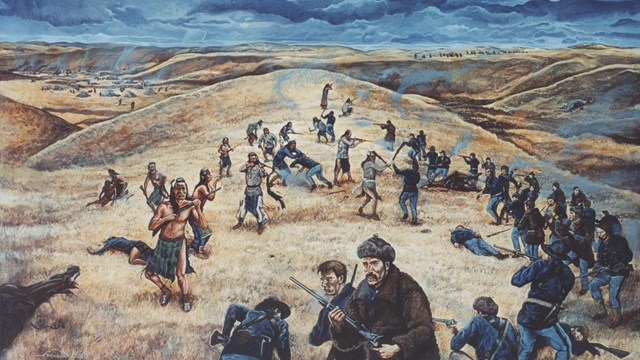

NPS The Battle of Big Hole: A Historic Moment in the Nez Perce Flight of 1877Big Hole National Battlefield marks the site of the battle that occurred on August 9 and 10 during the Nez Perce Flight of 1877. In early August, over 800 nımí·pu· (Nez Perce), and more than 2,000 horses, traveled peacefully through the Bitterroot Valley after crossing Lolo Pass into Montana. Their leaders believed the military would not pursue them into Montana, despite many having premonitions that suggested otherwise. When the nımí·pu· arrived at ?ıckumcılé.lıkpe (known today as Big Hole National Battlefield) on August 7, they were unaware that the military was close behind them. U.S. troops launched a surprise dawn attack on the sleeping nımí·pu· encampment on the morning of August 9. Key Moments in the Battle of Big HoleExplanation of the Numbers: The numbered sections outline significant phases of the Battle of Big Hole during the Nez Perce Flight of 1877: Official Big Hole National Battlefield Map and BrochureThe official brochure and map for Big Hole National Battlefield is available in several formats by visiting our Park Brochure page. 1. Nez Perce Camphímı.n maqsmáqs (Yellow Wolf) described that night: “The warriors paraded about camp, singing, all making a good time. It was the first since war started. Everyone with good feeling. Going to buffalo country! . . . War was quit. All Montana citizens our friends.” Meanwhile Colonel John Gibbon reported “All laid down to rest until eleven o’clock. At that hour the command . . . of 17 officers, 132 men and 34 citizens, started down the trail on foot, each man being provided with 90 rounds of ammunition. The howitzer [cannon] could not accompany the column. . . . Orders were given . . . that at early daylight it should start after us with a pack mule loaded with 2,000 rounds of extra [rifle] ammunition.” 2. U.S. Military Attackshú.sus ? ewyí.n (Wounded Head) told what happened before dawn August 9: “A man . . . got up early, before the daylight. Mounting his horse, he . . . crossed the creek, when soldiers were surrounding the camp . . . he was shot down. The sound of the gun awoke most of the band and immediately the battle took place.” Corporal Charles Loynes recalled, “We received orders to give three volleys [low into the tipis], then charge—we did so. That act would hit anyone, old as well as young, but what any individual soldier did while in the camp, he did so as a brute, and not because he had any orders to commit such acts.” 3. Warriors Drive U.S. Military Back“These soldiers came on rapidly. They mixed up part of our village. I now saw [tipis] on fire. I grew hot with anger,” recalled hímı.n maqsmáqs (Yellow Wolf). “Those soldiers did not last long. . . . Scared, they ran back across the river. We followed the soldiers across the stream. . . . the soldiers hurried up the bluff.” Amos Buck, a civilian volunteer, told: “Here we began to throw up entrenchments. The Indians quickly surrounded us and were firing from every side, while we were digging and firing.” 4. Warriors Capture Army HowitzerColonel Gibbon recalled: “Just as we took up our position in the timber two shots from our howitzer on the trail above us we heard, and we afterwards learned that the gun and pack mule with ammunition were . . . intercepted by Indians.” wewúkıye?ılpílp (Red Elk) also described the capture: “We saw the warriors closing in on the cannon. Three men, one from above and two below . . . None of the three stopped from dodging, running forward. The big gun did not roar again.” 5. Warriors Besiege SoldiersSome warriors kept the soldiers and volunteers besieged while others raced back to camp. “I started back with others to our camp,” explained hímı.n maqsmáqs (Yellow Wolf). “I wanted to see what had been done. It was not good to see women and children lying dead and wounded. . . . The air was heavy with sorrow. I would not want to hear, I would not want to see again.” 6. Surviving Nez Perce Familes FleeThe nımí·pu· buried their dead and prepared to move. Most warriors went with the camp to protect it. The battle continued and some warriors stayed behind, including hímı.n maqsmáqs (Yellow Wolf), who told: “The night grew old and the firing faded away. Soldiers would not shoot. . . . We did not charge. If we killed one soldier, a thousand would take his place. If we lost one warrior, there was none to take his place.” Near dawn they saw a man ride up to the soldiers. “We did not try to kill him. . . . The soldiers made loud cheering. We understood! Ammunition had arrived or more soldiers were coming. . . . We gave those trenched soldiers two volleys as a ‘Good-by!’ Then we mounted and rode swiftly away.” AftermathThe battle at Big Hole was a turning point in the Flight of 1877. The nımí·pu· no longer considered "all Montana citizens our friends." Between 60 and 90 nımí·pu· men, women, and children were killed during the battle, with an unknown number wounded, some killed or injured by Bitterroot civilians who the nımí·pu· recognized. Of the military and civilian volunteers, 31 were killed, 38 wounded. After the battle, the nımí·pu· fled south, crossing back into Idaho over Bannock Pass, before heading east towards Yellowstone National Park. They attempted to avoid towns and ranches, but when they did encounter settlers, the nımí·pu· no longer trusted them. The military caught up to the nımí·pu· for the first time after this battle on August 20 at Camas Meadow, west of Yellowstone National Park. Learn more about what happened next by following the links below.

Directions to Big Hole

Directions to the Big Hole National Battlefield.

Camas Meadows History

The Nez Perce were able to steal more than 200 of the Army's pack horses and mules, halting the Army's advance during the Flight of 1877.

The Nez Perce Flight of 1877

In 1877, the non-treaty Nez Perce were forced on a 126-day journey that spanned over 1,170 miles and through four different states. |

Last updated: February 27, 2026