Nicoletta Browne, NPS You can learn more about the plant communities that these species belong to here, and use this page to learn more about the plants as you observe them. Note that not every single species may be present or noticeable along the trail (or in the monument) at a given time. You can also visit this page to learn more about the Heritage Garden located nearby, which seasonally features Pueblo crop varieties similar to those that were grown here in past times. All photos on this page are courtesy of SEINet Arizona-New Mexico Chapter, except as noted. Their database for Aztec Ruins National Monument can be visited here. How To Use This GuideThe plants of this guide are organized alphabetically by common name, according to the sections "shrubs" and "trees". Although this guide is organized by common names, often it is easier to distinguish a species of plant by its latin name because there can be many common names for one species of plant. Another note is that the Native Plant Trail represents a group of plants that are found within different ecosystems in this landscape and won’t necessarily be found in an ecozone that they are not ecologically adapted for. An example of this would be plants found in the riparian zone such as willow, which will not be growing in areas of the semi-desert shrub step zone with sage brush and yucca without ample water present.As the Natural Resources Program of Aztec Ruins National Monument, we politely request that harvesting of plants not occur on the monument unless (and only if) permission is gained in advance. If, somewhere besides the monument, you have permission to collect, we advise you to take precaution in the harvesting and use of wild native plants because of the potential health and safety risk. This is a non-comprehensive tool aimed at introducing and educating the public to wild native plants of the San Juan Basin; furthermore, more specific information regarding the medicinal uses of the plants mentioned in this guide should be gathered from other sources; the list of references used in creating this guide is at the bottom of the page. It is important to recognize that the origins of ethnobotanical knowledge are linked to indigenous communities all around the world; and that for many indigenous cultures there continues to be a shared relationship with the plant communities they have been interacting with for thousands of years. Lack of knowledge surrounding the harvesting of native plant communities has in some cases resulted in overharvesting throughout the country; a good rule of thumb is to learn about best harvesting practices for your area as well as plant communities that are particularly vulnerable or at risk. It is part of the mission of the National Parks “to preserve unimpaired the natural and cultural resources and values of the National Parks System for the enjoyment, education, and inspiration of this and future generations.” Based on the park’s mission, it’s our goal at Aztec Ruins to preserve native wild plant populations within the natural landscape, and to help educate the public about the work of preserving our public lands. As the Natural Resources Program, we hope that in reading this guide you will walk away having learned something new.

ShrubsBroom SnakeweedGutierrezia sarothrae

Characteristics: In the Four Corners region, Broom Snakeweed grows as low growing shrubs, with resinous linear leaves and small flower heads, with yellow ray and disk flowers that appear from May to November. Distribution and Ecology: Broom Snakeweed grows throughout most of western North America at elevations from 3000 to 7000 feet, from Canada through southern California, east to Texas, and south to central Mexico. It can be found on slopes, in the plains, and a wide variety of habitats. Ethnbotanical Uses: For the Pueblo communities living in New Mexico, Broom Snakeweed is an incredibly important plant for medicine and ceremonies, and can be used for a wide variety of applications. They also use the flowers to make a yellow dye.

BuckwheatEriogonum, Polygonum, and Rumex spp.

Characteristics: The buckwheat family is a highly diverse family of plants. Plants in this family have simple, toothless leaves and often swollen joints, known as "nodes," on the leaf stems. Buckwheat plants also commonly produce sour juices consisting of oxalic or tannic acid, both of which can be toxic to humans; therefore, these plants should be harvested and prepared with care. The flowers are usually arranged into complex clusters such as spikes, racemes, and heads, and they range in color from white, pink, red, or yellow. The flowers provide a nectar source for bees, who produce a dark-colored honey when feeding on it, and buckwheat is also sought after as a forage plant by deer and other grazing animals. In the San Juan Basin, there are a handful of species representing this family. The species most commonly found at the Aztec Ruins native plant trail is Antelope-Sage Buckwheat (Eriogonum jamesii, to the left). Other species present in the area (all shown below) include pin cushion buckwheat (Eriogonum ovalifolioum, left), Curly Dock (Rumex crispus, center), and Nodding Buckwheat (Eriogonum cernuum, right). Distribution and Ecology: The buckwheat family is the largest group of plants native to North America, in regards to the total number of species, and about 250 species can be found spread across the temperate (non-tropical and non-polar) portions of North America. Buckwheat plants are highly adaptable to various soil and climate conditions, as well as to low soil fertility and pH, the latter of which produces highly acidic soils that many plants cannot tolerate. Buckwheat plants are often a pioneer species as a result of this, and the residue that they leave behind helps to increase the amount of organic matter and phosphorous in the soil, making it easier for other plants to grow. Ethnobotanical Uses: Members of the buckwheat family have been used by many groups living in the Four Corners region. Plant parts have been found in hearths and preserve in coprolites at ancestral Pueblo sites, demonstrating their long history of human use. The seeds, stalks, leaves, roots, and stems have all been used as food: the seeds in soups or ground into mush, the stalks boiled and pressed into cakes, and the boiled leaves ground and made into bread along with cornmeal. Additonally, buckwheat plants have been used to make yellow and green dyes, and for a seemingly endless variety of medicinal uses.

ChokecherryPrunus virginiana

Characteristics: Chokecherry can grow as either a large, deciduous shrub or a small understory tree, ranging from 20 to 30 feet tall and often forming thickets. Dense clusters of small, elongated flowers appear from April to June and hang downward, turning into dark purple and black fruits later in the season. The twigs and bark can be distinguished by lens-shaped reddish brown markings. Distribution and Ecology: Chokecherry is the most common native cherry species in North America, and can be found in conifer forests and other woodland areas across much of the continent, at elevations ranging from 4500 to 8000 feet. Ethnobotanical Uses: The small, edible fruits of the Chokecherry plant have commonly been harvested by a variety of indigenous peoples living across North America. In the Four Corners region, the hard pits of the fruit have been found preserved in coprolites. The fruits may be eaten fresh, dried to be saved for later or to be ground into a meal, or cooked into desserts, preserves, and sauces. In addition, chokecherry wood has been used to make bows and ceremonial objects, while other parts of the tree have been combined with other plants into a purplish-brown dye.

Coyote WillowSalix exiguaCharacteristics: Of the willow species that can be found in the Four Corners region, Coyote Willow is the most common. It can be distinguished from Gooding's Willow (Salix gooddingii), the other common willow species in riparian areas of the southwest, by its low stature of 6 to 8 feet and its habit of growing in colonial, dense thickets; Gooding's Willow tends to grow as tall trees. Like many of its relatives, Coyote Willow has narrow leaves and clumped flowers. Distribution and Ecology: Coyote Willow can be found throughout western North America, from California east to Texas, north to Canada, and south to northern Mexico. Ethnobotanical Uses: Willow plants contain salicin compounds, which, when ingested, break down into salicylic acid, the main ingredient in aspirin. Before synthesized painkillers were developed, indigenous peoples of North America used willow to make pain medicines, as well as to treat coughs and sore throats. Aside from its prominent medicinal uses, willow wood is verstaile and can be used to make roof thatching, loom parts, bows, snowshoe frames, pot rests, mats, scraps, cradle parts, and baskets. Various parts of Coyote Willow have been used to make green and rose-tan dyes, and the plant has also been important for ritual and ceremony.

JointfirEphedra spp.Characteristics: Jointfir is a sparse-looking shrub, growing up to a yard or so in height, with jointed stems, scale-like leaves, and opposite or whorled branching. In the San Juan Basin, two species are common: Cutler's Jointfir (Ephedra cutleri, left), which is a green-yellow in color, and the Nevada Jointfir (Ephedra cutleri, right), which is blue-green. Jointfir plants are gymnosperms, close relatives of pines and other conifers, and they produce small cones instead of flowers, usually in late winter and spring. Distribution and Ecology: Ephedra species can be found in dry areas of both the Western and Eastern Hemispheres. In the Americas, they can be found in the southwestern United States as well as parts of Mexico and South America. The plants are drought-tolerant and favor dry, flat, sandy areas as well as rocky slopes, normally at lower elevations (in the pinyon-juniper ecozone or below). Ethnobotanical Uses: Jointfir species have a long history of use among the indigenous peoples of the Four Corners region; parts of these plants, for example, have been found in coprolites at ancestral Pueblo sites. The seeds can be roasted and ground into flour, while the plant also is useful for making light tan or reddish dyes and in the process of tanning animal hides. The plant is popularly known as "Mormon Tea," and even today a brewed tea made from the plant has a variety of medicinal uses among the modern Pueblo peoples.

Four-Wing SaltbushAtriplex canescensCharacteristics: Four-wing saltbush is a common shrub in the San Juan Basin, and it is identifiable via its narrow leaves and distinctive four-winged fruits. The leaves are eaten by livestock, deer, and pronghorn antelope, while birds and rodents eat the seeds. The flowers appear in spring and summer, and the fruit in late summer. Distribution and Ecology: This plant can be found throughout most of western north America, from Alberta as far south as southern Mexico, and east to Texas; it has also been introduced to Australia. It can be found in sandy and gravelly soils, from desert scrub to pinyon-juniper communities ranging from 300 to 6500 feet. Four-Wing Saltbush is appropriately named in more than one way, for it is also very tolerant of saline soils. Ethnobotanical Uses: Four-wing saltbush is a common shrub at Aztec Ruins National Monument, and historically and prehistorically it has served many purposes for indigenous groups in the Four Corners region. The seeds were ground and cooked into cereal, while the leaves were one of the earliest available spring greens each season; the leaves could also be made into flour along with other ingredients, being turned into bread and cakes. The ashes of this plant have been used like baking soda to leaven bread, and the distinctive bluish color of Hopi piki bread comes from this plant as well. The wood can be used as fuel, and many parts of the plant have a variety of medicinal and ceremonial uses.

GreasewoodSarcobatus vermiculatus

Characteristics: Greasewood is a native flowering perennial plant, with the flowers appearing from spring to summer and turning into fruits in late summer and fall. The branches are brittle, and taper to sharp thorns, while the deciduous leaves are fleshy and narrow. The seeds have long wings that are barely half an inch long; the wings allow them to be carried by the wind and pollinated by wind dispersal. Distribution and Ecology: Greasewood can be found in saline and alkaline soils in a variety of habitats: semiarid and arid plains, alkali flats, slopes, desert-scrub communities, sagebrush, salt flats, roadsides, fencerows, and dry washes. Ranging from 500 to 8000 feet, it occurs throughout much of western North America, from Alberta and Saskatchewan as far south as northern Mexico, and east to the Dakotas, Nebraska, and west Texas. Ethnobotanical Uses: Greasewood is an important shrub in the Four Corners region, and it has been used by a variety of groups. The fruits are edible, but the plant is more important for its usefulness in constructing lintels, weaving objects, needles, scrapers, arrow points, digging sticks, musical rasps, and bows. Greasewood has been used to make dyes, and it is an important plant for ceremonial and medicinal uses

Mountain MahoganyCercocarpus montanusCharacteristics: Mountain Mahogany is a member of the rose family that grows as a perennial shrub (rarely as a larger tree), with smooth pale-gray to reddish bark; the older bark on the plants will be flecked with scales. The leaves are deciduous, alternate, and simple, while the flowers (which bloom from March to July) are white-to-pinkish and eventually produce a long plume which comprises the plant's fruit. These plumes have a silvery appearance, occasionally making the plants themselves appear silver from a distance if a lot of the plumes are present. Mountain mahogany is an important desert plant for several reasons: for one thing, it is one of the few desert plants that can fix nitrogen to the soil the same way that peas and beans do, and it is also highly fire-tolerant, with new sprouts coming right from the base of the burned shrub after a wildfire. Distribution and Ecology: Mountain mahogany can be found on dry slopes and along washes from 1000 to 7000 feet, often in pinyon-juniper and mixed conifer woodlands. It spreads throughout most of the western US: Texas north to Montana and Idaho, southwest to California, and south to central Mexico. Ethnobotanical Uses: Mountain mahogany has long been an important plant for the peoples of the Four Corners area. The dense wood has been used to make tools, hunting instruments, toys, and construction materials. In addition, the plant produces various shades of red and brown dyes that are used for coloring baskets, moccasins, leggins, and wool. It is also an important ceremonial and medicinal plant, and its wood has been used to construct ceremonial objects.

RabbitbrushChrysothamnus nauseoususCharacteristics: The young twigs and leaves of this plant are covered with a fine white wool, which gives it a greyish-green appearance. Dense clusters of yellow green flowers bloom from July to October, turning the crowns a rich gold color. Rabbitbrush has a deep root system that allows it to tap underground moisture. It is common to see small, white round growths on rabbitbrush plants. These are "galls:" growths caused by insect activity. A species of fruit fly lays its eggs in the side of a rabbitbrush stem, and also injects chemical stimulants in the process. This triggers the plant to produce a cottony growth around the developing larva. Distribution and Ecology: Rabbitbrush grows along sandy watercourses in the juniper-grassland and pinyon-juniper ecozones. It can also be found in open spaces in valleys, plains, and foothills from 2000 to 8000 feet. The plant occurs over much of western North America, from British Columbia east to Saskatchewan, and south to Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and California; it can be found as far south as central Mexico. Ethnobotanical Uses: Rabbitbrush has been used to create yellow and green dyes, and the stems were used to color buckskin shirts, leggings, and other cloth materials. Parts of the plant have also been used to make arrows, windbreaks, and woven mats, or incorporated into the weaving of baskets. Rabbitbrush is not a major food source, but the seeds have been used as a supplement to cornmeal mush on occasion. Rabbitbrush, as well as other local species of Chrysothamnus, has been applied by local indigenous peoples for a wild variety of medicinal uses. The ancestral Puebloans and their descendents commonly use rabbitbrush in ceremony; some groups use a mat made out of the plant to close the entrance to a kiva, or they may place its branches on heating stones for a sweat house. Both the ceremonial and medicinal uses are variable, even amongst the different Pueblo cultures.

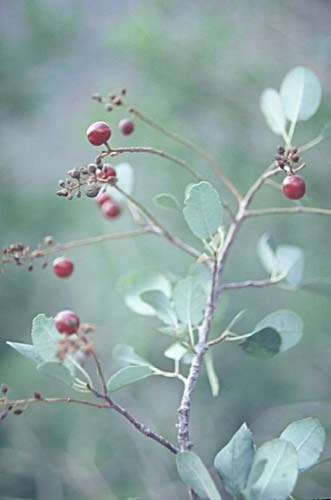

New Mexico PrivetForestiera pubescens var. pubescens

Characteristics: New Mexico Privet is a multi-stemmed, perennial shrub that reaches a mature height of 12 to 15 feet under ideal conditions. It typically grows in dense, almost impenetrable hedges. The leaves are simple, oblong, and light-green in color; new bark is smooth and light gray to brown, while old bark tends to be smooth and gray. The plant has inconspicuous yellow flowers that bloom in dense clusters, producing round-to-oblong drupes (berries) from June to September, with the fruits maturing to a dark bluish-black color. The flowers are an important source of food for pollinators. Distribution and Ecology: This plant grows in a variety of habitats and is a common shrub in southern and western New Mexico. It can also be found in Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, Oklahoma, Texas, and Utah. Ethnobotanical Uses: The most common uses of New Mexico Privet are ceremonial, with the wood being used to make ceremonial objects. The fruits can be made into a dye for the painting of pottery, and the wood can also be used as a digging stick. The leaves are a known emetic, meaning that a person who eats them will vomit.

SagebrushCharacteristics: Sagebrush is part of the genus Artemisia, which also contains aromatic herbs and shrubs such as wormwood and tarragon. The name honors the Greek goddess, Artemis. Contrary to the name, sagebrush is not closely related to culinary sage; sagebrush is in the sunflower family, while culinary sage is in the mint family. Sagebrush and culinary sage do, however, produce similar aromatic compounds, which contributes to the similar smells of their leaves. Most of the different species of sagebrush are evergreen, although a few are deciduous. The growth form ranges from large and expansive to tight little evergreen bundles. One advantage that being evergreen provides to sagebrush is that it can photosynthesize and grow, albeit slowly, during the winter months, when other plants are dormant. Sagebrush also have taproots and wide-spreading root systems that better enable them to take up water and nutrients. The characteristic odor is strongest in the spring, when the plants grow most vigorously, and the leaves are also especially bitter during this time. Distribution and Ecology: Sagebrush dominates much of western North America, with approximately 165 million acres of habitat or potential habitat. Since European settlement began, at least half of that area has been lost to farming, grazing, or development, and the ecosystem is considered to be extremely fragile today. Sage brush steppe provides critically important habitat for endemic wildlife, including sage grouse, sage thrasher, sage sparrow, and pygmy rabbits. Larger wildlife found in sage steppe ecosystems include mule deer, rocky mountain elk, moose, black bears, pronghorn, mountain lions, coyotes, and grey wolves. Ethnobotanical Uses: Sagebrush has a long history of usage by the indigenous peoples of the Four Corners region. Below are three species of sagebrush that can be found on the Native Plant Trail and are common in this region, along with notes on their usage.

Big SagebrushArtemisia tridentataBig sagebrush is one of the most widespread and recognizable species of sagebrush, and it is commonly seen at Aztec Ruins National Monument. Archeologically, the seeds, leaves, and flowers of this plant have been found in coprolites at ancestral Puebloan sites. The wood has been used to create fire by friction, as firewood, or to make brooms, while the leaves and flowers can be manufactured into yellow and gold dyes used to make clothing. This species has a variety of medicinal and ceremonial uses: for example, it is commonly burned as a smudge to clear the air, for ritual purification, and to promote good health.

Sand SageArtemisia filifoliaSand sage is one of the more easily recognizable types of shrubby Artemisia species, as it occurs in sandier soils than other species and often grows alongside yucca and cacti. Sand sage has been mostly used as a medicinal plant, while the softness of its leaves has made it a convenient substitute for toilet paper.

Butterfly picture by Bob Moul, from Butterflies and Moths of North America White SageArtemisia ludoviciana

White Sage has commonly been used in medicine and ceremonies. Throughout the intermountain west, indigenous peoples have used branches of White Sage in sweathouses and other parts of the plant as a medicinal bitter. It has been used to add flavor to meats, or it can be ground into a meal, made into mush, and eaten. It is also, notably, habitat for both the caterpillars and adults of the Painted Lady butterfly.

Threeleaf SumacRhus trilobataCharacteristics: This rounded shrub can grow up to 6 feet high, with the old growth branched and hardened but the new growth being straight and supple. Small yellow flowers, which appear from March to June, grow in clusters along the branchlets, appearing before the leaves emerge. The leaves are in threes, usually lobed and with very closely-toothed margins. Threeleaf Sumac is distinguishable by a solf, velvety pubescence on the stems as well as its pungent leaves, whose odor gives the plant its nickname of "Skunk Bush." The berry-like fruits are orange to red in color, and sticky with short, glandular hairs. Distribution and Ecology: Threeleaf Sumac grows throughout North America, from Alberta south to southern California and even farther south to southern Mexico, and extending as far east as North Dakota. It is found at elevations ranging from 2500 to 7500 feet in dry hillsides, canyons, mesa, and many other biotic communities and habitats. Ethnobotanical Uses: Like many plants of the southwestern United States, indigenous peoples have used this plant for food and medicine in a variety of ways for thousands of years. The berries are delicious but rather acidic, and they can be crushed and sipped as a lovely summer refreshment; one of the plant's other common names, "Lemonade Bush," comes from this use. The berries can also be used as a seasoning, or dried and then ground and made into a jam. Parts of the plant can be made into perfume or insect repellant, as well as black, orange-brown, and blue dyes. The wood of Threeleaf Sumac is an excellent construction material. The new shoots are straight, long, and supple, but when dried they become hard and rigid, and can be used to make bows, arrows, baskets, snowshoes, loom parts, scrapers, awls, hoe handles, and many other items. The wood can also be made into ceremonial objects, and it has been documented as being burned in Kivas for ceremonial fires.

WinterfatKrascheninnikovia lanataCharacteristics: Winterfat is a widespread sub-shrub, conspicuous by its white, greenish-blue color that comes from its densely matted, soft, long, white tangled hairs. The flowers appear from May to October. Distribution and Ecology: This plant occurs in arid regions of western North America at elevations ranging 4500 to 6500 feet. It occurs east of the Cascade Range in Washington and Oregon, south to the Mojave Desert of California, east to the Texas panhandle, and north through the Canadian prairies. It occurs in salt-desert shrub communities alongside fourwing saltbush, greenmolly, shadscale, and black greasewood, and it is a common component of grassland and sagebrush communities as well. Ethnobotanical Uses: Winterfat has been used by several groups within the San Juan Basin for medicine and ceremonies. It is also an important forage plant for livestock.

Wood's RoseRosa woodsiiCharacteristics: Wood's Rose is a deciduous shrub that can grow up to 5 feet in height and often forms dense thickets. The stems are red and prickled on their lower portions, although they are less heavily armed than those of other wild roses. The leaves are pinnately compound, with five to nine leaflets. The plant produces distinct, five-petaled flowers that appear from June to September and transform into orange-red hips in fall. Wood's Rose is an important food source of native bees, as well as for birds, bears, and other mammals, including humans. Distribution and Ecology: This plant's range stretches throughout the western half of the United States and throughout all of lower Canada, being found even as far north as the southernmost portions of the Yukon and Northwest Territories. It can be found along streams and other moist habitats, in ponderosa pine forests, and mountain slopes, ranging from 5500 to 9000 feet in elevation. Ethnobotanical Uses: Wood's Rose has been widely used by the indigenous peoples of this area. Since the stems have a straight growth pattern, they have been used to make shafts for arrows and pipe stems, as well as needles and ceremonial items. The plant has a variety of medicinal uses, and the rose hips, which are a good source of Vitamin C, can be made into tea, jelly, or syrup. Trees

CottonwoodPopulus spp. Cottonwood trees are one of the most common trees found in the riparian (river) ecozone in the southwestern United States. Types of cottonwood that inhabit the San Juan Basin include Fremont (Populus fremontii), Rio Grande (P. deltoides var. wislizeni), and Narrowleaf (P. angustifolia), all of which can hybridize, and none of which are ever found far from rivers and other watercourses. Cottonwoods are closely related to Aspen trees (P. tremuloides), which are not found at Aztec Ruins but do occur in nearby mountain ranges.Characteristics: All three species grow as large deciduous trees, and (appropriately, given the name) are known for having soft, pliable wood. They flower from March to June, with the drooping flowers, known as "catkins," appearing in the spring before the leaves grow out. Narrowleaf Cottonwood is a tree with tan, furrowed bark, and with orange brown twigs that run white by the third year of growth. The leaves are lanceolate, with even serrations. The Fremont Cottonwood is a large tree identified by its coursely-toothed, shiny, and triangular leaves, as well as its large size and spreading crown of branches. The bark is tinged with white, and becomes deeply furrowed as the tree matures. The Rio Grande Cottonwood is a species of the Eastern cottonwood (P. deltoides). Rio Grande Cottonwood trees can be distinguished from the other two species in this area by their ovoid, saucer-shaped fruit capsules, as well as the fact that their branchlets are only sparsely hairy in comparison to the other species. Distribution and Ecology: All of the aforementioned species grow in riparian and other water-rich environments at elevations less than 7500 feet. They occur throughout much of the western United States, from Idaho and Montana as far west as Nevada and Arizona, as far east as Nebraska and Texas, and even as far south as central Mexico. Ethnobotanical Uses: Cottonwood trees have had important uses for nearly every indigenous group in the Four Corners region. The flowers can be eaten raw, the buds can be eaten or used as a sort of chewing gum, and parts of the tree have been used to treat various maladies. Cottonwood, however, is perhaps most important as a construction material. The wood has been used to make roof beams, boats, rafts, scrapers, awls, bows, hearths, cradleboards, snowshoes, and loom frames. In addition, it is considered to be one of the best possible materials for making drums, since the center rots away once the tree dies, making it easy to hollow out.

JuniperJuniperus spp.

Characteristics: Junipers are a type of conifer, closely related to pine trees, cypresses, and redwoods. Most species of Juniperus take the form of large shrubs and small trees, and they can be recognized by their tiny, scale-like, and aromatic leaves, as well as their blue pea-size "berries," which are in fact a special type of cone. They shed pollen between February and April, and like all conifers they do not produce flowers. One-seeded juniper (Juniperus monosperma) and Utah juniper (Juniperus osteosperma) are common in the San Juan Basin; one-seeded juniper can be distinguished by its shreddy bark and the single large seed encased in its berry, befitting its name. Juniper is a slow-growing plant, with the ability to stop active growth when water is limited and to resume growth when wetter conditions arrive. This growth pattern is likely an important adaptation that allows juniper to survive in harsh, arid environments. Distribution and Ecology: Both Utah and one-seeded juniper are common in the desert grassland and pinyon-juniper ecozones throughout New Mexico and southeastern and north-central Arizona. They can also be found in southern Colorado, eastern Utah, western Texas, and western Oklahoma. These two species grow on dry hills, plains, and plateaus, often mixed in with ponderosa pines, pinyon pines, and other juniper species. Ethnobotanical Uses: Both prehistorically, historically, and in the present day (where it is used to make gin), juniper has had a variety of uses. Indigenous peoples of the Four Corners region have used these plants for millenia, and a greater variety of uses may be attributed to this plant than just about any other plant listed in this guide. Juniper berries, which reliably appear just about every year, even during times of drought, were a staple wild food in the diets of the ancestral Pueblo people, and they were especially important during famines. Medicinally, the plant has a wide range of uses, and it is also used ceremonially in dances and sweat baths. The wood, meanwhile, has been used in endless ways: for building and construction, including in Great Houses like Aztec West, as well as to make bows, basket frames, mats, and door coverings. The wood is a reliable source of tinder and firewood, and charcoal from burned juniper has been used to make ceremonial paints. Juniper twigs can also be made into a green dye.

Two-Needle Pinyon PinePinus edulis

Characteristics: Pinyon pines grow as small trees or large shrubs, sometimes up to 50 feet in height but usually shorter. The crowns of the young trees are broadly conical, while those of older trees are flat or spread-out. The plant can be distinguished by having two needles per sheath, with the needles often being sharp and upcurved. The cones are resinous before they open, and they take two years to mature; the mature cones are reddish-orange, with thick and blunt scales, and they lose their seeds at the end of their second growing season. This is the most common pinyon pine species of the Four Corners region, and it is the state tree of New Mexico. Its range overlaps with Pinyon cemborides, which can be distinguished by having three needles per sheath instead. Two-needle pinyon forms a characteristic woodland community with Utah Juniper, with smaller amounts of Mexican Pinyon (P. cembroides) and One-Seeded Juniper being present, and Big Sagebrush, Mountain Mahogany, Rabbit Brush, and other shrubs occuring alongside native grasses in the understory. The wingless seeds of Two-Needle Pinyon are dispersed by birds and small mammals such as squirrels and chipmunks. Scrub jays that live in pinyon-juniper woodlands cache substantial numbers of seeds as winter food, making these birds locally important to the reproduction of the species and the regeneration of these woodlands. It has also been found cached by Clark's nutcracker, pinyon jays, and Steller's jays, frequently outside of the tree's geographic range. Distribution and Ecology: This species can be found as far west as Arizona and Utah, as far east as western Oklahoma and Texas, as far north as Wyoming, and as far south as northern Mexico. It occurs on dry slopes and flats, ranging from 5000 to 7000 feet. Ethnobotanical Uses: Like juniper, Pinyon Pine has a long list of ethnobotanical uses, both in and beyond the San Juan Basin. The trees were used to help construct ancestral Pueblo Great Houses, including those at Aztec Ruins National Monument, and they were also a good source of firewood. Pinyon pitch has been used to waterproof baskets, mend cracked jars, and as a sealant for throwing sticks (which prevents warping). Ceremonially, the needles were burned, and the smoke was inhaled for purifcation. "Pine nuts" from pinyon trees were an important source of wild food for the ancestral Pueblo people, and they are still harvested, traded, and eaten by a variety of peoples in the present day.

Ethnobotany Resource ListNative American Ethnobotany Database. University of Michigan – Dearborn. http://herb.umd.umich.edu/ Visit the database by scanning the QR code to the right.Brandt, Carol B. “Reading the ancestral Puebloan Landscape: a paleoethnobotanist’s text of seeds and wood.” Morrow, Baker. H and Price, V.B. Canyon Gardens: The Ancient Pueblo Landscapes of the American Southwest. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, c2006. Dunmire, W.W. and G.D. Tierney. 1995. Wild Plants of the Pueblo Province: Exploring Ancient and Enduring Uses. Santa Fe, NM: Museum of New Mexico Press. Dunmire, W.W. and G. D. Tierney. 1997. Wild Plants and Native Peoples of the Four Corners. Santa Fe, NM: Museum of New Mexico Press. Heil, K.D., S.L. O’Kane, Jr., L.M. Reeves, and A. Clifford. 2013. Flora of the Four Corners Region: Vascular Plants of the San Juan River Drainage Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah. St. Louis, MO: Missouri Botanical Garden Press. Rainey, Katherine D. and Adams, Karen R. “Plant Use by Native People of the American Southwest: Ethnographic Documentation’. Tull, D. 2013. Edible and useful plants of the southwest. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. General Reference ListBasinger, Ryan. “Food Plot Species Profile: Buckwheat” Quality Deer Management Association. January 14, 2015.“Cylindropuntia Whipplei” The American Southwest – Cacti. https://www.americansouthwest.net/plants/cacti/cylindropuntia-whipplei.html Edmunds, Daly and Nikonow, Hannah. “Celebrating Sagebrush: The Wests Most Important Native Plant.” Audubon. March 2018. https://www.audubon.org/news/celebrating-sagebrush-wests-most-important-native-plant Elpel, Thomas J. “Polygonaceae: Plants of the Buckwheat Family” Wildflowers-and-weeds. Copy right 1998-2019. “Escobaria vivipara.” SW Colorado Wildflowers. https://www.swcoloradowildflowers.com/Pink%20Enlarged%20Photo%20Pages/escobaria%20vivipara.htm “Escobaria vivipara” Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower center. https://www.wildflower.org/plants/result.php?id_plant=esvi2 Gauna, Forest Jay. “Plant of the Week: Prickly Pear” U.S Forest Service. https://www.fs.fed.us/wildflowers/plant-of-the-week/opuntia_basilaris.shtml Gauna, Forest Jay, “Plant of the Week: Sagebrush.” U.S Forest Service. https://www.fs.fed.us/wildflowers/plant-of-the-week/artemisia_tridentata.shtml Gauna, Forest Jay, “Plant of the Week: Spinystar” U.S Forest Service. https://www.fs.fed.us/wildflowers/plant-of-the-week/escobaria_vivipara.shtml Kinsey, Beth. “Escobaria vivipara- Spinystar”. Southeastern Arizona Wildflowers and Plants. Firefly Forest. Copy right 2020. https://www.fireflyforest.com/flowers/1091/escobaria-vivipara-spinystar/ New World Encyclopedia Editors. “Buckwheat” New World Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, Inc. Shultz, Leila. “Pocket Guide to Sagebrush” PRBO Conservation Science. Copy right 2012. http://www.sagegrouseinitiative.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/SGI_Sagebrush_PocketGuide_Nov12.pdf The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica. “Artemisia” Encyclopedia Britannica. Encyclopedia Britannica,inc. April 01, 2010. https://www.britannica.com/plant/artemisia-plant The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica “Ephedra,” Enclycopedia Britannica, Encyclopedia Britannica, inc. May 28, 2019. https://www.britannica.com/plant/Ephedra The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica. “Prickly Pear” Encyclopedia Britannica. Enclycopedia Britannica, inc. August, 2018. https://www.britannica.com/plant/prickly-pear The Editors of Encylopedia Britannica. “Yucca: Encyclopedia Britannica. Encyclopedia Britannica, inc. May 2019. https://www.britannica.com/plant/yucca |

Last updated: September 19, 2022