Canada was seen by many slaves as the promised land: the final terminal on the Underground Railroad, a place to live free from the bonds of servitude. Yet it was not alone as a destination: the Michigan territory also drew runaway slaves to the promise of freedom.

Canada had phased out slavery in 1793, but not all enslaved people had gained immediate freedom. The Michigan Territory held out the prospect of immediate freedom to those brave enough to cross the treacherous Detroit River.

Challenging the Legalities of Slavery

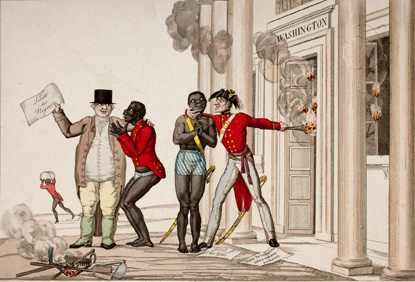

©American Antiquarian Society

Prior to 1807, Detroit, Michigan, slave Peter Denison had been indentured to Elijah Brush for a year, after which Brush granted Denison his freedom. Apparently, Brush had taken this action without the knowledge or approval of his owner, Catherine Tucker. Tucker protested the emancipation and demanded Denison’s return, and a subsequent writ of habeas corpus on behalf of Denison forced the Michigan territorial government to decide on the slavery question. Judge Augustus Woodward ruled in the case that Denison remained Catherine Tucker’s property, that property rights would be upheld, and that all bondsman living in the territory as of May 31, 1793, and belonging to a slaveholder as of July 11, 1796—the day Britain turned the territory over to the United States—would remain a slave. Although the Northwest Ordinance had forbidden slavery in the territory after 1787, the lands the British turned over to the United States in 1796 fell under a different interpretation, and Denison technically remained a slave.

Michigan as a Refuge

This story may be similar to those other early 1800s slaves who tried through the courts to secure their freedom, but Denison’s tale differed. After the 1807 Chesapeake-Leopard affair, territorial governor William Hull offered Denison “a written license,” permitting him to form a militia company of free blacks and runaway slaves. Apparently, Denison had gained the confidence of Detroit’s black population, and according to Hull, under his leadership segregated troops “frequently appeared under arms” and “made considerable progress in military discipline.” Hull maintained that these men demonstrated an unquestioned “attachment to our government, and a determination to aid in the defense of the country.” The crisis that prompted Hull to turn to Denison and the city’s black population soon passed, and the governor disbanded the militia.

Many of Denison’s men had fled from bondage in Canada to the freedom of Michigan; this short-lived southern exodus undermines the traditional image of the Underground Railroad leading north to Canada and freedom. During the late 1700s and early 1800s, the route to freedom most commonly led enslaved peoples south from British Canada to free American territories in the Old Northwest. Canada had phased out slavery in 1793, but not all enslaved people had gained immediate freedom; the institution ended over time, which meant that the Michigan Territory held out the prospect of immediate freedom to those brave enough to cross the treacherous waters of the Detroit River. Yet by the end of the War of 1812, few enslaved people lived in Canada, and Canadian law prohibited the further introduction of slavery. This reality prompted enslaved Americans to venture along a well-trodden path or “underground railroad,” yet thereafter north to a new Canadian land of freedom.

Military Service as a Pathway to Freedom

NPS

During the summer of 1812, Governor Hull issued commissions to Captain Denison, to Lieutenant Ezra Burgess, and to Ensign Bossett—all three black men. Hull insisted that the segregated militia of free blacks and runaways were free citizens of the Michigan Territory, and they, like white citizens, could bear arms in times of crisis. They would shortly be needed as the United States declared war on Britain during June 1812, and Detroit would be the first theater of operations; Denison was apparently captured when Hull surrendered the city to British General Isaac Brock.

By 1816 a black Peter Dennison reportedly lived as a free man in the community of Sandwich and attended the St. John’s Church of England, just east across the river from Detroit. Perhaps this Denison, now listed as Dennison, spelled his name differently or did not correct the church secretary. In either case, he, his wife, and his other children most likely crossed over into Canada, illustrating how within a few short years the path to freedom had shifted dramatically north to the freedom of Canada. Peter Denison undoubtedly seized this opportunity to relocate north to Canada, purportedly as a free man.

Part of a series of articles titled Fighting for Freedom: African Americans and the War of 1812 .

Last updated: March 6, 2015