Because Republicans saw armies, navies and wars as a threat to their party’s principles of limited government, they hoped to fight a different kind of war.

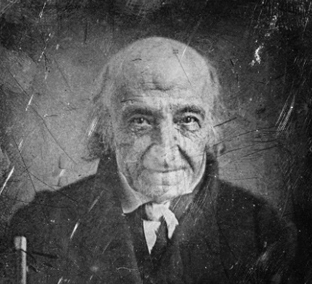

"With respect to the war, it is my wish… that… the United States may be burdened with the smallest possible quantity of debt, perpetual taxation, military establishments, and other corrupting anti-republican habits or institutions." Albert Gallatin

Library of Congress

As it became clear that economic measures against Great Britain were not generating English concessions, the Republican-dominated “War Congress” began preparing for war. At the same time, Congress insisted on keeping both government spending and the military itself small. The contradictions involved in the approach left the nation ill-prepared on the eve of hostilities.

The Republican agenda centered on small government, low taxes, and an ideological loathing of public debt. When the party came to dominate domestic politics, Congress cut military spending and oriented forces to the defensive.

However, wars and the armies that fight them are never cheap, and as talk of conflict intensified, some Republicans pondered whether expanding the government and increasing military expenditures would knock their party from the national stage, giving way to the hated Federalists.

Republicans were also concerned that an enlarged peacetime military establishment might become a tool of oppression. As late as 1810, one congressman actually called for total elimination of the peacetime military, arguing, “unless you use them, the Army and Navy, in times of peace, are engines of oppression…in the hands of an ambitious executive.”

Many senior leaders in the Army were political appointees rather than military professionals. Lieutenant Colonel Winfield Scott bitterly rebuked these “swaggerers, dependents and decayed gentlemen,” and denounced the tendency of partisan congressmen to press “upon the Executive their own particular friends.” The ambivalent political attitude toward standing armies contributed to neglect and sinking morale of the poorly fed and under-paid enlisted ranks.

Republicans sought to curb costs by relying on citizen-soldiers— “the hardy sons of the country” gushed one congressman— rather than more expensive professional soldiers, but relying on militia troops was problematic in a number of ways. Militia were under the control of states rather than federal authorities, making it difficult to coordinate national war aims. Furthermore, legal questions over whether militia could serve abroad raised doubts over their usefulness in a planned invasion of Canada.

Chronically underfunded and understaffed, the War Department— the principal agency directing the war— found itself overwhelmed by the burdens of mobilizing and outfitting for combat along the massive Canadian front.

Mindful that preparing for war threatened to undermine party doctrines, tightfisted and partisan Republicans ultimately shortchanged their nation in what proved to be one of the most disorderly marches to war in American history.

Last updated: May 24, 2016