The idea of waging war against Britain through Canada divided Americans from the start.

“If you had a field to defend in Georgia, it would be very strange to put up a fence in Massachusetts.” Massachusetts Representative Josiah Quincy III

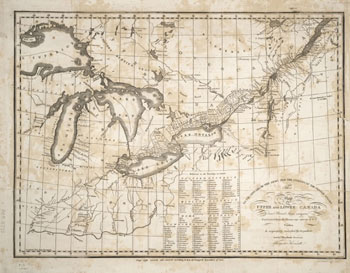

Toronto Public Library

After the British seized four American sailors from the frigate Chesapeake, President Jefferson pressed Congress to pass the Embargo Act in 1807. As it turned out, Jefferson’s experiment with economic warfare did more harm than good, and some disaffected Republicans began to speak of having no alternative but to wage war on Britain.

Thus, as Jefferson stepped down from office in 1809, the incoming Madison administration found itself grappling with the tricky problem of outlining war aims and calculating the means to carry them out. President James Madison and his Republicans wanted to resolve two important issues: ending Britain’s practice of impressment against American sailors, and stopping Britain’s interference with America’s neutral shipping rights.

But the question of means, the strategies by which Madison’s administration would achieve those ends, divided Americans from the start. Given its proximity to the United States, attacking Canada and striking Britain indirectly seemed an attractive strategy. Canada’s apparent vulnerability made it an even more tempting target, since it seemed that it could be conquered with minimal American effort—“a mere matter of marching,” as Thomas Jefferson had put it during his presidency.

But from the perspective of many Federalists, the idea of conducting a massive land campaign against Canada to solve a fundamentally maritime problem seemed absurdly indirect. Massachusetts Representative Josiah Quincy captured this sentiment in a widely publicized congressional speech. "If you had a field to defend in Georgia, it would be very strange to put up a fence in Massachusetts,” Quincy argued. “And yet, how does this differ from invading Canada for the purpose of defending our maritime rights?”

That logic proved persuasive to many Federalists and even some Republicans. Those groups favored a more limited and less costly protection of maritime rights by naval means instead of a land-based invasion. Persistent divisions over America’s strategy would prove a difficult obstacle for much of the war.

Last updated: December 8, 2023