Last updated: June 26, 2019

Article

Storms and Sea Level Rise

NPS photo.

Storms provide the physical conditions that enable some coastal habitats and species to sustain themselves. For example, storm events allow low-lying barrier islands to migrate landwards, helping these ecosystems keep pace with gradually rising seas. Storms are an essential part of the migration process, and are the principal mechanism by which barrier-island systems migrate landward in response to rising sea levels (Leatherman 1988). According to York (2004), “storm waves overwash the islands depositing layers of sand inland of the beach. As the ocean beaches recede, the corresponding buildup of sand across the island toward the sound side allows the islands to retain their elevation above the rising sea level. The newly deposited sand on the sound side provides a base for the islands to migrate onto.”

USGS image.

However, storm surge added to higher sea levels is placing many U.S. coastal areas at increasing risk of erosion and flooding, especially along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts, Pacific islands (e.g., Hawaii), and part of Alaska (Karl et al. 2009). Some scientists think that the most important lesson we can learn from past storms is that as agents of sea-level-rise destruction, storms are almost always the immediate precipitant of disaster (Pilkey and Young 2009). According to Pilkey and Young (2009), “In our modern era of rising sea level, storms will become more important as their impacts push farther into the interior of the beach communities, across barrier islands, and into coastal cities.”

Cape Hatteras National Seashore

Shoreline erosion resulting from sea level rise on both sides of the barrier-island chain is narrowing the width of the long, low islands off the coast of North Carolina. In 2005, the U.S. Geological Survey published an open-file report about the impacts of sea level rise at Cape Hatteras National Seashore (Pendleton et al. 2005). Scientists anticipate that during a storm of sufficient duration and intensity, many new inlets will open up in the barrier, resulting in the isolation of the eight small tourist villages within the national seashore (Pilkey and Young 2009). The owners of threatened homes and businesses in these oceanfront villages at Cape Hatteras have requested beach nourishment to buffer their properties from the ocean’s erosive forces. The National Park Service assisted with the guidance document for this process (Brunner and Beavers 2005).

Everglades National Park

As sea level rises, saltwater will intrude on this vast Florida marsh ecosystem, profoundly changing the flora and fauna. The multibillion-dollar restoration that is under way considers a 1-foot (0.3-m) rise over the next century. However, researchers question what “restoration” will mean in the long term because a 3-foot (0.9-m) rise in sea level is likely for this area (Pilkey and Young 2009).

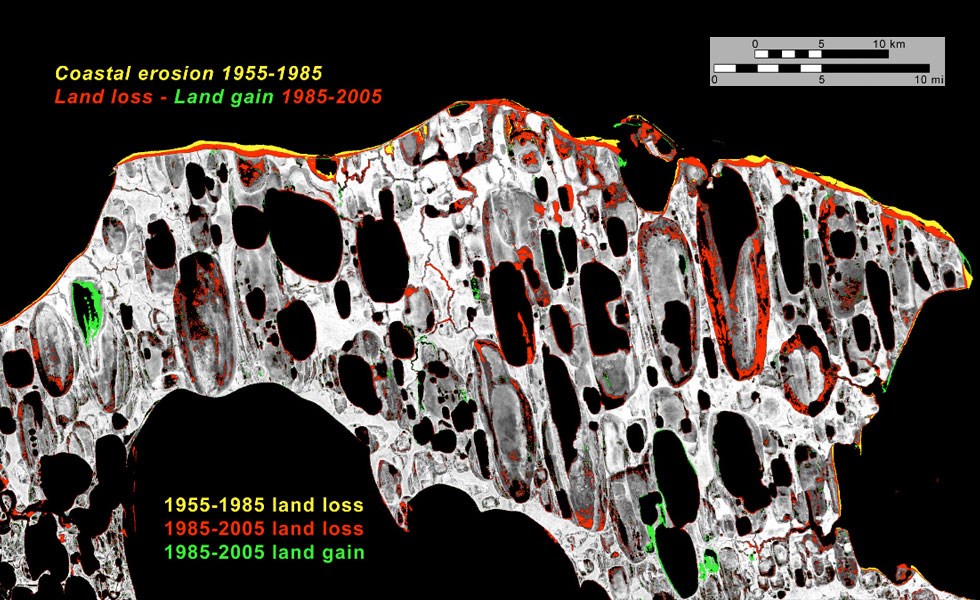

Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve

Perhaps the area most vulnerable to sea level rise in the United States is the Mississippi River Delta, including Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve in Louisiana. The 2005 hurricane season, namely Hurricanes Katrina and Rita, as well as more recent storms such as Hurricanes Gustav and Ike in 2008 have put southern Louisiana on the map, so to speak, with respect to areas that are publicly recognized as being extraordinarily vulnerable to storms. Although these recent hurricanes have enhanced public awareness, this landscape actually has been drowning for decades (Pilkey and Young 2009). A combination of natural and human-induced causes makes the Mississippi River Delta incredibly susceptible to land loss. Over the past 50 years, 40 square miles (100 km2) have been lost annually to subsidence (Pilkey and Young 2009). In the absence of human factors, the delta is naturally subsiding under the weight of sediment deposited by the Mississippi River. However, human-induced changes cause exacerbated amounts of subsidence: water diversion projects (dams and levees) trap sediment that would “build up” the delta, and extraction of groundwater and oil adds to the amount of sinking. Add to this globally rising sea level, and it becomes clear why many scientists consider southern Louisiana as “ground zero” for sea level rise (Pilkey and Young 2009).