Last updated: September 12, 2025

Article

Seals and Homeland: Connected to a Changing World

Learn about the connection between Sugpiat and Alaska Natives of southcentral Alaska and the land through the lens of seal subsistence.

The Meaning of Home

Imagine your home, the place that supports you and helps you thrive. What ways have you observed it change in recent years? Have you found it challenging to adjust to those changes? Maybe you take a new route to get to work because traffic has intensified or maybe you have to frequent a new café because your favorite closed down. Imagine if you relied on your home environment completely for your wellbeing; the land is your teacher, your grocery store, your vessel for memory, and the axis of your community connections. How would you feel the ripple effects if aspects of that environment changed?

For the Sugpiaq People, connection with the land and ocean is paramount. The environment offers people food that they rely on all year round. It nurtures relationships and helps maintain Sugpiaq cultural practices. Although this relationship is so central to Sugpiaq lifeways, it is dynamic. Each element of the ecosystem is interconnected, meaning that a disruption to one element leads to disruptions for many species, humans being one of them.

Photo courtesy of Chugach Regional Resources Commission with permission from Qutekcak Native Tribe

Sugpiaq (Alutiiq) homeland lies across coastal southcentral Alaska, reaching from the Alaska Peninsula to Prince William Sound. Harbor seals are a highly valued subsistence resource in Sugpiaq culture. Community members from the village of Tatitlek in Prince William Sound noted that up to 95 percent of households rely on harbor seals for sustenance (Morton et al.). That being said, community members have noticed declines in seal populations in the last 40 years. In 1999, one community member from Chenega Bay shared a bit about their observations. They said, “[In late ‘70s or early ’80s ] we hunted [all around the area for] 8 days [and caught] 60 seals…This summer when we went up there, there was absolutely nothing… Absolutely nothing. When I say nothing, I mean nothing” (Haynes et al.). Another Elder from the region explained, “The seals, once plentiful, today have become scarce. It was one game animal that provided for the entire community when shared. When the men returned from a hunt, they deposited several seal carcasses on the beach and invited everyone to take home what they needed” (Honoring the Seal). This decline in seal populations influences more than a community’s physical health, but also impacts its cultural and spiritual wellbeing.

Issues Affecting Seals and Our Ocean Ecosystems

There are a multitude of factors that could be contributing to seal population decline. Many of these influences also impact other species within Kenai Fjords National Park in the greater coastal southcentral Alaska region. When several key species are in peril, it often indirectly leads to population decline in other species. One community member from Chenega Bay shared something poignant: “You can’t plant [seals]. If they are on the decline from lack if food, planting them won’t do any good, be a waste of money cause they’ll die from lack of food. What you gonna do? It’s lack of food. Unless you go out and feed them everyday. Ding! Ding! Dinnertime!” (Morton et al.) The problem of reduced food availability is nuanced, and many are working to explore this phenomenon from multiple angles.

Ocean Acidification

USFWS Photo by Roger Tabor

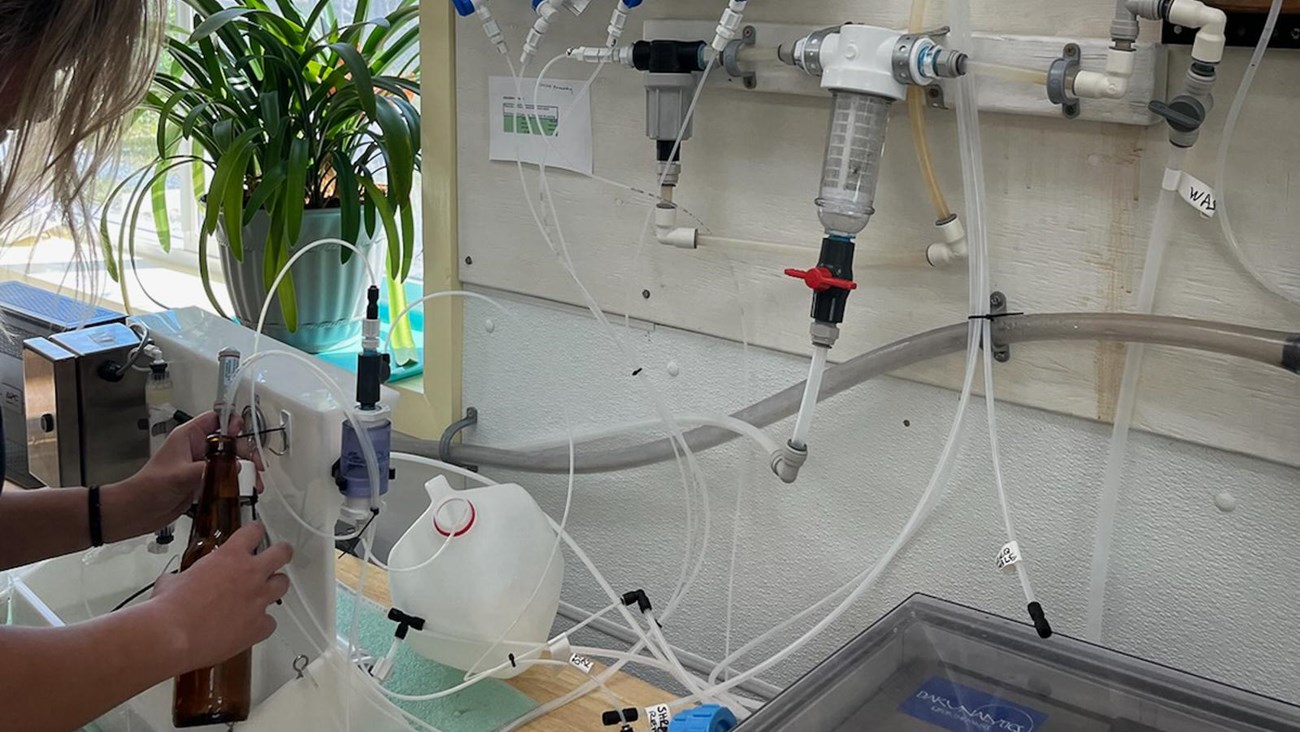

The Alutiiq Pride Marine Institute (APMI), a division of the tribally directed natural resource management organization Chugach Regional Resources Commission (CRRC), is currently researching the impacts of ocean acidification on the abundance of shellfish and marine life in coastal village communities in the region.

As with global warming, the root of ocean acidification lies in excessive carbon emissions. Thirty percent of the carbon dioxide released from burning fossil fuels is absorbed by seawater. As atmospheric carbon dioxide levels rise, the concentration of oceanic carbon dioxide also subsequently increases. This process, known as ocean acidification, changes the chemical properties of sea water. Alaska is particularly susceptible to this process as colder waters absorb more gas than warmer waters. Many organisms depend on the slightly basic oceanic condition that they are adapted to, utilizing a specific mix of ions found in these waters to build their shells and skeletons or to guide their behavioral patterns. Shellfish and fish with larval stages are particularly impacted. With unbalanced ionic conditions, many organisms are unable to reach maturity, leading to noticeable population decline. These species are important food sources for harbor seals and their decline in prevalence may be a reason that seal populations are struggling.

Learn how Sugpiaq communities are affected by shellfish changes, and CRRC is tracking ocean acidification.

Harmful Algal Blooms

Even when food is available, it can still present risks to harbor seal and human communities alike. Kenai Fjords is one of the most supportive environments for plankton blooms. Historically, the abundance of these planktonic algal species has led to an ecosystem overflowing with biodiversity. But it is possible to have too much of a good thing. As climate change warms the waters, algae can bloom at alarming rates, leading to dangerously high levels of biotoxins in some species that would normally be insignificant.

Mammals like seals consume these toxins by ingesting lower trophic level prey that have been exposed. Harmful algal blooms (HABs) pose a true risk to ecosystem health and have been cited as the cause of over 40% of unusual marine mammal mortality events in the contiguous USA over the last 20 years (Lefebvre et al.). One study conducted in Alaska found that harbor seals were the second most affected marine mammal, with many individuals exposed to a toxin that can cause seizures, comas and death in seabirds and marine mammals. While seals and other marine life in Alaska already exhibit detectable levels of algal toxins, they are not yet high enough to be linked to marine mammal mortality. However, they are likely nearing toxic exposure degrees which may already be exacerbating other stressors like ship strikes and dwindling food resources (Lefebvre et al.). The weakening resilience of harbor seal communities impacts subsistence practices in the region and throughout the state.

Photo courtesy of Chugach Regional Resources Commission

Learn how CRRC works with community samplers from tribal communities to detect harmful algae species.

Oil Spills

Natalie Fobes, National Geographic

Uquq kugellrat cimirt'skiat kiaget. Kiaget casaat pekllartuq llumacirpet taumi unguarpet. Cimirt'ski sumacirpet. Takilngurmek pinguq. Cillakcak et'llra imarmi, kiimi, am unguacimt'ni cali. // The oil spill impacted nature's cycles, the seasonal clockwork of our culture, our lifeways. It affected who we are as people. It wasn't just for a short period of time. It had lingering effects, not only in our water but in our lives.

The 1989 Exxon Valdez Oil Spill was a turning point in the history of Kenai Fjords National Park.

NPS Photo

Marine Debris

NPS Photo

Learn how Kenai Fjords and its community partners work to clean "catcher" beaches along the coast.

Learn with Ranger Fiona the efforts to address the impact plastics have on the Kenai Fjords shoreline.

Shrinking Ice

NPS Photo

Human impact to this ecosystem isn’t limited to our addition of marine debris and carbon dioxide, it also encompasses the losses that we have engendered. Tidewater glaciers, which extend from land into the ocean, are a special phenomenon that only exist in several places on Earth. They are characterized by calving events, wherein large ice chunks slough into the ocean, forming ice floes (Bishop). In Alaska, there are only about 50 tidewater glaciers, and 10-15% of harbor seals in the state depend on these ice floes for habitat that is less vulnerable to tidal fluctuations than land-based “haul outs” (Hoover-Miller et al.). Seals use the ice for resting, especially during critical times like their fall molt and pupping seasons.

Kenai Fjords protects several tidewater glaciers that not only provide tidally stable habitats, but also safety from predators and easy access to prey found in estuarine waters. However, due to rapid anthropogenic climate change, glaciers all around the world are receding at unprecedented rates. For example, Northwestern Glacier in Kenai Fjords has receded over 8 kilometers since 1950, nearly retreating out of the water. This retreat means that potentially less ice substrate is available, the implications of which are subject to research at Kenai Fjords.

NPS Photo

Scientists have begun observing harbor seals increasingly hauling out on the rocky shorelines and suspect that this trend may continue or that seals will relocate to other glacial areas. Fewer ice floes and more terrestrial haul out time could have several detrimental impacts to Kenai Fjords harbor seal populations. Researcher Hoover-Miller noticed that with limited ice, pups can be forced to spend long periods of time in the water. This can encourage outsized “energy expenditures and lead to greater incidences of mother-pup separation” (Bishop). Reduced ice habitat can also intensify the spread of diseases due to overcrowding, ultimately leading to higher mortality rates for pups. Additionally, if more seals are forced to haul out on land, that may leave them more vulnerable to predators. In any case, the loss of ice floes disrupts the natural behavior of harbor seals and subjects them to greater risk. Kenai Fjords research on harbor seals is using aerial photography to gain a better understanding of ice habitat from McCarty, Northwestern and Aialik glaciers.

Addressing Our Impact

Seal population decline highlights a critical connection between environmental and human wellbeing. Processes like ocean acidification and climate change are not solely scientific concepts, they directly impact Alaska Native communities through the subsistence practices that have sustained Sugpiaq Ppeople since time immemorial. The urgency of this situation calls for us to come together as scientific researchers, community members, National Parks employees, Alaska Native knowledge holders, and most importantly as humans to address the impacts that we have created. Collective action and work isare needed to sustain the wellbeing of ecosystem, such that future generations may continue to thrive.

Written by Ruby DiCarlo, National Park Service, in collaboration with Robin McKnight and Chugach Regional Resources Commission.

Read On

Learn how the NPS, CRRC and community projects are addressing climate stressors and ocean issues.