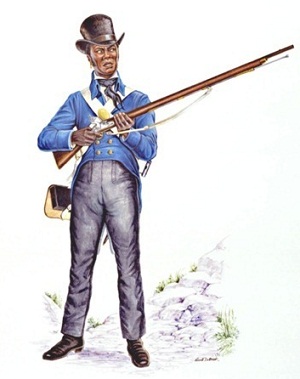

The Coloured Corps, a British unit comprised of black troops, fought with distinction against the Americans, both at Queenston Heights and Fort George. From their perspective, the stakes were high: they fought not just to defend their homes but to preserve their freedom.

“Did our coloured brethren hail [the Americans’] approach? No! On the contrary, they hastened as volunteers … to be foremost to defend the glorious institutions of Great Britain." Sir Francis Bond Head, an officer in the British Army during the War of 1812.

The Harriet Tubman Institute for Research on the Global Migration of African Peoples, Parks Canada.

Early in 1812, a black settler in Upper Canada who had fought against the Americans during the War of Independence proposed that General Issac Brock raise a contingent of black soldiers to fight for the British Army in Canada. Brock initially turned down the offer. But as he became increasingly desperate for volunteers, he reversed course. Brock ultimately formed “Captain Runchey’s Company of Coloured Men.” The company bore the name of its white officer, Robert Runchey, who had a poor reputation throughout the British Army.

Most of the black men who formed the Coloured Corps were Niagara residents. They recognized the dangers they faced if they should fall into American hands. Although many members of the company were free British subjects, some had formerly been enslaved in the American colonies. The men understood that their status as British subjects might not protect them or their families from enslavement if captured. The men of Runchey’s Coloured Corps fought to defend their homes at the risk of their freedom.

Though led by an undistinguished officer, the Coloured Corps fought with distinction at the Battle of Queenston Heights and at Fort George. They were also known for building Fort Mississauga after the British reclaimed the Niagara region. The battlements and central blockade made of brick, taken in part from the remains of burned houses, still stand today.

When the Corps was discharged in 1815, these black Canadian Loyalists began to petition the Crown to receive the land grants promised for their service. That proved a lengthy process; some men died before receiving their grants. Though some descendants eventually received land, it was usually only a fraction of the amount granted to white British soldiers and their families.

Last updated: August 15, 2017