Last updated: March 8, 2019

Article

Dude Ranching at Grand Teton National Park

Ansel Adams (in Series: Ansel Adams Photographs of National Parks and Monuments, 1941-1942, National Archives, 519904)

Grand Teton National Park, established in 1929, is perhaps most well-known by the iconic image captured in 1942 by photographer and environmentalist, Ansel Adams. In the foreground of this photograph, the Wild and Scenic Snake River bends itself through the terraced valley landscape. Central to the image and standing tall at 13,770 feet, the Teton Range spans the background, capped with clouds and light faintly illuminating the jagged terrain.

When this image was captured in 1942, Grand Teton National Park’s boundaries did not include the Snake River. It was not until 1950 that the boundaries were expanded through enabling legislation, and the valley stretching from the Teton Range across the sagebrush flats became part of the natural landscape that remains part of the developmental history of the park.

NPS Photo

Increased visitation to Grand Teton National Park in recent years is testament to the indelible impact that landscapes have on the experience of place.

NPS Photo

It is the natural landscape that drew the first homesteaders and ranchers to the Jackson Hole Valley in the 1800s. Whether those early pioneers were seeking refuge from city living or were drawn by the allure of the "Wild West," men and women from across the nation and world descended on the landscape and have forever left their mark.

Early settlement of Jackson Hole, at least by non-Native American persons, included influential men and women whose long-term presence on the landscape is evident in the few dude ranches and homesteads now located within park boundaries.

White Grass Dude Ranch

NPS Photo

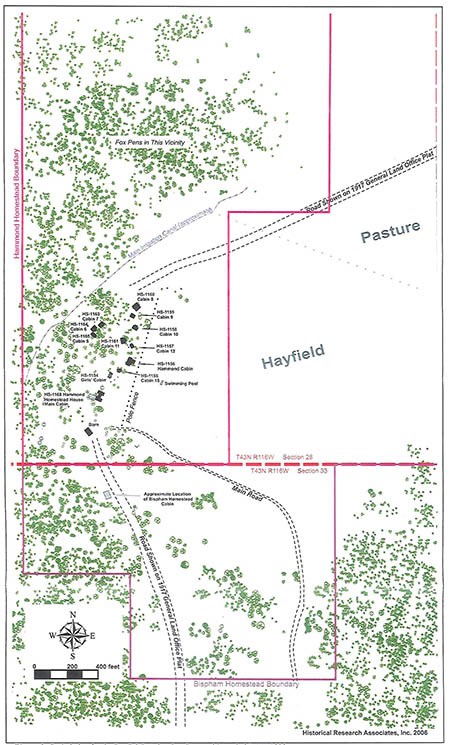

White Grass Ranch is one restored example of this ranching era in Jackson Hole’s long history. Located at the base of Albright Peak and just northeast of Phelps Lake, White Grass Ranch encompassed 320 acres, comprised of two homestead claims made by westerner, Harold Hammond, and a Philadelphian transplant, George Tucker Bispham. Hammond and Bispham made improvements to their adjacent land claims (160-acres per claim) and began receiving paying guests as early as 1919.

In The Diary of a Dude Wrangler, Bar BC founder Maxwell Struthers Burt describes the dude ranch:

Physically it is an ordinary ranch amplified...There is usually a large central ranch-house containing sitting rooms, a dining room, kitchens, storehouses, and so on, and scattered about the grounds, smaller cabins or houses, holding from one to four people, used as sleeping quarters. ... You must do your best, even on a place where from fifty to over a hundred people are gathered together, not to destroy the impression of wilderness and isolation (52).

Produced for NPS White Grass Ranch Cultural Landscape / Historic Structures Report, 2008

Between 1923 and 1928, Hammond and Bispham deeded their claims to Bar BC Ranches, Inc., a partnership that consisted of themselves, Struthers Burt and Horace Carncross (founders of the Bar BC Ranch), and Irving Corse and Sinclair Armstrong. White Grass was designated as the White Grass Ranch for Boys during this partnership. Thirteen cabins were added to the three that were already existing, and a concrete swimming pool was built in the hayfield. During this period, young men traveled to the ranch from from eastern universities in New York. They spent several weeks of the summer learning traditional skills and elements of ranching, emphasizing the spirit of self-reliance.

In 1928, Hammond and Bispham dissolved their partnership with Bar BC Ranches, Inc., and Hammond purchased all real property, buildings, and furnishings from Bispham. Over the next decade and with the help of his first and second wives, Hammond transitioned ranch operations to agricultural use, including cattle, irrigation, and haying. By this time, the ranch infrastructure supported both the dudes and the livestock. A separate bathhouse was constructed, and some dude cabins received bathroom additions.

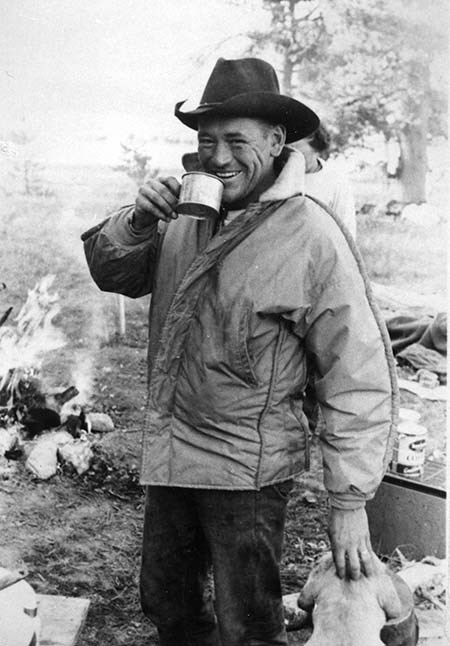

Following Hammond’s death in 1939, his stepson, Frank Galey, assumed management and oversaw day-to-day operation of the ranch. Frank Galey had been born and raised in Philadelphia but had spent many summers in Jackson Hole, visiting Bar BC Ranch as a guest and working for a short time as a White Grass employee. Galey operated White Grass Ranch until his death in 1985, making it the longest-lived active dude ranch in Jackson Hole.

NPS Photo, date unknown

Prior to Galey’s passing, he and his wife, Inge Galey, sold White Grass Ranch to the National Park Service, but they reserved a lifetime estate agreement which allowed the continued use of the property for both residential and guest ranch uses.

Dude Ranch Life

The lifestyle and activities of those who lived and worked on the ranch were intimately connected to the historical patterns of the landscape.

In springtime, horses were kept in the hayfield in front of the cluster of buildings. Ranch hands cleared downed trees along the miles of horse trails, which were simply game trails that had been widened and cleared to accommodate a horse and rider. They mended and reconstructed fences, cut firewood, and sometimes mowed the lawn in front of the Main Cabin.

Each morning, wranglers rounded up horses from the ranch and surrounding land and placed them in the corral next to the barn for use by the dudes. The wranglers turned the horses out to pasture again at the end of each day. Other activities included swimming, fishing, and use of the ranch library and card room.

Staff and dudes ate separately, except on Sunday evenings, when they joined for a barbeque at the pit located on the west edge of the pasture. Staff lived at the ranch during dude season, with the male and female employees housed separately. The cabin for the cook, a springhouse, and the icehouse were gathered in a loose cluster behind the Main Cabin.

Dudes and staff used the water that ran through a main canal behind the main building cluster. Some even excavated small ditches to divert water past their cabins, where they placed bottles and cans to keep their drinks cool. The hops that were planted at the front of some of the buildings for shade and the gravel vehicle roads and informal footpaths that wound around the buildings are still part of the landscape today.

Western Center for Historic Preservation

NPS Photo

Then, in 2005, White Grass Ranch was restored by the National Park Service in partnership with the National Trust for Historic Preservation. By adaptively reusing this cultural landscape, trainees and visitors are introduced to the history of the site as well as to the practical aspects of preservation, stabilization, and rehabilitation.

Today, White Grass Ranch serves as a training facility for the Vanishing Treasures Program, run by the Western Center for Historic Preservation (WCHP). Although some landscape characteristics have been removed, the integrity and historic significance of White Grass Ranch remain and continue to convey this period of Dude Ranching and Tourism in Grand Teton National Park.

Learn More

- Frank Galey Oral History (Wyoming State Archives Oral History Collection)

- HOPE Crew Video Postcard from the White Grass Dude Ranch (National Trust for Historic Preservation)

- Bar BC Ranch National Register Nomination (1990)

- White Grass Ranch Cultural Landscape Inventory park report (2010)

- Bar BC Dude Ranch Cultural Landscape Inventory park report (2011)

- Cultural Landscapes

- Dude Ranches - Grand Teton National Park