Last updated: February 14, 2024

Article

Pipestone National Monument Cultural Landscape

This landscape profile represents the cultural landscape data available as documented by the NPS and interpreted at the park. This article is limited in scope and acknowledges that there are details and perspectives of associated groups that could not be included due to the nature and purpose of the narrative and the potential sensitivity of data.

NPS / N. Barber (2019)

Introduction

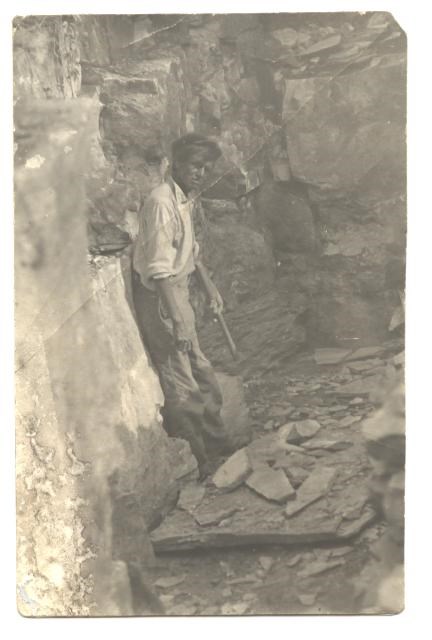

Numerous American Indian tribes consider the Pipestone National Monument landscape sacred.[1] Twenty-three of these tribes have ongoing government-to-government consulting relationships with Pipestone National Monument. Per an 1858 treaty, the Ihanktonwan Nation (Yankton Sioux Tribe) have a particular and special relationship with Pipestone.[2]The quarrying of catlinite, or pipestone, remains an important cultural tradition and is specified in the monument’s founding legislation. After extraction, the pipestone is carved into pipes for ceremonial use and smaller pieces are often carved into other objects. A ceremonial pipe appears in many tribal stories related to religion and ethics, along with other natural features of the landscape, such as the Three Maidens.[3][4] The spiritual guardians of the quarries dwell at these large granite erratics.[5]

A number of ceremonies continue to take place at Pipestone National Monument, including those of prayer and annual Sun Dances.[6] Due to its cultural significance and traditional use over several generations, the National Park Service (NPS) characterizes the landscape as ethnographic.[7]

NPS

Shortly before President Franklin D. Roosevelt created Pipestone National Monument in 1937, the Civilian Conservation Corps – Indian Division (CCC- ID) began initial development and added a footbridge and dam to the site, among other features.[8] The development during the Mission 66 era brought construction of new vehicular and pedestrian circulation systems, parking lots, a residence, and Visitor Center. The Visitor Center embodied the typical Mission 66 design philosophy of simplicity, limited ornamentation, and natural colors.[9] While the Mission 66 features are historically significant today, some also feel these structures compromise the traditional landscape.

NPS

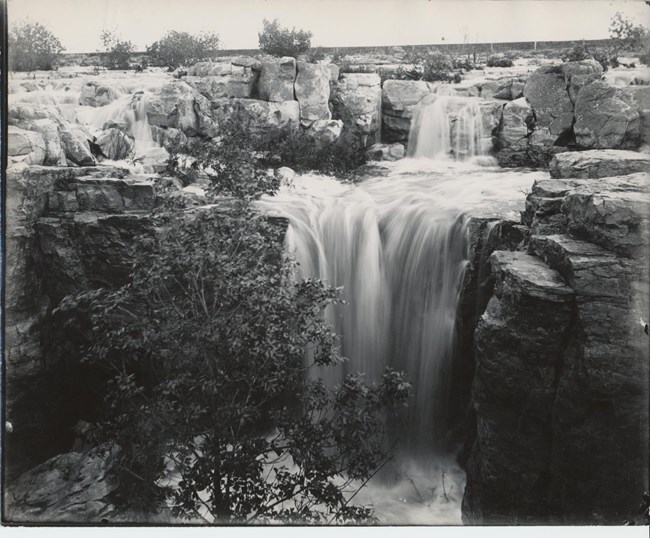

Pipestone National Monument, located in the Couteau des Prairies (the Highland of the Prairie) in Minnesota, contains 301 acres on a glacial plateau.[10] The topography of the glacial plateau varies and includes granite glacial deposits, the largest being the Three Maidens, Sioux quartzite outcrops, and the layers of pipestone itself. The Three Maidens once rested on exposed bedrock containing ancient petroglyphs that frequently featured carvings of turtles and bears.[11] The extant petroglyphs are displayed at the Visitor Center. Distinctive Sioux quartzite landforms includes Leaping Rock/Old Stone Face and the Oracle. Pipestone Creek cascades over a Sioux quartzite escarpment to form the Winnewissa Falls. Several species of freshwater plants reside in riparian zones and wetlands.

The structures related to development under the Mission 66 program include the L-shaped one story Visitor Center, residences, and offices. The CCC-ID development includes two footbridges and the Lake Hiawatha dam. Other historically significant features related to the park development period include some monument roads, pathways, and signage, including the Nicollet historical marker.

Historic Use

Archeological evidence suggests limited pipestone quarrying occurred as early as 2,000 to 3,000 years ago.[12] People traveled great distances to the Great Plains to quarried pipestone for making pipes and other objects. Chief Standing Bear wrote that to the Lakota: “All the meanings of moral duty, ethics, religious and spiritual conceptions were symbolized in the pipe.”[13] Native American tribes perceived the quarry as neutral ground where all could obtain pipestone.

NPS

In 1884, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the earlier Circuit Court decision and upheld the promises contained in the treaty with the Yankton.[17] Initially the decision went unenforced and squatters remained on the reservation. Yankton agent, Major J.F. Kinney, received authorization to remove the squatters with assistance from the U.S. Army. In 1887, Major Kinney and a group of soldiers traveled to the reservation to convince the squatters to vacate.[18] They noticed a railway had been constructed across the reservation and had partially destroyed Winnewissa Falls. The Ihanktonwan (Yankton) decided to sell the right-of-way to the Railway Company and retain all reservation land.

Settlement continued in Pipestone County around the reservation in the late 19th century. During this time, community members proposed the construction of an Indian Boarding School to boost the economy. However, while the Ihanktonwan (Yankton) did not oppose the proposal itself, they objected to its placement on the reservation. Despite Ihanktonwan (Yankton) claim to the land title and right to quarry, Congress passed a law authorizing Pipestone Indian School’s establishment.[19] The school opened in 1893 and operated through 1953. Most of the school buildings were removed or destroyed in the decades after. The Ihanktonwan (Yankton) sought compensation for the unauthorized use of the land for forty years in the legal system. In 1926, the United States Supreme Court ruled that the Ihanktonwan (Yankton) were entitled to compensation for damages, but that the U.S. government retained ownership.[20]

NPS

From 1933 to 1942, the CCC - ID planted trees and constructed a campground shelter, two footbridges, the Lake Hiawatha dam, and other small scale features.[23] In 1952, a Master Plan was developed for Pipestone National Monument under the Mission 66 program. The program provided funds for additional roads, parking lots, trails, residence, exhibits, utilities, and the Visitor Center. After Mission 66 work completed in December 1959, the Parkscape program followed to include the proposal for a cultural and teaching center. In 1972, the center opened as an addition to the Visitor Center with the mission to teach quarrying and pipemaking to a new generation of Native Americans. In addition, the involvement of the Pipestone Indian Shrine Association helped regulate the sale of pipestone crafts. Recently, a decision was made to stop selling pipes at the national monument following many years of dialogue and consultation.

Today, Pipestone National Monument continues to preserve Native Americans’ right to quarry and access the landscape and its resources for ceremonies. In 1991, the first Sun Dance ceremony was held and today two different groups each host each host an annual Sun Dance. The Visitor Center offers interpretive exhibits and demonstrations about the cultural and historic significance of the Monument

Quick Facts

- Cultural Landscape Type: Ethnographic Landscape

- National Register Significance Level: National

- National Register Significance Criteria: A, C, D

- Period of Significance: 1600-1971

Landscape Links

- National Register of Historic Places: Cannomok'e - Pipestone National Monument

- Library of Congress: Pipestone National Monument, HAER Documentation

- Pipestone National Monument, Minnesota Native American Cultural Affiliation and Traditional Association Study (Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology, University of Arizona, 2004)

- More about NPS Cultural Landscapes

[2] Catton , Theodore, and Diane L Krahe. The Blood of the People: NPS Historic Resource Study . NPS, 2016. Pp. 243

[3] Catton , Theodore, and Diane L Krahe. The Blood of the People: NPS Historic Resource Study . NPS, 2016. Pp. 19

[4] Catton , Theodore, and Diane L Krahe. The Blood of the People: NPS Historic Resource Study . NPS, 2016. Pp. 278

[5] Catton , Theodore, and Diane L Krahe. The Blood of the People: NPS Historic Resource Study . NPS, 2016. Pp. 13

[6] Catton , Theodore, and Diane L Krahe. The Blood of the People: NPS Historic Resource Study . NPS, 2016. Pp. 431

[7] CRIS: Pipestone National Monument Cultural Landscape Published Record (501118)

[8] CRIS: Pipestone National Monument Cultural Landscape Published Record (501118)

[9] CRIS: Pipestone National Monument Cultural Landscape Published Record (501118)

[10] CRIS: Pipestone National Monument Cultural Landscape Published Record (501118)

[11] Catton , Theodore, and Diane L Krahe. The Blood of the People: NPS Historic Resource Study . NPS, 2016. Pp. 121

[12] Catton , Theodore, and Diane L Krahe. The Blood of the People: NPS Historic Resource Study . NPS, 2016. Pp. 110

[13] “Land of the Spotted Eagle.” Land of the Spotted Eagle, by Luther Standing Bear, University of Nebraska Press, 2006, pp. 201

[14] CRIS: Pipestone National Monument Cultural Landscape Published Record (501118)

[15] Catton , Theodore, and Diane L Krahe. The Blood of the People: NPS Historic Resource Study . NPS, 2016. Pp. 1

[16] Catton , Theodore, and Diane L Krahe. The Blood of the People: NPS Historic Resource Study . NPS, 2016. Pp. 276

[17] Catton , Theodore, and Diane L Krahe. The Blood of the People: NPS Historic Resource Study . NPS, 2016. Pp. 281

[18] Catton , Theodore, and Diane L Krahe. The Blood of the People: NPS Historic Resource Study . NPS, 2016. Pp. 281

[19]Catton , Theodore, and Diane L Krahe. The Blood of the People: NPS Historic Resource Study . NPS, 2016. Pp. 326

[20] Catton , Theodore, and Diane L Krahe. The Blood of the People: NPS Historic Resource Study . NPS, 2016. Pp.332

[21] Catton , Theodore, and Diane L Krahe. The Blood of the People: NPS Historic Resource Study . NPS, 2016. Pp. 333

[22] Catton , Theodore, and Diane L Krahe. The Blood of the People: NPS Historic Resource Study . NPS, 2016. Pp. 342

[23] Catton , Theodore, and Diane L Krahe. The Blood of the People: NPS Historic Resource Study . NPS, 2016. Pp. 342