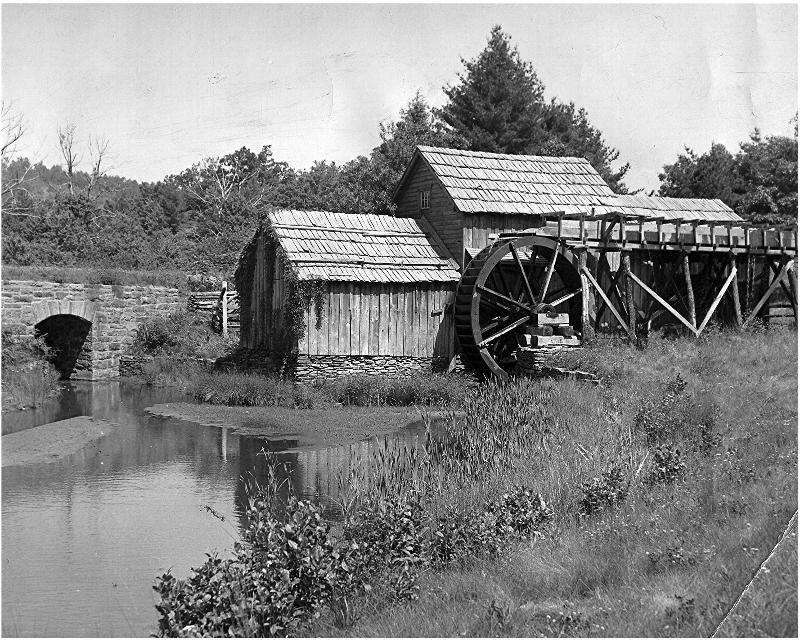

The Blue Ridge Mountains hold numerous traces of settlers and early mountain industries, revealing a way of life closely tied to the land.

Article

Parkway Land Use Maps: Visualizing the Character of the Blue Ridge Parkway

NPS/Abbie Rowe, Harpers Ferry Center Historic Photograph Collection (HPC-000259)

Considering the length of the route, the Blue Ridge Parkway designers realized the importance of providing scenic variety and a diverse driving experience. The road highlights a range of landscapes, rising to capture the most spectacular views in the mountainous sections, and dipping and peeking into gently rolling farmland, high meadows, and low stream valleys.

These principles included:

|

More than just a thoroughfare, the design was intended to expose the interest of this section of the American countryside and offer a comprehensive approach to the conservation of rural landscapes along the route.

Mabry Mill

NPS/Allan Rinehart, Harpers Ferry Center Historic Photos Collection (HPC-000262)

Expressing his thoughts on the value of retaining cutural resources within the road's viewshed, Stanley Abbott said, "...the charm and delight of the Blue Ridge Parkway lies in its ever changing location, in variety. And of course there is the picture it reveals of the Southern Highlands, with miles of split rail fence, with Brinegar cabins and the Mabry Mills. These are evidences of a simple homestead culture and a people whose way of life grew out of the land around them.”1

While the reality of the area was not as simple as once thought, his words capture the perception of those from other part of America who first envisioned the Parkway through the Blue Ridge Mountains.

In 1898, Ed and Lizzie Mabry acquired a 90-acre farm in Virginia. Ed built his blacksmith shop soon after, and the Mabry Mill was built in three stages between 1903 and 1914. During that period, the blacksmith’s shop was moved closer to the mill. With the help of his saw mill and woodworking shop, Ed Mabry built a new frame house for the family around 1914. Their complex expanded to include two barns, a springhouse, a woodshed and washhouse, and a few chicken houses.

Changing technologies allowed larger operations to offer more products in less time for a lower price, leading to a gradual decline of smaller mills. With Ed Mabry's health also in decline, he could no longer maintain the machinery of the mill and it fell into disrepair. When he died in 1936, Lizzie continued to operate the mill with the help of her neighbors. In 1937, she moved into her sister's house, five miles away. The Commonwealth of Virginia gained control of the property in the following year and conveyed it to the Blue Ridge Parkway.2

NPS, Blue Ridge Parkway

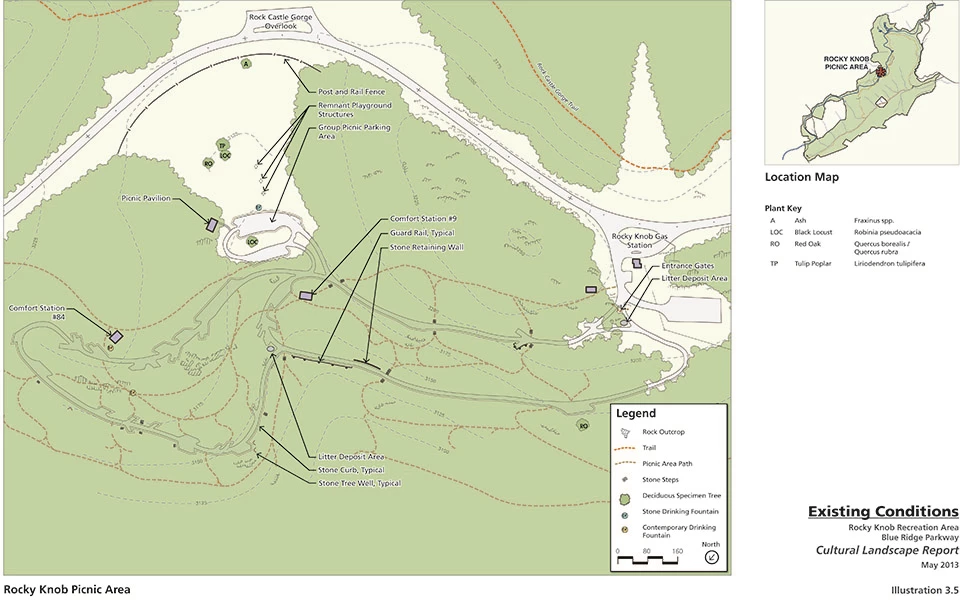

These modifications reflect the ways in which the cultural history of the area was interpreted and incorporated into the Parkway’s development during the landscape’s period of historic significance (1933-1987). Today, the landscape contains a collection of structures and features that illustrate the rural landscape character. The Mabry Mill continues to be a popular stop for Parkway travelers, with historic structures, cultural demonstrations, concerts, and a restaurant.

Mapping the Parkway

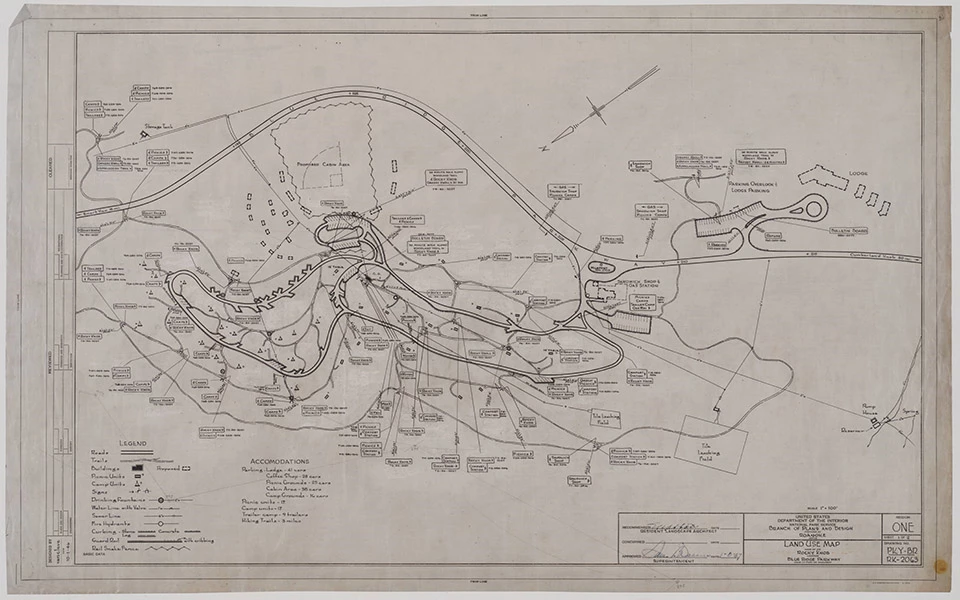

The maps included management information such as adjacent land ownership, public and private roads, utilities, and scenic easements - an indication of the importance of land use on its design.

A series of maps produced during the construction period, referred to as Parkway Land Use Maps or PLUMs, capture the implementation of the design concepts presented by Abbott and Austin. The maps were the result of a study by the National Park Service to “determine the most fruitful use of all lands within the park boundary.”3 They offer extremely detailed documentation of roadside plantings and structures, road alignment, recreation areas, and trails. The maps also include management information such as adjacent land ownership, public and private roads, utilities, and scenic easements - an indication of the importance of land use on its design.

The PLUMs study led to a land leasing program, which allowed for continued maintenance of the landscape’s open agricultural character as cropland or pasture. Since the maps are ‘as-built’ records, they serve as a record of the condition of the Blue Ridge Parkway after construction and continue to be useful reference tools for Parkway staff.4Rocky Knob

Left image

Parkway Land Use Map, Rocky Knob, October 1, 1946

Right image

Existing Conditions at Rocky Knob Picnic Area, in 2013 Cultural Landscape Report

2. Firth, Historic Resource Study, 26.

3. Harley Jolley, Painting with a Comet’s Tail: The Touch of the Landscape Architect on the Blue Ridge Parkway, (Boone: Appalachian Consortium Press, 1987), 13. From NPS Cultural Landscape Report: Rocky Knob Recreation Area – Blue Ridge Parkway, 22.

4. Final Blue Ridge Parkway General Management Plan/Environmental Impact Statement, (U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, January 2013), 7. Accessed at https://parkplanning.nps.gov/document.cfm?parkID=355&projectID=10419&documentID=51305.

Last updated: June 5, 2020