Last updated: October 26, 2021

Article

Night Skies over Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve

As winter draws to a close, it is time to bid farewell to the dark of night in Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve. Summer brings long days that melt the frost set in from winter and begins a frenzied burst of activity for animals and plants alike. These longs days marked the beginning of a busy season of gathering and preserving foods for the indigenous Han Athabascans along the drainages throughout interior Alaska, and they enabled workers to toil beneath the midnight sun during the early 1900s in search of flakes and nuggets of gold in the Coal Creek Historic Mining District.

NPS Photo

Autumn produces the darkest night skies of the year, before the land is covered by a blanket of snow that will reflect any available light source: the moon, cabin lights, or a mushers headlamp. Darkness takes over in winter. At the winter solstice, the sun is above the horizon for just over two hours. In the preserve, the long nights combine with the commonly clear skies of a continental climate to reveal a unique, circumpolar perspective of the night skies.

A Place of Stars and Solar Activity

NPS Photo

In Northern Athabascan cultures, stellar astronomy was an important body of knowledge that enabled people to navigate the landscape during the long winter nights, aided by the concept of a single, large human-like constellation that covered the entire night sky. The human-like figure is present throughout the darkness as it makes its round through the night. Component constellations make up the body parts of the figure. For instance, what western stargazers call the big dipper is generally considered by the Han Athabascans to be the the tail of a much larger figure, referred to as yihjah (Cannon and Holton 2014).

There are variations in the interpretation among different Northern Athabascan cultural groups, but the single, large-sky constellation appears to be a common thread. This knowledge was only recently documented, and supplants previous western views that Northern Athabascan cultures had little in the way of astronomical knowledge. The conception of a whole-sky constellation would have been important for navigation, time reckoning, weather forecasting, and cosmology that is specifically tied to lifeways embedded in a circumpolar landscape (Cannon and Holton 2014).

NPS Image

Aurora is ignited by the interaction of solar winds with the Earth’s magnetosphere, resulting in excitation of gases in the ionosphere that release light at heights of 60 to 300 miles above the earth’s surface (Akasofu 2002). The color of the aurora is most commonly green, but it varies with the level of solar activity and type of gases that alight in the ionosphere and can also be white, purple, pink, and red.

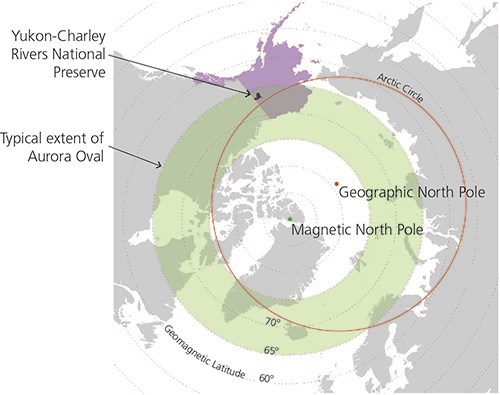

Aurora displays occur in the aurora oval, a region centered around the earth’s magnetic north pole (about 80 miles south of the geographic north pole, in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago), and stretches equatorward on the night time side of the earth. The position of the aurora oval most often lies above about 65 degrees geomagnetic latitude, which overlaps with the Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve. However, the lower boundary of the oval can dynamically expand to lower latitudes when solar storm activity increases, resulting in powerful auroral displays visible at lower latitudes. Historical records document these rare, but strong, auroral events throughout antiquity, often described as a red glowing sky originating in the north (Basurah 2004).

The strongest aurora on record is the Carrington event in 1859, when aurora was recorded in middle to tropical latitudes and disrupted nascent telegraphic infrastructure in the US and Europe (Green and Boardsen 2006). Scientists suggest an event of a similar size could have a large impact on contemporary communications, satellite, and electrical infrastructure.

The strongest aurora on record is the Carrington event in 1859, when aurora was recorded in middle to tropical latitudes and disrupted nascent telegraphic infrastructure in the US and Europe (Green and Boardsen 2006). Scientists suggest an event of a similar size could have a large impact on contemporary communications, satellite, and electrical infrastructure.

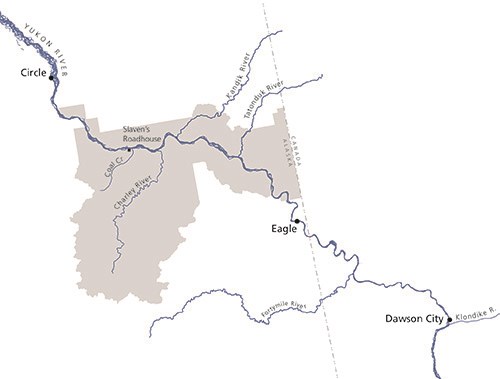

Slaven's Roadhouse

Cultural landscapes in the northern Alaska Region afford majestic views of the aurora borealis, including at Slaven’s Roadhouse, on the banks of the Yukon River. Slaven’s Roadhouse was built in 1932 near the confluence of Coal Creek with the Yukon River, and is a component of the Coal Creek Historic Mining District cultural landscape.

NPS Image

Among the miners in the area was Frank Slaven. He filed his first gold claim in Coal Creek in 1905, and he would work the creek throughout the early mining period before building Slaven’s Roadhouse. The roadhouse served as an important node along the river as mining operations progressed to a much larger scale.

Industrial-scale mining operations were introduced to Coal Creek in the 1930s when Gold Placers, Inc. constructed a four-story dredge that could overturn as much gravel as 2,400 miners working with a pickaxe and shovel could in a single day. Since winter conditions did not permit the extensive process of thawing the earth for dredging, mining activity was concentrated in warmer seasons; dark night skies would have been visible only in the spring and fall. During this era, Slaven’s Roadhouse provided an important stopping point for travelers along the Yukon River, especially in winter when a respite from bitterly cold weather would be more than welcome. Gold Placers, Inc. used the roadhouse area as a landing for mining equipment and supplies, and the roadhouse also served as the local mail stop.

Aurora activity is related to the solar cycle, a measure of the sunspots that can result in strong, active aurora that peaks about every 11 years. Historical records of the solar cycle can provide a proxy of the aurora activity that may have been seen from the Coal Creek Historic Mining District.

The graph shows that contemporary levels of aurora activity are similar to what may have been visible when gold rushes struck the region and during the early mining period. Winter visitors to Slaven’s Roadhouse may have enjoyed particularly lively northern lights during the years that Gold Placer’s, Inc was dredging the creek.

The graph shows that contemporary levels of aurora activity are similar to what may have been visible when gold rushes struck the region and during the early mining period. Winter visitors to Slaven’s Roadhouse may have enjoyed particularly lively northern lights during the years that Gold Placer’s, Inc was dredging the creek.

Today Slaven’s Roadhouse serves as one of seven public use cabins available in the preserve, accessible by boat, plane or sled. Slaven’s Roadhouse is also a rest stop along the Yukon Quest, a 1,000-mile international sled dog race between Fairbanks, Alaska and Whitehorse, Yukon Territory. The race enlivens the traditional mode of winter transportation that was used to navigate the landscape long before miners arrived, during a time when a rich knowledge of the stars would have been important.

A timelapse of the night sky above Slaven’s Roadhouse during the 2016 Yukon Quest shows a fantastic aurora display, the glow of the lights from the historic cabin, and the journey of yihjah as it walks across the night.

A timelapse of the night sky above Slaven’s Roadhouse during the 2016 Yukon Quest shows a fantastic aurora display, the glow of the lights from the historic cabin, and the journey of yihjah as it walks across the night.

The requested video is no longer available.

References

Akasofu, S., Finch, Jack, & Curtis, Jan. (2002). Secrets of the aurora borealis. Alaska Geographic, 29(1). Anchorage: Alaska Geographic Society.

Basurah, H. (2004). Auroral evidence for early high solar activities. Solar Physics, 225(1), 209-212.

Beckstead, D. (2003). The World Turned Upside Down: A History of Mining on Coal Creek and Woodchopper Creek. Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve, Alaska: US Department of the Interior, National Park Service.

Cannon, C. and Holton, G. (2014). A newly documented whole-sky circumpolar constellation in Alaskan Gwich’in. Arctic Anthropology, 51(2), 1-8.

Green, & Boardsen. (2006). Duration and extent of the great auroral storm of 1859. Advances in Space Research, 38(2), 130-135.

Mishler, C., & Simeone, William E. (2004). Han, people of the river : Hän hwëch'in : An ethnography and ethnohistory. Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press.

SILSO, World Data Center (2018). Sunspot Number and Long-term Solar Observations, Royal Observatory of Belgium, on-line Sunspot Number catalogue: http://www.sidc.be/SILSO/, accessed April 30, 2018.