Last updated: August 15, 2021

Article

NETN Field Note: Deer, Worms, and Invasives

NPS photo.

Forest Health Monitoring Insights from the 2018 Season

No - the title of this article isn’t a misdirected parody of a well-known Warren Zevon classic, it is what forest ecologists are seeing more of in the woodlands of the northeast, however. As part of a long-term monitoring program, five NETN parks were visited by our forest health crew this spring and summer: Acadia National Park (ME), Marsh-Billings-Rockefeller National Historical Park (VT), Minute Man National Historical Park (MA), Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site (NH), andSaratoga National Historical Park (NY). These parks are different in many ways, but there are some themes that connect them, and many other NETN parks, on the forest floor. The following are some trends documented by recent monitoring efforts.

Ed Sharron

Forests becoming more complex as they age

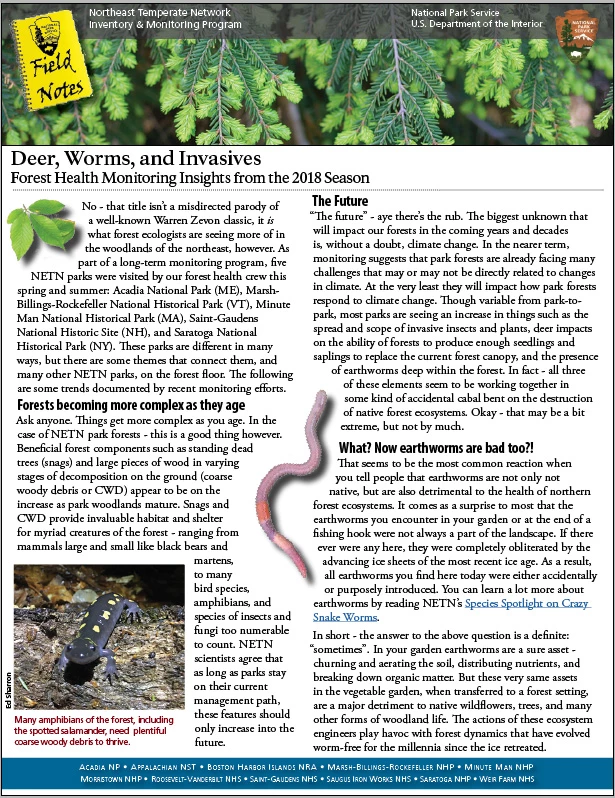

Ask anyone. Things get more complex as you age. In the case of NETN park forests - this is a good thing however. Beneficial forest components such as standing dead trees (snags) and large pieces of wood in varying stages of decomposition on the ground (coarse woody debris or CWD) appear to be on the increase as park woodlands mature. Snags and CWD provide invaluable habitat and shelter for myriad creatures of the forest - ranging from mammals large and small like black bears and martens, to many bird species, amphibians, and species of insects and fungi too numerable to count. NETN scientists agree that as long as parks stay on their current management path, these features should only increase into the future.

The Future

“The future” - aye there’s the rub. The biggest unknown that will impact our forests in the coming years and decades is, without a doubt, climate change. In the nearer term, monitoring suggests that park forests are already facing many challenges that may or may not be directly related to changes in climate. At the very least they will impact how park forests respond to climate change. Though variable from park-to-park, most parks are seeing an increase in things such as the spread and scope of invasive insects and plants, deer impacts on the ability of forests to produce enough seedlings and saplings to replace the current forest canopy, and the presence of earthworms deep within the forest. In fact - all three of these elements seem to be working together in some kind of accidental cabal bent on the destruction of native forest ecosystems. Okay - that may be a bit extreme, but not by much.

What? Now earthworms are bad too?!

That seems to be the most common reaction when you tell people that earthworms are not only not native, but are also detrimental to the health of northern forest ecosystems. It comes as a surprise to most that the earthworms you encounter in your garden or at the end of a fishing hook were not always a part of the landscape. If there ever were any here, they were completely obliterated by the advancing ice sheets of the most recent ice age. As a result, all earthworms you find here today were either accidentally or purposely introduced. You can learn a lot more about earthworms by reading NETN’s Species Spotlight on Crazy Snake Worms.

In short - the answer to the above question is a definite: “sometimes”. In your garden earthworms are a sure asset - churning and aerating the soil, distributing nutrients, and breaking down organic matter. But these very same assets in the vegetable garden, when transferred to a forest setting, are a major detriment to native wildflowers, trees, and many other forms of woodland life. The actions of these ecosystem engineers play havoc with forest dynamics that have evolved worm-free for the millennia since the ice retreated.

NPS photo.

You are probably starting to see how these invasives scratch each other’s backs: buckthorn and barberry optimize the forest environment for earthworms by providing high-quality leaf litter and shade, and earthworms help perpetuate buckthorn/barberry germination by gorging on leaf litter, pumping the system with nitrates, and exposing bare soil. The higher levels of calcium in buckthorn leaf litter also benefits earthworms, which need it for proper bodily functions. As one might expect, more than one study has shown earthworm density is greater closer to invasive barberry/buckthorn thickets.

Now on to the third spoke in our wheel of misfortune for northeastern forests: ever-increasing numbers of deer.

Doh! A Deer. A Heckuva Lot of Deer.

Deer love living on the edge, and people love giving an edge - not purposefully, necessarily, to deer. The places where the farm meets the forest, or where people’s yards abut a woodland, are referred to in ecologist parlance as “edge habitat”, and the countryside of the eastern and northeastern US is downright lousy with this kind of ecological zone. The lack of “top line” predators and the continual creation of edge zones has provided ideal conditions for the deer population to explode.All these deer eat a lot of vegetation - about 7 lbs per day (over 1 ton per year) for the average deer. Just like anything else that eats - they have their preferred list of menu items. Most of their favorite foods, logically, are native plant species that they have evolved with over the millennia. This leads to higher “deer herbivory” pressures on native plants, and helps many non-native invasive species flourish in high deer density areas. As deer apply more pressure to native species, they free up space and other resources that invasive species are poised to take advantage of.

This stress can also actually change the physiology (internal function) of plants in some cases. One study made use of deer exclosures to examine the proliferation of invasive Japanese stiltgrass. In places without fences and plentiful deer, unsurprisingly, there was a strong negative effect on the amount native plant species. More interesting, summer deer feeding led to smaller leaves on many plants, including some invasives. The Japanese stiltgrass and garlic mustard actually upped their photosynthesis process, and natives like Trillium showed a drop in their maximum photosynthetic rates.

Friends of the Mississippi River photo.

Deer Get By with a Little ELP From the Fiends

Extended leaf phenology, AKA ELP, is a trait many invasive plants share. In essence, it means they have earlier leaf emergence and/or later leaf drop than most native plants, and it’s considered to be one of the advantages that helps them thrive in many areas. For example, amur honeysuckle leaves start developing 2–3 weeks earlier than that of the many natives growing in the same habitats in parts of the east. Several nonnative woody species, like Japanese honeysuckle, and our friends buckthorn and barberry, extend their autumn growing season by about an extra month longer than compared with natives. This prolonged access to light and nutrients leads to increased growth.The ELP of invasive plant species may also lead to increased deer populations, cranking-up pressures on native plant species. A study that looked into this theory examined the proportion of a deer’s diet comprised of amur honeysuckle. Researchers found that deer browsed honeysuckle during all growing months, but consumption was highest in early spring and late summer. Thus the honeysuckle, perhaps along with other ELP’s, provided enough food in the shoulder seasons to raise the deer population so that native species are hit harder during the non ELP periods.

Along with earthworms, deer and invasive plants are contributing to the increased lack of regeneration of native trees and understory plants, and to what some forest ecologists call “forest decline syndrome”. How to slow or prevent this trend from continuting into the future is a complicated task. However some success has been achieved in parks and other natural areas that have applied deer control methods and that have active invasive species pulling programs.

For More Information.

Stop by NETN’s webpage about the forest health monitoring program. There you will find links to monitoring reports and briefs, journal articles, and in-depth details about how monitoring is accomplished in park forests.Download a printable PDF of this article.

Tags

- acadia national park

- appalachian national scenic trail

- boston harbor islands national recreation area

- eleanor roosevelt national historic site

- home of franklin d roosevelt national historic site

- marsh - billings - rockefeller national historical park

- minute man national historical park

- morristown national historical park

- saint-gaudens national historical park

- salem maritime national historical park

- saratoga national historical park

- saugus iron works national historic site

- vanderbilt mansion national historic site

- weir farm national historical park

- species spotlight

- netn

- climate change

- global warming

- global warming/climate change

- forest health

- deer

- deer browse

- white tail deer

- earthworms

- invasive species