Last updated: August 25, 2022

Article

More Impact for More People: Geoscientists-in-the-Parks internship program advances park science, promotes stewardship, and launches careers

Andrea Spahn

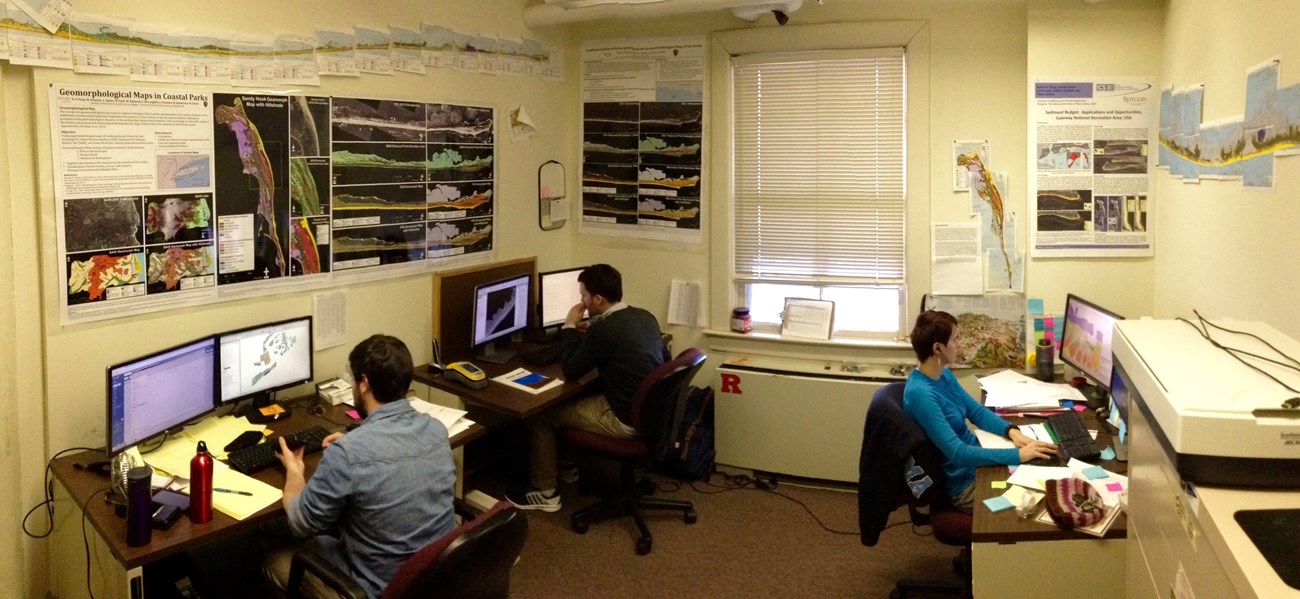

As Geoscientists-in-the-Parks (GIP) interns, John Schmelz and Katy Ames conducted post-Hurricane Sandy park science and monitoring research.

John Schmelz began his GIP internship with a student’s readiness to learn. But by summer’s end, he was thinking like a professional. His focus shifted from the particulars of methodology and technical minutia to the urgent needs that drive scientific research and the practical applications that can emerge from it.

With funding from the National Park Service (NPS), Schmelz’s GIP internship took him to the Sandy Hook unit of Gateway National Recreation Area (NRA) in New Jersey, where Dr. Norb Psuty of Rutgers University and his team in the Sandy Hook Cooperative Research Programs conduct monitoring research and post-storm mitigation and resilience studies for the NPS Northeast Coastal and Barrier Network's Inventory and Monitoring Program.

The National Park Service and the Geological Society of America (GSA) partner together to deliver unmatched experiential learning opportunities through the Geoscientists-in-the-Parks (GIP) Program (formerly GeoCorps) since 1997. Through this program, NPS and GSA provide aspiring natural resource scientists and geoscientists with paid short-term internships in public lands, including National Park sites across the country, where the interns contribute to all forms of natural resource monitoring, research, and science communication. Starting in 2016, the NPS partners with Stewards Individual Placement Program (Stewards) to administer the GIP Program.

Andrea Habeck

Schmelz began his 12-week summer internship in May of 2012, two years after he graduated from Connecticut College with an environmental studies degree, and months before Hurricane Sandy struck. He had studied biology, ecology, hydrology, and geology, and he had a strong affinity for the study of coastal dynamics, but the GIP program gave Schmelz something that coursework alone did not: unparalleled site-based, hands-on experiences.

He contributed to research at almost every stage of its development, from collecting data with state-of-the-art equipment to performing spatial analyses and collaborating on professional scientific reports and papers. Eventually, Schmelz accepted a job offer from Psuty, his internship supervisor. While Schmelz’s experience is remarkable, it is not entirely unique. GIP internships are designed to be a bridge to advanced degrees, publication, and careers in the sciences.

Schmelz describes Psuty as a teacher and mentor, and his time working for Psuty was formative. “He’s very good at explaining things to you in a way that, really, anyone can understand,” Schmelz says, adding that Psuty’s patience, willingness to teach, and welcoming attitude helped him to learn and grow by leaps and bounds.

Josh Greenberg (Rutgers Staff), Andrea Spahn (Rutgers Staff), Katy Ames (GIP Intern), John Schmelz (Rutgers Staff, former GIP Intern), Irina Beal (Rutgers Staff, former GIP Intern).

Andrea Habeck

Before long, Schmelz decided to pursue a career as a geologist, specializing in the study of marine, coastal, and estuarine sedimentation and its preservation in the geologic record. Psuty gave him a leg up by inviting him to stay on board as a research assistant and supporting his bid to pursue graduate studies at Rutgers University. Five years out from the GIP program, Schmelz is currently conducting his doctoral research.

Besides launching his career, Schmelz’s GIP internship with the National Park Service positioned him as a close observer of the coastal geomorphology of Sandy Hook and of other coastal areas of New Jersey and New York in the months before Hurricane Sandy. Schmelz was two months out of his internship when, on October 29, 2012, Hurricane Sandy pummeled the U.S. Atlantic coast. For developed areas along the coast, the storm was catastrophic, and the public lands where Schmelz had spent the summer collecting data saw vast changes across natural environments, as well as the destruction of structural resources like maintenance buildings, boardwalks, and paved roads.

After the storm, Schmelz remembers a feeling of unity and purpose among scientists and park staff as they set out into the parks to record the changes that the storm had wrought. Schmelz remembers, “we surveyed every site using each of our three primary methodologies to measure the changes that occurred as a result of the storm. We were being asked for the data. It gave me a sense that the work we were doing was meaningful and that I could help out the park and maybe the community in a time when there was a need for the information that we could provide.”

Park managers need scientific information about coastal environments in order to develop effective solutions for managing public lands, especially under conditions of rapid change and widespread instability. As an intern for the NPS Inventory and Monitoring Program, Schmelz contributed to research that tracks changes in shoreline position and adjacent coastal environments over long periods of time, measures how these natural resources changed as a result of Hurricane Sandy, and models how future storms, sea level rise, and other effects of climate change might affect coastal public lands in the future.

Sarah Gulick

Growing up, Katy Ames spent a lot of time exploring outdoors near her home in Glen Arm, Maryland. Her childhood home was “surrounded by trees and cattle and a lot of good rocks.” She remembers dragging her little brother and the neighborhood kids outside for adventures in the woods. Now, Ames jokes when she looks back on her childhood obsession with Jurassic Park, she supposes that her early aspirations are fulfilled by the work she does in Dr. Psuty’s Sandy Hook lab. Like Schmelz, Ames started out as a GIP intern working for the NPS Inventory and Monitoring Program, and before long, Psuty hired her to his team.

Before arriving in Psuty’s lab, Ames was relentless in pursuit of her dream to become a scientist. She voluntarily doubled down on chemistry and math classes in high school, exceeding all requirements. “I knew science was for me,” she says. “It fit who I wanted to be.”

Ames had no trouble drumming up worthwhile questions about the geology of the ocean floor and coast. As a graduate student, she immersed herself in theoretical marine geophysics. For her master’s thesis, she investigated the interaction of mid-ocean ridges and mantle plumes, found in the Earth’s interior. But these studies left Ames feeling out of touch with the natural world.

“I didn’t have that much field work,” she says. “It was all numerical modeling and data from satellites, so I would beg people to let me go in the field with them, just to get outside.”

Once she graduated, Ames was hungry for an experience that would allow her to be physically connected with the environment that she was studying, and she wanted to do research that had more immediate consequences and applications.

Sarah Gulick

“My master’s thesis was very theoretical,” she says. “I focused on mantle geodynamics, five kilometers under the water . . . It was cool to me, and it was impactful, but I wanted something that I could look at what I was studying, and I wanted to have more impact for more people.”

In the summer of 2015, as a GIP intern for the National Park Service in Psuty’s lab, Ames was thrust into field surveys several days a week. The field work gave her opportunities to be hands-on in research sites across Gateway NRA. She also had opportunities to exchange ideas and information with people on the beach who took an interest in what she was doing.

People who lived close to the study sites approached Ames when she was in the field. They were eager to ask what she was measuring and to share their observations and stories about Hurricane Sandy and its effects. The spontaneous exchanges helped Ames to understand, in a more nuanced way, how local communities in and around Sandy Hook understood and coped with the storm and its long-term consequences.

Even as she worked to collect precise data that could explain how Hurricane Sandy affected the shorelines, beaches, and dunes, Ames tuned in to some of the ways that her science might be perceived, valued, or used by coastal communities in the region.

As a GIP intern, having that sense of audience is important, because, besides collecting and processing data, Ames also worked with Psuty and his team to communicate findings for public and scholarly audiences alike. She helped to design figures and write reports and briefs that synthesized data and findings, and she composed, designed, and delivered presentations and posters at local, regional, and national conferences.

Katy Ames

Coastal areas are extremely dynamic, and they have many ephemeral features that are constantly changing as a result of wave action, wind, storm events, and sea level rise. When Schmelz and Ames looked at aerial photos of their study areas taken pre- and post-Hurricane Sandy, it was apparent, for example, that post-storm Sandy Hook—immediately after the storm—was missing some distinctive dune features.

Major storms can cause visible changes to dunes, demonstrating the inherent vulnerability of coasts. But vulnerability is not necessarily a negative quality, and it is only one part of the story. The vital processes that make coastal ecologies work include the natural movement of sediment across, over, and around shorelines, beaches, and dunes. And the formation, overwash, and re-formation of dunes is a necessary and inevitable condition of dynamic coasts.

There are multiple ways of understanding the movement of sediment, shoreline dynamics, and the changing physical geography of coasts. Psuty and his team monitor key coastal geomorphological features regularly, and they collect their data systematically, so that their studies are replicable year after year. They track trends and collect baseline information that allows them to recognize the difference between changes that may sustain the integrity of vital coastal systems in the long-term, and changes that are anomalous or even potentially hazardous.

NPS/Wickersty

In their roles as GIP interns, Ames and Schmelz worked under Psuty’s guidance to map the physical geography of shorelines, beaches, dunes, cliffs, and bluffs. Using high-accuracy GPS units, they mapped high-water lines. They also collected measurements of elevation along designated stretches of the coast, from dune to shoreline. Finally, they collected high-resolution information to calculate the volume of sediment contained at specific points along the shore. The data they collected will inform scientists, park managers, policymakers, and locals about precise changes in dynamic coastal systems, including whether, where, and to what extent sediment is moving, accumulating, or eroding. And with that knowledge, park managers can make fact-based decisions about how best to manage structural, natural, and cultural resources in public lands, now and well into the future.

Exposed areas of Gateway NRA, including the Jamaica Bay unit, are extremely vulnerable to inundation, and the research Ames and Schmelz contributed to has implications for managing these ocean shorelines. Meanwhile, the GIP program gives aspiring scientists, like Ames and Schmelz, a field-based experience that expands their understanding of scientific research and helps them connect their expertise with the shared problems of broader local and global communities.

For Schmelz, the GIP internship provided a breakthrough. Before the GIP Program, he had been drawn to the technical facets of research. He focused on methods, tools, and technologies, so much so that he sometimes overlooked broader issues at the heart of the matter. But now, he says, “I’ve grown to appreciate the process of discovering the important questions that need to be answered and try to figure out how to answer them.”

And Ames gained a renewed commitment to scientific inquiry. In the two years since her GIP internship, she has continued to work in Pstuy’s lab, where she feels a strong sense of fulfillment. “It’s a very important data set that we’re collecting, and not only for scientists,” she says, “but also for the park and for people that are designing infrastructure.” In addition to advancing her career and fulfilling her personal desires to get beyond the theoretical, to get outside, and to be actively involved in collecting data in the field, the GIP internship put Ames in a position to contribute to science that has direct consequences for “real life decisions,” something that promises rewards not only for the scientist, but also for coastal communities.

Written by Jamie Remillard & Caroline Gottschalk Druschke (SEAcomm URI)

Visit the Northeast Coastal and Barrier Network's website to learn more about monitoring ocean shoreline position and coastal topography, and some of the issues impacting our coastal parks!