Last updated: October 26, 2021

Article

Michael J. Heney: The Irish Prince

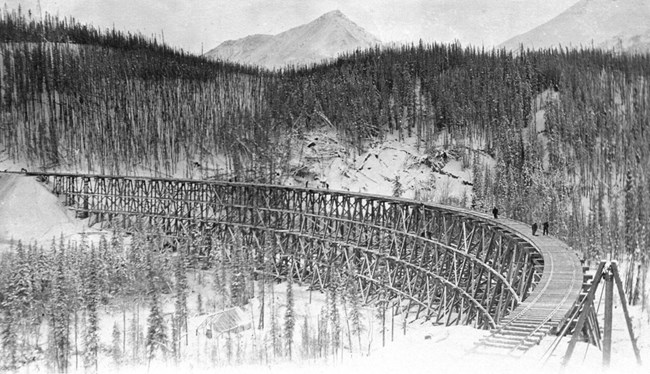

National Park Service, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, George & Edna Rapuzzi Collection, KLGO 59779u. Gift of the Rasmuson Foundation.

A trail, road, and tramway were developed in a span of a year to ease the congestion of people and pack animals that attempted this journey. All of these transportation systems failed; however, a successful transportation route was developed thanks to the ingenuity and expertise of Michael J. Heney, the “Irish Prince.”

Michael J. Heney was born in 1864 to Irish immigrant farmers in Ontario, Canada. At the young age of 14, he ran away from the family farm to work for the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) in British Columbia, Canada. An older brother found him and brought him home. He stayed in Ontario working on the farm until he was 17, when he left again to work for the CPR. Heney started working as a mule-skinner before he progressed to laying rails.

In 1883, he started working on a surveying crew in Frasier River, B.C., which he worked with for the next two years. His ultimate goal was to learn as much about the construction of railroads as possible. When the railroad was complete, he made the decision to pursue a degree in engineering so that he could become an independent contractor. After finishing school, he went back to work for the CPR. In 1896, he came to Alaska to work on a project at Anchor Point (located on the Kenai Peninsula), sparking his interest in the north.

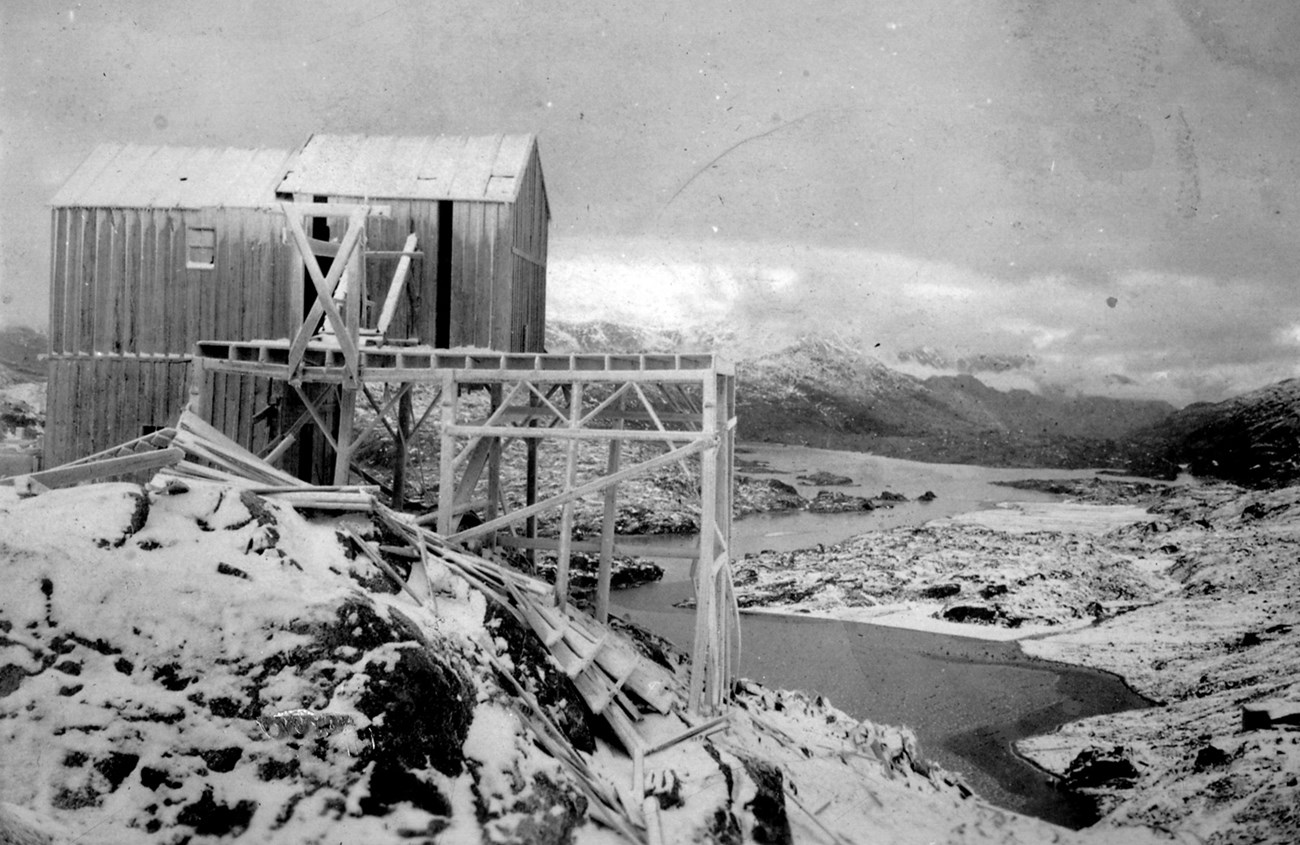

National Park Service, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, George & Edna Rapuzzi Collection, KLGO 57572. Gift of the Rasmuson Foundation.

A short time after the Anchor Point project, in March 1898, Heney traveled to Skagway, Alaska, to conduct a preliminary search of the White Pass Trail. He believed a successful railway could be constructed over the pass. By happenstance, Heney met two engineers from a bank in London, Close Brother and Company, who were assessing the pass to determine if a railroad was feasible. They had decided it was not.

Enter Heney, who convinced them otherwise.

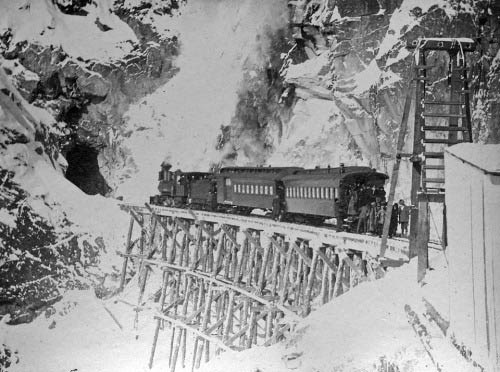

They developed a plan to construct the railway using a narrow gauge system, which was able to handle the steep terrain of the White Pass. Heney was initially labor foreman, but eventually became the contractor on record for the last two-thirds of the railways construction.

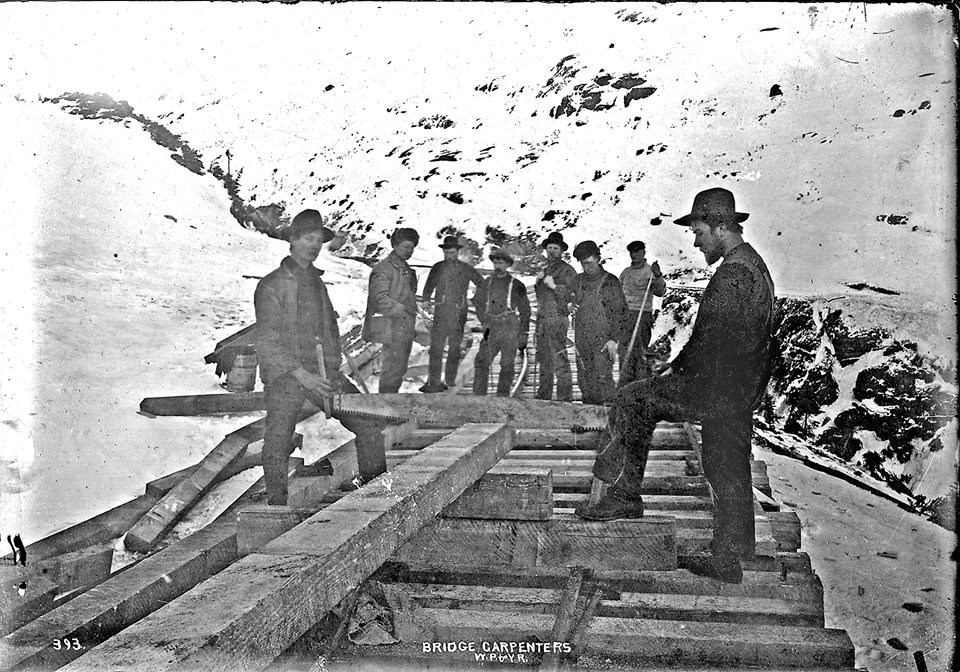

Image courtesy of British of Columbia Archives

On June 15, 1898, Michael Heney authorized the ground breaking of the White Pass and Yukon Route (WP&YR) Railway, beginning at Broadway in Skagway. Heney supervised a crew of a 1,000 men and set up crews that worked around the clock during the summer. He would travel between camps by horse to check progress; he set up a cot at every camp along the route for this purpose.

The construction itself was a dangerous feat. The placing of the route required steep grading, switchbacks, and blasting of rocks. He oversaw the construction through harsh winds, snowstorms, a labor strike, and the desertion of crews for the gold fields. Overall, Heney managed an estimated 35,000 workers who constructed the 110.6-mile railway in less than three years at the cost of $10 million. The WP&YR Railway, completed at Whitehorse, Yukon, Canada, on July 29, 1900, reconfigured the transportation network between Alaska and the Yukon.

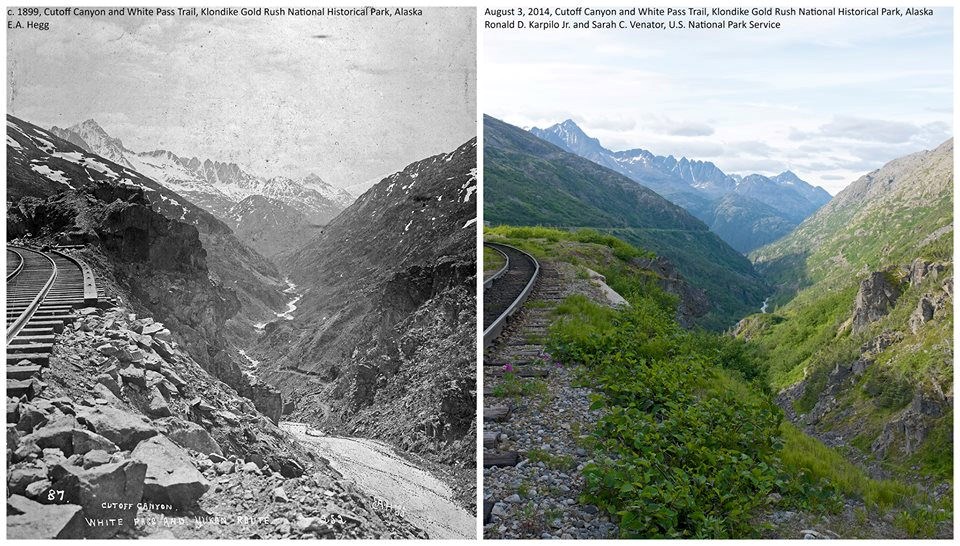

Left: Eric A. Hegg, Yukon Archives, ca. 1899; Right: Ronald D. Karpilo, Jr. and Sarah C. Venator, NPS, August 3, 2014

NPS Photo / Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve, Geoff Bleakley Collection

Michael Heney pursued another opportunity in the Copper River Valley in 1901 after completing the WP&YR Railroad. The Kennecott Copper Corporation was looking for a route to transport ore and supplies from their large mining operation at Kennecott Mines, Alaska. Heney surveyed the area, and determined that the best route was from Kennecott to Cordova. However, the Kennecott Copper Corporation did not agree and began establishing a different route.

Heney founded the Copper River Railway Company, and began construction on his railroad in April 1906 with the backing of the Close Brothers and Company. In the meantime, the Kennecott Copper Corporation began construction on their railway, originating in Valdez, Alaska. They soon realized their choice was not feasible, and hired Heney to complete the railway following his route. It was completed in 1909 as the Copper River and Northwestern Railroad.

Michael J. Heney’s railroad construction skills contribute to two of Alaska national parks, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park and Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve. Though the railroad is no longer extant in Wrangell-St. Elias NPP, visitors to the park travel along the historic railbed into the interior of the park, which terminates at Kennecott Mines National Historic Landmark.

Sources

Gilbert, Cathy, Paul White, and Anne Worthington. “Kennecott Mill Town Cultural Landscape Report,” Anchorage, AK: National Park Service, Alaska Regional Office, 2001.

Matthews, Laurie and Edward San Filippo. “White Pass Historic Transportation System Cultural Landscape Report-Draft,” Skagway, AK: National Park Service, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, 2017.

Minter, Roy. “HENEY, MICHAEL JAMES,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13. University of Toronto, 2003. Accessed February 2017. http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/heney_michael_james_13E.html.