Part of a series of articles titled The M'Clintock House & Women's Rights: Opportunities for Learning .

Article

The M'Clintock House & Women's Rights: Opportunities for Learning (3: The M'Clintocks and Women's Rights)

Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/97500106/

Before the Civil War (1861-1865), law, religion, and tradition severely limited the rights of and opportunities for American women. Nowhere in the country could they vote. In many states, once married they could not sign contracts, own property (even if they had inherited it), or control their own earnings. The husband received custody of children after a divorce, no matter his actions during marriage. Though women could hold certain jobs, most notably domestic work, most professions were closed to them. The percentage of girls who attended school trailed far behind the figure for boys. The first women's college, Mount Holyoke, opened only in 1837.

Most Americans of both sexes accepted, even supported, these conditions. They cited Biblical passages that a wife should be subject to her husband. They argued that women were more submissive, gentle, pious, and nurturing than men, leaving them poorly suited for the rough worlds of politics and business. Those same characteristics, however, made them perfect for the "domestic sphere" raising children, keeping the home, and serving their husbands' needs.

Explore the documents and images below to learn about how women like Mary Ann and Elizabeth M'Clintock challenged societal expectations for women.

The ideal of the perfect home was often far from reality. Financial necessity forced many women to work outside the home at the same time they were expected to handle most of the household responsibilities. Middle-class women who stayed home often found their lives frustrating and exhausting. Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who lived in the neighboring town of Seneca Falls and whose family had enough money to hire servants, wrote:

To keep house and grounds in good order, purchase every article for daily use, keep the wardrobes of half a dozen human beings in proper trim, take the children to dentists, shoemakers, and different schools, or find teachers at home, altogether made sufficient work to keep one's brain busy, as well as all the hands I could press into service.... My duties were too numerous and varied, and none sufficiently exhilarating or intellectual to bring into play my higher facilities. I suffered with mental hunger, which, like an empty stomach, is very depressing.1

Stanton was not the only woman who felt this way and many became activists to change their situation. Some women entered public spaces by voting, if they lived in one of the few states where women could vote. Others took part in religious movements. Some women fought to end slavery or change alcohol laws. Still, many of these women were limited by discrimination. In Stanton’s case, she and other female delegates were not allowed to take seats at the World Anti-Slavery Convention in 1840. The men blocked them. This bigotry helped direct Stanton’s energy toward women’s rights.

Stanton’s desire for gender equality grew in 1848 when she went to a tea party with activists and her future collaborators: Lucretia Mott, Martha C. Wright, Jane Hunt, and Mary Ann M’Clintock.

. The New York women talked about their frustrations and from that discussion the idea for the Seneca Falls Convention formed.

Stanton, M’Clintock, Mott, Wright, and Hunt planned the Seneca Falls Convention at Mary Ann M’Clintock’s family home over the next week. There, the women wrote the famous Declaration of Sentiments. The document outlined their views on the role of women in society. Stanton later said about the week, “what a time we hadwriting it! We looked over the declarations of societies we could find, but none touched our case, until at last, someone suggested our Fathers of 1776.”2

From July 19-20, soon after they wrote the Declaration, the women held the First Women’s Rights Convention at Seneca Falls. More than 300 people went to Seneca Falls. Most of the attendees were women. About forty men joined the convention, as well, including African American abolitionist Frederick Douglass. The M’Clintock family also played a part at the event. Thomas M’Clintock was convention president. Mary Ann’s daughter, Elizabeth M'Clintock, served as secretary.

At the Convention, Stanton presented their concerns and demands. For two days, the convention participants discussed the rights women had and the rights they still had to achieve. Through these discussions, they edited and developed a final version of the Declaration of Sentiments. Finally, 68 women and 32 men signed their names to the document. At least half of the people who signed were from Waterloo, including the M'Clintocks and the Hunts. The members then debated twelve resolutions that called for equality for women in different areas of American society and culture, including the right to vote in public elections. This debate among women’s rights activists showed just how deep-rooted beliefs about women’s place away from politics were. Even among these delegates, a resolution calling for a woman’s right to vote barely passed.

Mary Ann and Elizabeth M’Clintock’s house is part of the Women’s Rights National Historical Park (a National Park Service unit). From her historic home, we can study the meaning of a “woman’s place” and how it was challenged in the past. Ironically, it was from a humble place, a symbol of women’s separation from the public, that the women’s rights movement demanded the nation take notice.

Discussion Questions:

1. In what aspects of life were American women in the mid-19th century restricted? How did people justify these limits?

2. Do you think it mattered that the five women who organized the First Women's Rights Convention already knew each other? Why or why not?

3. How do you think the organizers acquired the skills they needed to make the conference a success?

4. Why do you think many of the people who were interested in women's rights were also committed to the abolition of slavery?

The 1848 Declaration of Sentiments lists the rights women believed they were entitled to, including suffrage (or voting) rights.

When, in the course of human events, it becomes necessary for one portion of the family of man to assume among the people of the earth a position different from that which they have hitherto occupied, but one to which the laws of nature and of nature's God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes that impel them to such a course.

We hold these truths to be self-evident; that all men and women are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness; that to secure these rights governments are instituted, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed. Whenever any form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the right of those who suffer from it to refuse allegiance to it, and to insist upon the institution of a new government, laying its foundation on such principles, and organizing its powers in such form as to them shall seem most likely to effect their safety and happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly, all experience hath shown that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves, by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same object, evinces a design to reduce them under absolute despotism, it is their duty to throw off such government, and to provide new guards for their future security. Such has been the patient sufferance of the women under this government, and such is now the necessity which constrains them to demand the equal station to which they are entitled.

The history of mankind is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations on the part of man toward woman, having in direct object the establishment of an absolute tyranny over her. To prove this, let facts be submitted to a candid world.

He has never permitted her to exercise her inalienable right to the elective franchise.

He has compelled her to submit to laws, in the formation of which she had no voice.

He has withheld from her rights which are given to the most ignorant and degraded men - both natives and foreigners.

Having deprived her of this first right of a citizen, the elective franchise, thereby leaving her without representation in the halls of legislation, he has oppressed her on all sides.

He has made her, if married, in the eye of the law, civilly dead.

He has taken from her all right in property, even to the wages she earns.

He has made her, morally, an irresponsible being, as she can commit many crimes, with impunity, provided they be done in the presence of her husband. In the covenant of marriage, she is compelled to promise obedience to her husband, he becoming, to all intents and purposes, her master - the law giving him power to deprive her of her liberty, and to administer chastisement.

He has so framed the laws of divorce, as to what shall be the proper causes of divorce; in case of separation, to whom the guardianship of the children shall be given, as to be wholly regardless of the happiness of women - the law, in all cases, going upon the false supposition of the supremacy of man, and giving all power into his hands.

After depriving her of all rights as a married woman, if single and the owner of property, he has taxed her to support a government which recognizes her only when her property can be made profitable to it.

He has monopolized nearly all the profitable employments, and from those she is permitted to follow, she receives but a scanty remuneration.

He closes against her all the avenues to wealth and distinction, which he considers most honorable to himself.

As a teacher of theology, medicine, or law, she is not known.

He has denied her the facilities for obtaining a thorough education - all colleges being closed against her.

He allows her in Church as well as State, but a subordinate position, claiming Apostolic authority for her exclusion from the ministry, and with some exceptions, from any public participation in the affairs of the Church.

He has created a false public sentiment, by giving to the world a different code of morals for men and women, by which moral delinquencies which exclude women from society, are not only tolerated but deemed of little account in man.

He has usurped the prerogative of Jehovah himself, claiming it as his right to assign for her a sphere of action, when that belongs to her conscience and her God.

He has endeavored, in every way that he could to destroy her confidence in her own powers, to lessen her self-respect, and to make her willing to lead a dependent and abject life.

Now, in view of this entire disfranchisement of one-half the people of this country, their social and religious degradation, - in view of the unjust laws above mentioned, and because women do feel themselves aggrieved, oppressed, and fraudulently deprived of their most sacred rights, we insist that they have immediate admission to all the rights and privileges which belong to them as citizens of these United States.

In entering upon the great work before us, we anticipate no small amount of misconception, misrepresentation, and ridicule; but we shall use every instrumentality within our power to effect our object. We shall employ agents, circulate tracts, petition the State and national Legislatures, and endeavor to enlist the pulpit and the press in our behalf. We hope this Convention will be followed by a series of Conventions, embracing every part of the country.

Firmly relying upon the final triumph of the Right and the True, we do this day affix our signatures to this declaration.

Discussion Questions:

1. On what document was the Declaration of Sentiments based? Why do you think the writers chose that as their basis?

2. What are some of the abuses listed in the Declaration? What rights does this list suggest the women at the convention would like to have had?

3. Only one-third of the 300 people at the convention signed the Declaration of Sentiments. Why do you think the other 200 refused? Would you have signed it? Why or why not?

4. What do you think about the next-to-last paragraph? Does this plan seem to you to be a good one for obtaining change? Why or why not?

Learn more about the Declaration of Sentiments.

The life of Elizabeth M'Clintock (1821-1896) in the years following the Seneca Falls Convention illustrated both the challenges and opportunities for American women in the second half of the 19th century. Immediately after the meeting clergymen and newspapers attacked its organizers and supporters. Elizabeth Cady Stanton wrote some years later, "All the journals from Maine to Texas seemed to strive with each other to see which could make our movement appear the most ridiculous."3

These attacks had only a limited effect, however. Though some of the women who had signed the Declaration decided to withdraw their names, most continued to support the document and the ideas it promoted. The newspaper stories often had the opposite effect their authors intended, because these reports became a way that people learned about the arguments over women's rights. Soon other women’s rights conventions took place around the country, and similar meetings continued through the rest of the century.

M'Clintock and Stanton worked hard to ensure that the public did not hear only from their opponents. Together they tried to counter every argument that was presented against women's rights by writing articles for newspapers from Seneca Falls to New York City, responding to critical ministers, and appealing to the state legislature. They encouraged other women to organize themselves and helped set up women's rights meetings in the Burned-Over District towns of Auburn, Waterloo, Farmington, Rochester, as well as a second one in Seneca Falls.

In the fall of 1849 the two women tried to improve opportunities for women in a more personal way. Earlier in the 1840s, Lucretia Mott's son-in-law Edward M. Davis had offered M'Clintock an apprenticeship in his silk trading firm in Philadelphia. M'Clintock thought he genuinely wanted to give her the opportunity to follow the "spirit of enterprize." M'Clintock and Stanton wrote to Mott to ask if she could have her son-in-law give M'Clintock a job, or at least find openings at another company.

When his answer came a month later, it was far from what M'Clintock had expected. Davis was not willing to offer her a job, but said his decision had nothing to do with her sex. He explained that because an apprenticeship involved years of menial work at low pay, he would not hire anyone already 28 years old (M'Clintock's age at the time). In addition, Davis's lead salesman Rush Plumly wrote that M'Clintock had no experience in this kind of work nor did she bring with her any capital (wealth) to invest in the business.

M'Clintock recognized that the problems Davis and Plumly pointed out had little to do with her personally. They were instead illustrations of the barriers women faced when trying to enter business. She was considered too old and lacked the appropriate experience precisely because women had been excluded from most types of work. She lacked capital for the same reason and because of the laws which limited the property women could keep in their own names.

Not everyone in Davis's firm was so business-like in their reaction to M'Clintock's request. He had passed around her letter to his employees, all of whom were men. Their responses were collected and sent back to her via Lucretia Mott.4 One clerk argued that public prejudices would hurt the company's business: "It would be 'hostile' to the interests of the house in the present state of public sentiment. While all in the company might regret the existence of the senseless objections to woman so participating in commerce and politics, they are not strong enough financially to stem it. The results of such absurd prejudice would hurt the company's business and it would diminish trade." The firm had reason to worry: supporters of slavery, for example, at times threatened to close down merchants who campaigned for abolition.

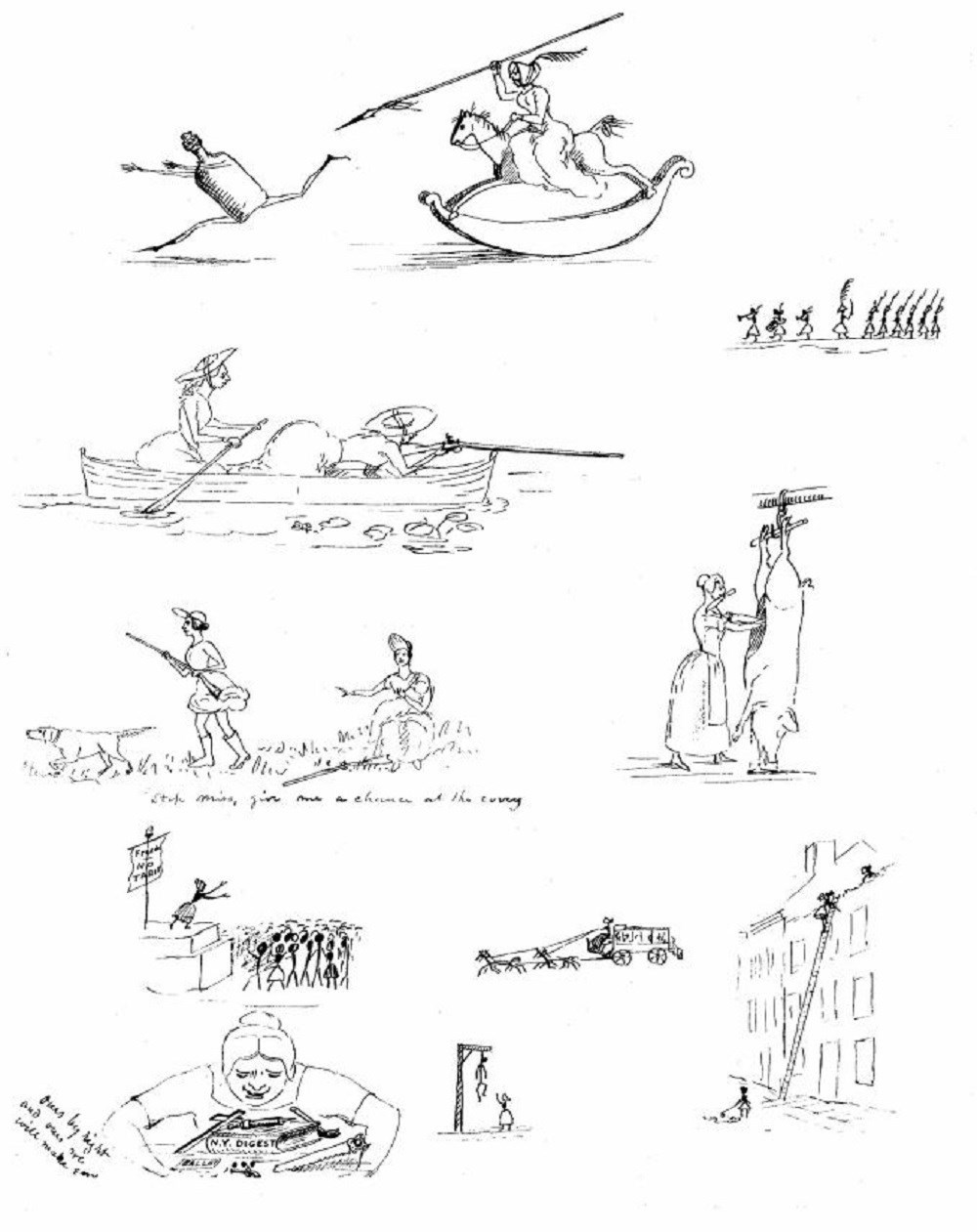

Other workers at the company based their objections on the "nature" of women. One of the bookkeepers argued that "The sphere of women has its circumference in domestic and social duties. Women are not naturally strong enough in Mind, to conduct such a concern." Several of the men even included cartoons making fun of women like M'Clintock.

M'Clintock and Stanton were dismayed when they received the letters and the cartoons. M'Clintock found the comments particularly painful since many of the men shared her religion, which supposedly supported equal rights, and her interest in social reform. She responded by drawing her own cartoons and by writing a play in which she used a fictionalized version of her experience to reveal her support for a society which gave women equal opportunity and status.

In 1852, M'Clintock married Burroughs Phillips, a lawyer whose brother was minister of the Methodist church in which the convention had been held. Phillips actively supported the women's rights movement, joining his wife as an organizer of a women's rights convention in Syracuse. In April 1854, however, Phillips fell from his carriage and received a blow to the head that doctors could not treat. After less than two years of marriage, Elizabeth M'Clintock became a widow.

A series of changes took place in her life over the next decade. In 1856 her family decided to move back to Pennsylvania in the hope of finding opportunities for their children so the family could continue to live near one another. The M'Clintocks also continued their commitment to abolition, an increasingly contentious issue through the 1850s.

It was during the Civil War that Elizabeth M'Clintock finally had the opportunity to pursue her interest in business. In 1861 she opened her own store in downtown Philadelphia; her father apparently offered her the same kind of financial assistance he had earlier given her brother. Her shop served middle-class women, offering items such as hosiery, gloves, and shawls. The store was successful enough that M'Clintock developed the reputation of a solid, responsible businesswoman, and she earned enough that she could retire in 1885 to a home in New Jersey. She died in 1896 at age 75, a woman whose life showed both the opportunities women created for themselves in 19th century America and the limits they faced.

Discussion Questions:

1. How did the newspapers affect people's views of women's rights after the Seneca Falls convention?

2. What experiences did Elizabeth M'Clintock have that might have made her interested in running her own business?

3. What reasons did the men in Davis's firm give for denying M'Clintock's application?

4. Given that Davis's firm took a strong stand against slavery, was it reasonable for his employees to worry about how having a female employee would hurt business? Why or why not?

Discussion Questions:

1. What jobs or skills do these cartoons show women performing? Why do you think Elizabeth chose to draw these scenes? What point do you think she wanted to make?

2. How would you describe the clothing the women are wearing? Why do you think Elizabeth did not have them dress more like men?

3. Do you think these images would have changed the minds of people in the middle of the 19th century? Why or why not?

1. Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Eighty Years & More: Reminiscences, 1815-1897 (New York: T. Fisher Unwin, 1898; reprint, Schocken Books, 1971).

2. Stanton, Revolution 17 September 1868, 162.

3. Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Eighty Years More: & Reminiscences, 1815-1897 (New York: T. Fisher Unwin, 1898; reprint, Schocken Books, 1971), 149.

4. "Abstract of the discussion among the employees of E.M. Davis & Co. upon the expediency and right of admitting women into the store," 2 October 1849, Garrison Family Papers, Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College.

The first reading was compiled from Andrea Constantine Hawkes "'Feeling a Strong Desire to Tread a Broader Road to Fortune:' The Antebellum Evolution of Elizabeth Wilson M'Clintock's Entrepreneurial Consciousness,"(Master's thesis, University of Maine, 1995); Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Eighty Years & More: Reminiscences, 1815-1897 (New York: T. Fisher Unwin, 1898; reprint, Schocken Books, 1971); and Sandra S. Weber,Special History Study: Women's Rights National Historical Park, Seneca Falls, New York (Washington: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1985).

The last reading was compiled from Andrea Constantine Hawkes, "'Feeling a Strong Desire to Tread a Broader Road to Fortune:' The Antebellum Evolution of Elizabeth Wilson M'Clintock's Entrepreneurial Consciousness," (Master's thesis, University of Maine, 1995); Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Eighty Years & More: Reminiscences, 1815-1897 (New York: T. Fisher Unwin, 1898; reprint, Schocken Books, 1971).

Last updated: August 27, 2019