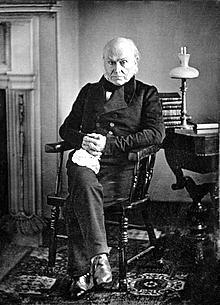

“Rather more proud than they have reason to be” —future president John Quincy Adams

Public Domain.

Future president John Quincy Adams remained unconvinced that America had gained anything by fighting the War of 1812. Writing privately to his father in 1816, he grumbled that many Americans were “rather more proud than they have reason [to be]...”

Adams’ stinging assessment carried the ring of truth; American failures in the conflict were as pronounced as its triumphs. Most prominent was the disastrous attempt to conquer Canada. Many Americans went to war expecting to acquire Canada with little trouble, only to discover that effort thwarted repeatedly.

There were a number of reasons for the failure to take Canada. The Madison Administration and leading Republicans never came to a precise understanding over how to mount the invasion. The lack of purposefulness led to scattered, uncoordinated campaigns across the expansive Upper Canadian front.

The attempts on Canada also taxed American supply lines. The far-flung campaigns made it nearly impossible to keep troops adequately supplied—and without reliable provisions, discipline and morale became enormous problems. American troops, fashioning themselves as “liberators,” resorted to the looting and destruction of Upper Canadian property, frittering away any reserves of good will among the populace in the process.

Nor were American generals up to the task of mounting a large-scale invasion. Brigadier General William Hull was perhaps the most infamous; fearing Indian atrocities and without consulting any of his senior officers, Hull surrendered the garrison of Fort Detroit without a fight. Court-martialed for neglect of duty and cowardice, Hull remains the only American general officer to be condemned to death (President Madison accepted the court’s recommendation to spare Hull’s life in view of his Revolutionary War service).

Other generals fared little better in their attempts on Canada. Major General Henry Dearborn proved ill-suited for high command; nicknamed “Granny” by his men, Dearborn’s failure to follow up after the seizure of Fort George allowed British forces to escape, an act for which he was eventually relieved of command. Dearborn’s replacement, Major General James Wilkinson, was variously described as an “unprincipled imbecile,” and a “villain to the very core.” Wilkinson and his chief subordinate loathed one another so much that they refused to cooperate on the battlefield. Wilkinson’s 1813 campaign to capture Montreal collapsed almost from the outset; Wilkinson ordered his men back into winter quarters, where they suffered under brutally cold conditions. The following spring, as his offensive again bogged down, Wilkinson was relieved of command and later court-martialed, only to be acquitted of all charges.

The checkered record of some of its top commanders, however, did not linger in the public memory, and only a few years after the conclusion of hostilities many Americans had begun to remember a more triumphant version of the war—one that, as John Quincy Adams pointed out, did not necessarily correspond to the historical reality.

Last updated: May 24, 2016