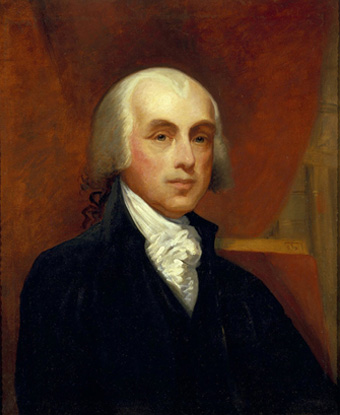

While acknowledging his genius as a political theorist, historians are often less than enthusiastic about James Madison’s performance as a wartime President.

"Our President has not those commanding talents, which are necessary to control those about him." John C. Calhoun

National Park Service

James Madison was a brilliant political thinker and one of the great intellectuals of his age. But he could be a colorless and feeble wartime leader. Prone to react to events rather than anticipate them, Madison seemed incapable of acting decisively in his role as commander in chief.

Madison’s preferred management style was characterized by deference to others, including his cabinet and senior military commanders. The president tended to accept infighting among his rancorous cabinet members instead of decisively resolving disagreements. Often the Administration seemed at cross-purposes with itself. The chief executive appeared to react to his cabinet rather than lead it.

Madison was also inclined to give way to his generals. Given the astounding ineptness of some of his senior commanders, including the elderly and unfit William Hull, the excessively cautious Henry Dearborn, and the wholly unprincipled James Wilkinson, Madison’s approach to management proved particularly ruinous to the Administration’s direction of the war against Canada.

Madison also had to contend with some weaknesses in the fledgling American government. Madison was committed to waging the war in a Republican manner—but Madison’s ideas regarding small government, light tax burdens, and weak executive leadership were frequently at odds with the requirements for effective warmaking. The small War Department bureaucracy was much too small to recruit, finance and supply a large-scale war.

Federalist opposition to the war sometimes obscured the fact that congressional Republicans were also a splintered lot. In fact, after Madison outlined his war aims, one-quarter of all Republicans either voted against or abstained from the vote to declare war. When news arrived later in the summer of 1812 that the British had withdrawn their restrictions on neutral shipping and Madison refused to back down from his calls for war, Republican unity crumbled further. Over time, Republican malcontents in Madison’s own part would repeatedly challenge his political mandate for war.

Today, James Madison’s insistence on fighting a Republican war based on republican principles may seem hopelessly naïve. But by fighting the War of 1812 on his own terms, many contemporary Americans believed Madison had put a uniquely hopeful stamp on the war’s legacy. Indeed, Federalist John Adams remarked in 1817 that Madison had “acquired more glory, and established more Union than all three of his predecessors.”

Last updated: May 24, 2016