Last updated: January 6, 2026

Article

Isaac S. Hawkins: Prisoner of War

Courtesy Boston Athenaeum

When hundreds of thousands of soldiers enlisted in the American Civil War—by volunteering or by conscription—they risked more than just physical harm and death on the battlefield. Throughout the war, thousands of soldiers found themselves trapped, overrun, or unable to retreat due to wounds during battles. At the mercy of their captors, they surrendered as prisoners of war. For the soldiers of the 54th Massachusetts and other Black regiments, this fate provoked great worry. In addition to all the threats they shared along with their White counterparts, Black soldiers faced retaliation by their Confederate captors. The Confederacy considered Black Union solders as insurrectionists attempting to destroy the social and racial order. In General Orders Number 111, Confederate President Jefferson Davis stated that "all negro slaves captured in arms be at once delivered over to the executive authorities of the respective States to which they belong to be dealt with according to the laws of said States." This order effectively threatened enslavement or outright execution. Even White officers of Black regiments faced these extra risks. According to the orders, "all commissioned officers of the United States when found serving in company with armed slaves in insurrection against the authorities of the different States of this Confederacy" faced possible execution.1

In response to the Confederacy, President Abraham Lincoln issued General Order 233. This order threatened reprisal for any maltreatment against Black troops.2 This prompted the Confederacy to cease the prisoner exchange program. In the eyes of the Confederacy, in their fight to preserve the institution of slavery, one Black soldier did not possess equal value to a White soldier. As a result, their policies forced prisoners of war into extended imprisonment at prisoner of war camps.3

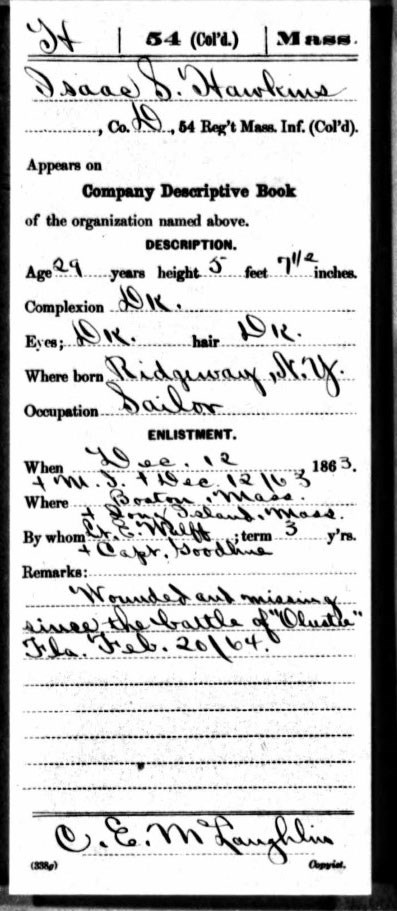

National Archives, Compiled Military Service Records of Volunteer Union Soldiers Who Served with the U.S. Colored Troops, 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment (Colored); Microfilm Serial: M1898; Microfilm Roll: 19

Despite these risks, men such as Isaac S. Hawkins enlisted as a private in the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment on December 12, 1863. Other than his birthplace of Ridgeway, New York, not much else is known about Hawkin's early life. The 1860 Federal census identified Hawkins as a "Mulatto" man and listed him as a day laborer. At that time, he lived with his wife Sarah and their daughter.4 Hawkins enlisted in Medina, New York, at the age of 29.5

After enlisting, Hawkins became of member of Company D. Hawkins joined the regiment in time for General Quincy Gilmore's invasion of Florida to stop Confederate supply routes. Hawkins and the 54th arrived at the Battle of Olustee late in the day on February 20, 1864. They arrived as Brigadier General Truman Seymour and his men began their retreat under fire. The 54th Massachusetts Regiment, alongside the 35th United States Colored Troops, protected the Union retreat from Confederate attack.6 While they successfully stopped the Confederate troops from advancing, the Union forces suffered heavy casualties—nearly twice as many as the Confederates.7 During the battle, Confederate soldiers captured many retreating men, including Isaac S. Hawkins. Whether by luck or cooler heads, Confederate forces ultimately treated Hawkins and many other captured Black soldiers as prisoners of war. In chaos of battle, men attempting to surrender were not always safe from effective execution. Furthermore, the long march under captivity deep in a land of slavery proved fraught with risks for Black men.

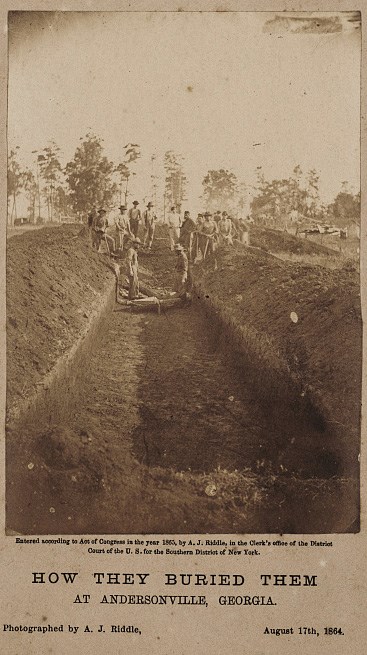

Prisoners from Olustee ended up in a new prisoner of war camp in Andersonville, Georgia. Hawkins and his fellow soldiers became some of the first Black prisoners of war at Andersonville.8 Though Hawkins did not leave an account of his experiences at Andersonville, his fellow prisoners of war witnessed first-hand what Hawkins endured. The testimony of Frank Maddox, a fellow Union soldier, gives the most detailed account of what Hawkins experienced at Andersonville:

Captain Wirz [the Andersonville commandant] hauled back and knocked [Hawkins] to the side of the tent and told [a guard] to take him, strip him, and give him five hundred lashes, calling him a ‘damned Yankee son of a bitch.’ They gave him two hundred and fifty lashes. The sergeant lied…and claimed that he gave him the full five hundred. [Hawkins] was then loosed and taken to the blacksmith shop, and had about two feet of chain put on him, and was sent to the graveyard to work, being told that if he stopped five minutes during the day he would get two hundred and fifty more. The man was whipped on the bare back.9

It is unknown exactly why Hawkins faced this brutal punishment. Witnesses at a later trial against Wirz gave a variety of different stories on why this occurred. What is consistent in their accounts, however, is that Isaac Hawkins received two hundred and fifty lashes, out of five hundred, by order of the Andersonville commandant, Captain Wirz.

This account is all that remains of Hawkins’ specific experience at Andersonville. According to Maddox, "The colored prisoners were in a gang by themselves…They were treated in no other way differently from the white soldiers."10 This means that to understand the rest of Hawkins' experience at Andersonville, all one has to do is look at the recorded experiences of his fellow prisoners of war.

Courtesy Library of Congress.

John L Ransom, another prisoner at Andersonville arrived less than a month after Hawkins. He kept a detailed daily record of his experiences there. The amount of food and the low number of prisoners surprised Ransom at first, especially compared to the worse conditions he faced at other prisons.11 Yet within two months he documented a different story. By the time construction of Andersonville finished, hundreds of new prisoners arrived almost daily. With more men, conditions worsened. The already limited water supply became contaminated and food rations grew smaller with each passing day. Men built shelters out of whatever they could find. These squalid conditions led to increasing death rates.12 Those who managed to survive Andersonville declined into ghosts of their former selves. Pictures taken of men after the liberation of Andersonville show emaciated men with their bones and joints completely visible under their skin. Despite these horrid conditions, Hawkins and many others survived this most infamous prisoner of war camp of the Civil War.

Hawkins remained at Andersonville for over a year until an exchange on March 4, 1865 at Goldsboro, North Carolina. From here, Hawkins moved to a parole camp in Annapolis, Maryland, and eventually mustered out of service on June 20, 1865.13

After the war, Hawkins returned to Ridgeway where he lived with his wife Sarah and their three daughters.14 By 1870, Hawkins moved to Washington D.C. where he remained for the rest of his life.15 Sometime between 1865 and 1870 his wife Sarah passed away. On December 7, 1880 he remarried Ella M. Nolen.16 In Washington D.C., Hawkins worked as a cook, and Ella worked as a washerwoman.17 Hawkins passed away on August 25, 1902. Today, Issac S. Hawkins is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.18

Footnotes

- Miller. Steven F., “Proclamation by the Confederate President: General Orders, No. 111,” Freedmen.umd.edu, Freedmen and Southern Society Project at the University of Maryland, August 3, 2020, http://www.freedmen.umd.edu/pow.htm

- “Black Soldiers in the U.S. Military During the Civil War,” National Archives and Records Administration, September 1, 2017 https://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/blacks-civil-war

- Pettijohn, Don, “African Americans at Andersonville,” Nps.gov/ande, National Park Service, February 2006, https://www.nps.gov/ande/learn/historyculture/african_americans.htm

- Year: 1860; Census Place: Ridgeway, Orleans, New York; Page: 878, Family History Library Film: 803836. Accessed via Ancestry.com

- Hawkins, Isaac S., Compiled Military Service Records of Volunteer Union Soldiers Who Served with the U.S. Colored Troops, 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment. The National Archived at Washington, D.C., Accessed via Ancestry.com

- Emilio, Luis F., A Brave Black Regiment: History of The Fifty-Fourth Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry 1863-1865, (Boston: The Boston Book Company, 1891), 171

- Emilio, Luis F., A Brave Black Regiment, 172

- Andersonville National Historic Site, “History of the Andersonville Prison,” National Park Service, April 14, 2015, https://www.nps.gov/ande/learn/historyculture/camp_sumter_history.htm

- United States Government Serial Set, Col. 1391, United States Government Printing Office, 1869, 117

- ibid.

- Ransom, John L., Andersonville Diary: Escape and List of the Dead, with Name, Co., Regiment, Date of Death and No. of Grave in Cemetery,(John L. Ransom: 1881), 42-43, https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=wH_hAAAAMAAJ&hl=en

- Ransom, John L., Andersonville Diary, 46-48.

- Hawkins, Isaac S, U.S., Civil War Soldier Records and Profiles, 1861-1865. Accessed via Ancestry.com

- Census for the state of New York, 1865, Accessed via Ancestry.com

- Year: 1870; Census Place: Washington Ward 4, Washington, District of Columbia: Roll: M593_124; Page: 866B; Family History Library Film: 545623. Accessed via Ancestry.com

- District of Columbia, Complied Marriage Index, 1830-1921, Accessed via Ancestry.com

- Year: 1860; Census Place: Washington, Washington, District of Columbia, District of COlumbia; Roll: 124; Page: 39D; Enumeration District: 102. Accessed via Ancestry.com

- Hawkins, Issac S., FindAGrave.com, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/49200343/isaac-s-hawkins