Last updated: May 20, 2024

Article

Hawaiian Presence at Fort Vancouver National Historic Site

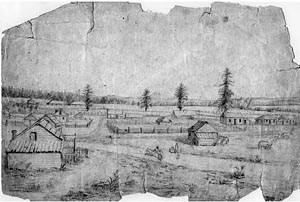

NPS photo.

Fort Vancouver, as the colonial “Capital” of the Pacific Northwest in the 1820s-1840s, supported a multi-ethnic village of 600-1,000 occupants. A number of the villagers were Hawaiian men who worked in the agricultural fields and sawmills of the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) operations. Identification of Hawaiian residences and activities has been an important element of studies of Fort Vancouver National Historic Site, Vancouver, Washington, since the 1960s.

Kauanui (2007:154) calls for a “broad research agenda that accounts for Hawaiian movements in their respective contexts of conditions, periods, reasons, and desires, to allow us to better account for Hawaiian presence on the North American continent.” Her call is to counter attempts to minimize or alter modern Hawaiian cultural identity and to better define the Hawaiian diaspora history. Research on fur trade Hawaiians dispels the notion that Hawaiian history is limited to Hawaii and allows us to better contextualize the broader issues of fur trade identity and social transition in the Pacific Northwest associated with indigenous, fur trade, and American immigrant eras (e.g., Philips 2008; Klimko 2004).

This paper discusses Native Hawaiians at Fort Vancouver, and explores the material evidence of their lives. In it, I raise questions regarding the identity of Hawaiians as revealed in the material culture and documentary record of the Fort Vancouver village. Further, I present the rationale for an expanded exploration of the village to better define the uses of the landscape to augment other ongoing studies of architecture, ceramics, tobacco pipes, glass vessels, and other archeological data.

Hawaiians at Fort Vancouver

“We had eight Sandwich Islanders amongst the crews, who afforded great amusement by a sort of pantomimic dance accompanied by singing. The whole thing was exceedingly grotesque and ridiculous, and elicited peals of laughter from the audience . . . The next day the men were stupid from the effects of drink, but quite good-tempered and obedient; in fact, the fights of the previous evening seemed to be a sort of final settlement of all old grudges and disputes” Paul Kane July 2-3, 1847 (Kane 1859: 258-259).

Paul Kane’s 1847 description of a fur brigade regale, two nights out of Fort Vancouver, punctuates a curious fact of the colonial period of the Pacific Northwest: Native Hawaiians were present in significant numbers. In the party that Kane accompanied, Hawaiians made up over 10% of the voyageurs. Rogers’ (1993) analysis suggests that the population of Hawaiians at Fort Vancouver ranged as high as 138 in 1844, approximately 30% of the population (see also Towner 1984). Hussey (1976:305) suggests that 50-60 lived permanently in the Fort Vancouver Village, with many others distributed at the mills, farms, and other posts and stations of the Department. Beechert and Beechert (2005) suggest the total number of Native Hawaiians on the Columbia River was between 300 and 400.

Kane’s description, above, also indicates that Hawaiians were part of the voyageur fur brigades and that they retained and, at times, publically displayed the hula. This raises some interesting questions regarding identity and ethnicity within the culture of the fur trade engagé, or fur trade worker, in the Pacific Northwest.

Fort Vancouver (1825-1860) was the HBC headquarters, supply depot, and cultural heart of the Columbia Department, which stretched across the Pacific Northwest from the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Ocean and from Mexican California to Russian Alaska (Erigero 1992; Hussey 1957; Wilson and Langford 2011). The fort and village population was the largest concentration of colonial people between New Archangel and Yerba Buena prior to the wave of American immigrants that came over the Oregon Trail in the mid-1840s. At its height in the 1830s and 1840s, the village population approached 1,000 people.

The large numbers of engagés at Fort Vancouver reflected the need to supply the many fur trade posts and fur brigades of the Department, but also reflected the diverse economy of the post. Besides being specialists in blacksmithing, coopering, tinning, and carpentry, significant numbers of personnel were utilized in growing wheat and other crops on the hundreds of acres under cultivation at the post and outlying farms; the raising of thousands of head of cattle, sheep, and pigs; and the salting of salmon at the fort’s salmon store. Likewise, a grist mill and lumber mill were established about five miles up the river, with wood products exported as far away as South America.

Descriptions of the village suggest that there were between 40 and 60 houses, built in a variety of architectural styles, with outbuildings, corrals, fenced gardens, roads, trails, and other features (Hussey 1976: 217-218; Thomas and Hibbs 1984: 45-47; Mullaley 2011). The HBC Riverside Complex, to the south of the village, included a salmon storehouse, boat works, tannery, cooperage, piggeries, stables, and a hospital (Erigero 1992:157-162).

Company management, and most likely other people at the fort, treated Hawaiians as a distinctive class or “other.” Many Hawaiians exhibited body and facial tattooing, and all spoke a language that was unintelligible to the other people living in the village. Physical separation of the Hawaiian houses from others at Fort Vancouver is suggested by William F. Crate, the millwright, who testified that there were streets for Hawaiians, French-Canadians, and Englishmen and Americans (Hussey 1957). Unlike contracts with members of other ethnic groups, many of the labor contracts between the HBC and Hawaiians specified that Hawaiian workers were to be returned to Hawaii at the expiration of their contracts. Another piece of evidence for the differential treatment of Hawaiians is the hiring of William Kaulehelehe, a Hawaiian Methodist preacher, who was brought in to minister to the Hawaiians of the village in 1845, and to help restrain the “corruptions” of the Hawaiians, including drinking, fighting, and gambling (Beechert and Beechert 2005:10; Hussey 1976:305-307).

It appears that most of the Hawaiians hired by the HBC were of the Hawaiian commoner class (maka'ainana). That there are some difficulties in assessing exactly what Hawaiian occupations were in the fur trade is illustrated in the outfit records for 1845, where most of the identifiable Hawaiians at the Vancouver Depot (Fort Vancouver) were identified solely as “laborer,” exceptions being “Spunyarn,” who was a cooper, and William Kaulehelehe, the Hawaiian preacher, who was referred to as a “teacher” (HBC Archives: B.223/d/162). Hawaiians primarily served as canoe middlemen (paddlers, but not bowmen or sternmen), sailors, farmers, and woodworkers (Rogers 1993; Towner 1984; Hussey 1957; Beechert and Beechert 2005). Some specialized as shepherds, sawyers, cooks, coopers, and woodcutters/stokers (for the Beaver steamship).

In addition to Hawaiians, the village was the home of a surprisingly diverse community of Fort Vancouver’s working class employees and their families, including French Canadians, Scots, English, Métis, and Native Americans representing tribes from across the North American continent (Erigero 1992; Hussey 1957; Thomas and Hibbs 1984). Seasonally, trapping parties (called “Brigades”) would deliver furs to the fort and to refit, which would swell the population of the village.

Many people of the fur trade spoke languages that were not intelligible to their comrades and exhibited unique racial and ethnic qualities. George Simpson (1847:107-108) called his bateau-load of people on the lower Columbia “the prettiest congress of nations, the nicest confusion of tongues, that has ever taken place since the days of the Tower of Babel.” To confuse things further, it is clear that, like the other inhabitants of the village, some Hawaiians took American Indian wives and raised multiethnic families (Towner 1984; Rogers 1993; Warner and Munnick 1972).

Some American Indian wives were married to and formed families with Hawaiian men and many of the American Indian wives came to the village with their American Indian slaves. Even after Great Britain’s Slavery Abolition Act of 1833, slavery persisted in the village. For example, in 1838, James Douglas wrote to Simpson and the Committee:

“I am most anxious to second your views, for suppressing the traffic of slaves, and have taken some steps towards the attainment of that object. I regret, however, that the state of feeling among the Natives of this river, precludes every prospect of the immediate extinction of slavery . . .” (Rich 1941: Appendix A).

Douglas set an escaped slave boy free who then served the Company as a free laborer.

“These proceedings, so clearly destructive of the principle of slavery, would have roused a spirit of resistance, in any people, who know the value of liberty; but I am sorry that the effect has been scarcely felt here, and I fear that all my efforts have virtually failed in rooting out the practical evil, even within the precincts of this settlement” (Rich 1941: 238).

His letter indicates that the fur trade families with slaves were very resistant to ending this particular tradition.

Because of the ethnic diversity, including the gendered ethnic diversity present in the village, combined with the lack of a documentary record written from a Hawaiian, or for that matter, any villager’s perspective, historical archeology is a critical set of methods to better understand the lives of the village inhabitants.

NPS photo.

Archeology at the Village

Excavations in Fort Vancouver Village were initiated by Louis Caywood, perhaps as early as 1947. Unfortunately, he left no field records or otherwise reported on his work there other than a short note in his 1955 final report on the fort stockade (Caywood 1955). After Caywood, there have been a variety of archeological investigations in the village, most seeking to identify house sites and elucidate the character of and differences between houses on the basis of architectural remains, including hearths, postholes, subfloor cellars, and domestic refuse left on the house floors.

In 1968 and 1969, Susan Kardas and Edward Larrabee, using a variety of hand-dug trenches and test pits combined with mechanized removal of sod, identified four house sites (Houses 1, 2, 3, and 4) and a number of extramural pits. One large concentration of rock, Kardas felt, was the foundation to a warehouse (Larrabee and Kardas 1968; Kardas 1970).

The methods of ethnic identification in historic archeology of the 1960s focused on the exploration of “ethnic markers,” like diagnostic stone tools (e.g., projectile points), and precluded careful analysis of the ways in which domestic artifacts and consumables, including foods, furnishings, and tools might reflect the ethnic identity of individuals (Lightfoot 2005a, 2005b). In this vein, Kardas (1971) attempted to infer the ethnicity of the inhabitants of the four houses on the basis of diagnostic artifacts, specifically those of Native Hawaiian and American Indian origins. Notably, she found an anthropomorphic steatite effigy pipe in House 2 that appeared to be of Polynesian design, as marks on the face resembled facial tattooing.

Most of the materials Kardas recovered, however, were British or European in origin, probably purchased from the HBC “Sale Shop,” which was the principal retail outlet for the employees of the company, early missionaries, and Oregon Trail settlers. Kardas attempted to explain the lack of ethnic markers by suggesting that Hawaiian males of the commoner class neither had the opportunity for expression of ethnic behavior, nor were they traditionally trained in artistic expression. The historical record suggests, however, that some traditional behaviors were maintained by Native Hawaiians in the fur trade, including language, spatial segregation, and traditional dances like the hula (see also Rogers [1993]).

Further confusing efforts to identify ethnic identities is the fact that some Hawaiian laborers lived in the Northwest for longer periods of service and adapted to the dominant culture. John Cox, for example, came with the Astorians in 1811 as a royal observer for King Kamehameha I, and retired at Fort Vancouver in 1843, continuing to live at the village until his death in 1850. Hawaiians serving a longer term of service or who immigrated to the Pacific Northwest may have been much different from those that were on a much shorter term (3 years being the normal contract length).

In the 1970s and early 1980s, archeologists carried out a number of cultural resource management studies associated with a revision in the Interstate 5/State Route 14 interchange (Chance and Chance 1976; Chance 1982; Carley 1982; Thomas and Hibbs 1984). The studies attempted to characterize the material culture associated with the fur trade-era Fort Vancouver Village and U.S. Army use of the site; identify and characterize important features of the village area, including the pond, hospital, village houses, U.S. Army Quartermaster’s quarters and workshop areas; and identify some of the differences between village houses to verify the historical accounts of “ethnic neighborhoods” (Bray 1984: 814-831).

Thomas and Hibbs (1984) greatly improved the description of the characteristics of village architecture and other recurring features and provided a better general understanding of the archeology of the village. Their excavations included two house sites that were directly tied to Native Hawaiians—the Kanaka house and William Kaulehelehe’s house. Both were tested, but were not subjected to more extensive excavations, so information on the sites is limited. Both sites were identified on the 1846 Covington map as being likely related to Native Hawaiian occupations (Thomas and Hibbs 1984: 312-324, 619-625). At the Kanaka House (Operation 20A, Phase 2), six 5 feet by 5 feet test units were initiated, only three of which were completely excavated. These yielded a series of posts, stakes, small pits, and a rectangular burnt footing, which appear to be part of the house. Artifacts were typical of other Fort Vancouver domestic assemblages, including ceramics dominated by transfer printed earthenware, with lusterware, banded ware, cottage ware, and stoneware also present. Vessel glass was dominated by dark olive and green bottle fragments. There were a few buttons, over 100 glass beads, some clay tobacco pipe fragments, and a variety of architectural debris including wrought and cut nails and window glass.

At the William Kaulehelehe house site, only two 5 feet by 5 feet test excavation units were excavated. Features included rectangular post molds and pits, one filled with trash. These features were inferred to be situated on the extreme eastern edge of the house. Ceramic artifacts included lusterware, transfer-printed earthenware, Chinese export porcelain, and ironstone. There were relatively few fragments of bottle glass (again dominated by dark olive and green alcohol bottles), mirror glass, buttons, beads, clay tobacco pipe fragments, a slate pencil, a tortoiseshell comb, a variety of metal tool fragments, including files and an axe blade, lead shipping seals, and mammal and bird bone. Typical architectural debris included wrought and cut nails and window glass fragments. A few fragments of chert debitage were also noted, which Thomas and Hibbs (1984:624) attribute to the ethnicity of the inhabitants, suggesting perhaps that Kaulehelehe or his Hawaiian wife, Mary Kaai, used stone tools in a traditional Hawaiian manner.

Bray’s (1984) analysis of ethnicity, using the Thomas and Hibbs excavation data, was unsuccessful in identifying specific ethnic groups for a variety of reasons. She did see some correlations, however, with European and French Canadian assemblages associated with higher frequencies of stoneware and hand painted ceramics; and dark olive and green glass (associated with alcoholic beverages); and American Indian and Hawaiian households containing more lead shot and beads. She suggested that at Fort Vancouver, the overarching homogeneity between assemblages, however, was evidence of the adaptability and flexibility of culture.

D.J. Rogers (1993) summarized the historical and archeological record for a variety of fur trade sites that employed Native Hawaiians, including the Fort Vancouver Village. Rogers felt that diagnostic Hawaiian stone artifacts that may have made the trip from Hawaii or were manufactured in the Northwest, like poi pounders, were indistinguishable from the groundstone pestles and mauls of the indigenous American Indians of the lower Columbia. Likewise, he found no evidence of diagnostic stone adzes in the Fort Vancouver archeological collections, but inferred that metal counterparts had supplanted this type of diagnostic Hawaiian artifact by the 1800s.

However, Rogers (1993:107-115) did infer that the rock feature that had been recorded by Kardas as the foundation for a warehouse was likely a Hawaiian shrine. Rock concentrations and piles built by commoners were ubiquitous in Hawaii, and served “to honor personal gods and ensure success and safety during labor.” Rogers suggested that the alignment of rocks in parallel with the riverfront, the presence of upright stones (which he inferred as pohaku), and the absence of much inorganic debris, was consistent with an interpretation that the feature was a shrine.1

In 2001-2003, NPS staff excavated within the village to collect data to identify any additional house sites present; confirm historical accounts, maps, and drawings of the site; verify the location of house sites identified by Kardas and Larrabee; and provide additional information for the development of a concept plan for the interpretation of the village. A field school systematically surveyed the site with 1.5 by 1.5 foot shovel test units in a grid pattern to relocate three of the four house sites identified by Kardas and to collect a sample of a newly identified house (House 5) found in a shovel test in 2001. Remote sensing work using ground penetrating radar, electrical resistivity, and magnetic gradiometry, among other techniques, was used to survey the village area in 2002 and 2003. The outcome of the archeological research was the identification of at least five previously unknown village houses (identified as Houses 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9).

The 2001-2003 NPS project contributed to the restoration and reconstruction of the circa 1829-1860 village landscape. As an early phase of this restoration and reconstruction project, a fence-line that delineates the eastern edge of the village was constructed in 2001. Since then, two historic roads, two houses (Houses 1 and 2), and some of the fence lines interior to the village have been reconstructed.

The Columbia River Crossing project, associated with a replacement bridge project for Interstate 5, conducted additional test excavations in 2009 within the village site on lands managed by the NPS, the U.S. Army Reserve, and the Washington Department of Transportation. NPS test excavations confirmed the location of House 4 on NPS lands and the “Kanaka House” on U.S. Army Reserve property. An additional house site was identified within U.S. Army Reserve property (the “Joseph Tayenta House”) that represents a newly identified resource.

An assemblage of artifacts similar to those found during 1980s investigations was recovered during the 2009 “Kanaka House” excavations (O’Rourke, Miles, and Wilson 2010). Notably, a Phoenix button, a type found infrequently in the Pacific Northwest and sometimes tied to the Nathaniel Wyeth expeditions of 1832 or 1833 (Strong 1960; 1975), was recovered from the site. Throughout the Fort Vancouver HBC deposits, including the village, Pacific coral has been recovered in the form of small fragments and as the constituent in mortar for chimneys and the powder magazine (Pierson, Adams, and Wilson 2009). A distinctively larger piece was recovered by Kardas at House 2.

Robert Cromwell’s research (2006), while not explicitly addressing Hawaiians, did note similarities in ceramic assemblages between households within the village, including House 2 that contained the possible Hawaiian-inspired steatite pipe and large piece of coral. Surprisingly, Miller’s index values calculated for the assemblages in the village were not much lower than those calculated for the Chief Factor’s House. Factoring in the tariff prices on HBC goods, which favored the gentlemen class, the House 2 assemblage was lower in value, but not significantly lower in value compared to other house sites in the village. Cromwell inferred that the villagers expended significant resources to acquire ceramics that reinforced the social standing of the Métis and Indian women within the fur trade culture.

Adding Landscape Studies to the Research Agenda

To date, the archeology of the village has focused on the identification of house sites using the density of mid-19th century artifacts as a primary means of discovery, with the assumption that the higher the density, the more likely that a house floor or its associated halo of sheet trash has been discovered. Archeologists have conducted large area excavations to sample selected house floors, often identified on the basis of features like hearths, cellars, and patterns of post holes. While this has been useful in defining spatially-distinct house sites, there are significant gaps in the archeological data for the village that could preclude effective interpretation of the lives of its inhabitants, including Hawaiians. Because much of the focus has been placed on the houses, there is relatively less known about the activity areas and gardens that were present within the village.

Test excavations in 2005-2007 within the John McLoughlin/Fort Vancouver formal garden verified the efficacy of methods for more broad-scale exploration of the fort’s surrounding landscape using pollen, phytolith, and macrobotanical analyses. There is a dearth of information on outbuildings within the village, including privies, barns, animal sheds, and shops. Related to this, how did the inhabitants of the village use the spaces around the more obvious dwellings, and is there evidence for outlying activity areas, outbuildings, including privies, and other remains of the village landscape?

Examination of the sketch attributed to George Gibbs in 1851 suggests that certain houses had attached fenced areas. It is likely that the landscape around houses supported important economic pursuits conducted outside of work hours. Does the presence of outbuildings, gardens, and other activity areas within the spaces around buildings reflect household economic specialization, some of which could be tied to ethnicity? Likewise, specific sites could be associated with cultural affiliation and religious beliefs, like those hypothesized by Rogers (1993).

In the summer of 2010, I began to explore these questions with the joint NPS, Portland State University and Washington State University public archeological field school, employing landscape archeology techniques. Test excavations around two of the hypothesized garden areas yielded a number of extramural pits, hearths, and postholes. The artifacts and samples are still being analyzed and there is another year, at least, of field work. The results to date demonstrate the utility of landscape techniques to address an important source of data for issues of identity and ethnicity, including the lives of Hawaiians at Fort Vancouver.

Archeological Contributions to Park Interpretation

Why should we care about the Hawaiians or working class ethnic diversity at a HBC fur trading post in the Pacific Northwest? Studies of identity in the colonial context, like that conducted by Burley (1989, 2000), Cusick (2000), Lightfoot (2005a), Silliman (2010), Voss (2008) and others have explored the variety of strategies by which indigenous and non-indigenous groups interacted and borrowed, creolized, and otherwise mixed elements of material culture into their daily lives. The evidence to date suggests that there are more similarities than differences between village households, regardless of ethnicity or household makeup. More fine-grained, material-specific analyses may be able to better tease out differences between households, and landscape use. This work is important because it contextualizes people who were critical to the fur trade era but whose history is not well recorded.

Currently, a number of students are working on or completing research on excavations within the village, including Delight Stone’s dissertation which explores gender (Stone 2011), Meredith Mullaley’s thesis on architecture (Mullaley 2011), Dana Holschuh’s research on ceramics, Katie Wynia’s study on tobacco consumption, and Stephanie Simmons’s research comparing reuse of glass bottles in the village with nearby contact-period Chinook village sites. These studies refine our picture of individuals at HBC’s Fort Vancouver.

Beyond the purely academic interest in colonial contact, one value of scientific exploration of the village is in its ability to engage people in the history of Hawaiians and the other diverse people of the fur trade. The village is a unique archeological landscape that provides, in a modern and easily accessible urban environment, opportunities to explain how historical archeology recovers evidence of the lives of an early colonial population. Public research and interpretive programs provide urban and non-traditional park users a link to stories and intellectual inquiry that tie the context of the workers’ village to meaningful lessons in history. Recent Fort Vancouver park programs to engage youth help to integrate the public archeology program into an overnight and day program for disadvantaged and non-traditional youth from the metropolitan area. This brings non-traditional consumers of history into direct contact with the scientific role of historical archeology in recovering the lives of people who are poorly represented in history.

Another important program is being designed by Brett Oppeggard, who (with Washington State University, Vancouver, and the University of Texas) is developing a mobile storytelling product (http://fortvancouvermobilesubrosa.blogspot.com/). The first element of the project, designed for mobile devices, focuses on the Hawaiian story at the village. The project includes filming of Hawaiian actors in period dress performing a hula. Through these and other means, the local Hawaiian community and other communities will be given greater access to, and hopefully become more deeply engaged in, the history and the preservation of the village. The research we are generating will better shed light on how Hawaiians lived and adapted to the fur trade at Fort Vancouver and the Pacific Northwest, while bringing that unique adaptation to a public audience.

1 After this paper was prepared, portions of this feature were re-excavated by NPS archeologists in the summer of 2011. These excavations determined that most of the feature had been disturbed by the 1969 excavations. Exposure of an intact portion of the feature clearly showed that the rocks were not of cultural origin, and likely represents a natural accumulation of rock on the northern margin (inlet) of a pond connecting to the Columbia River.

Notes

Prepared for the Symposium “Kanaka”: Native Hawaiians on the American Frontier, Chair and Organizer Chelsea E. Rose, Society for Historical Archeology’s Conference on Historical and Underwater Archeology, Austin, Texas, January 5-9, 2011.

By Douglas C. Wilson, NPS and Portland State University

References

Beechert, Edward and Alice Beechert

2005 Hawaiians..

Bray, Tamara

1984 Ethnic Differences in the Archaeological Assemblages at Kanaka Village. Appendix C in Thomas, Bryn, Charles Hibbs, Jr., and others, Report of Investigations of Excavations at Kanaka Village/Vancouver Barracks, Washington, 1980/1981. Report to Washington State Department of Transportation, Olympia, Washington.

Burley, David V.

1989 Function, Meaning and Context: Ambiguities in Ceramic Use by the Hivernant Metis of the Northwestern Plains.Historical Archaeology 23(1): 97-106.

Carley, Caroline D.

1982 HBC Kanaka Village/Vancouver Barracks, 1977. University of Washington, Reports in Highway Archaeology, No. 8.Seattle, Washington.

Caywood, Louis R.

1955 Final Report, Fort Vancouver Excavations. Manuscript on file, NPS, San Francisco, California.

Chance, David H. and Jennifer V. Chance

1976 Kanaka Village/Vancouver Barracks, 1974. University of Washington, Reports in Highway Archaeology, No. 3. Seattle, Washington.

Chance, David H. (editor)

1982 Kanaka Vi11age/Vancouver Barracks 1975. University of Washington, Reports in Highway Archaeology, No. 7. Seattle, Washington.

Cromwell, Robert John

2006 “Where Ornament and Function are so Agreeably Combined”: Consumer Choice Studies of English Ceramic Wares at Hudson’s Bay Company Fort Vancouver. Doctoral dissertation, Department of Anthropology, Syracuse University, Syracuse, New York.

Cusick, James G.

2000 Creolization and the Borderlands. Historical Archaeology 34(3): 46-55.

Erigero, Patricia C.

1992 Cultural Landscape Report: Fort Vancouver National Historic Site, Volume II. Patricia Erigero, Consultants. Report prepared for the Cultural Resources Division, Pacific Northwest Region, NPS, Seattle, Washington.

Hussey, John A.

1957 The History of Fort Vancouver and its Physical Structure. Report on file at Fort Vancouver National Historic Site, Vancouver, Washington.

1976 Fort Vancouver National Historic Site, Historic Structure Report, Historical Data, Volume II. Manuscript on file, Fort Vancouver National Historic Site, Vancouver, Washington.

Kane, Paul

1859 Wanderings of an Artist Among the Indians of North America: From Canada to Vancouver’s Island and Oregon Through the Hudson’s Bay Company’s Territory and Back Again. Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans, and Roberts, London.

Kardas, Susan

1970 1969 Excavations at the Kanaka Village Site, Fort Vancouver, Washington. Report to National Park Service, San Francisco from Bryn Mawr College, Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania.

1971 "The People Bought This and the Clatsop Became Rich," a View of Nineteenth Century Fur Trade Relationships on the Lower Columbia between Chinookan Speakers, Whites, and Kanakas. Doctoral dissertation, Bryn Mawr College, Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania.

Kauanui, J. Khaulani

2007 Diasporic Deracination and “Off-Island” Hawaiians.The Contemporary Pacific 19(1): 138-160.

Klimko, Olga

2004 Fur Trade Archaeology in Western Canada: Who is Digging up the Forts? In The Archaeology of Contact in Settler Societies, Edited by Tim Murray, pp. 157-175. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Larrabee, Edward, and Susan Kardas

1968 Exploratory Excavations for the Kanaka Village, Ft. Vancouver National Historic Site. Report to the NPS, Fort Vancouver National Historic Site, Vancouver, Washington.

Lightfoot, Kent G.

2005a Indians, Missionaries, and Merchants: the Legacy of Colonial Encounters on the California Frontiers. University of California Press, Berkeley, California.

2005b Mission, Gold, Furs, and Manifest Destiny: Rethinking an Archaeology of Colonialism for Western North America. In Historical Archaeology, Martin Hall and Stephen Silliman, editors, pp. 272-292. Blackwell Studies in Global Archaeology.

Mullaley, Meredith J.

2011 Rebuilding the Architectural History of the Fort Vancouver Village. Master’s thesis, Department of Anthropology, Portland State University, Portland, Oregon.

O’Rourke, Leslie M., Todd A. Miles, and Douglas C. Wilson

2010 Results of National Park Service Archaeological Evaluations and Testing on the Vancouver National Historic Reserve for the Columbia River Crossing Project.Northwest Cultural Resources Institute Report No. 8. Fort Vancouver National Historic Site, Vancouver, Washington.

Pierson, Heidi K., Martin E. Adams, and Douglas C. Wilson

2009 Fort Vancouver Powder Magazine Archaeology 2004.Northwest Cultural Resources Institute Report No. 7. Fort Vancouver National Historic Site, Vancouver, Washington.

Philips, Lisa

2008 Transitional Identities: Negotiating Social Transitions in the Pacific NW 1825-1860s. The Canadian Political Science Review 2(2):21-40.

Rich, E. E.

1941 The letters of John McLoughlin, from Fort Vancouver to the Governor and Committee; First Series, 1825-38. Champlain Society, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Rogers, D. J.

1993 Ku on the Columbia: Hawaiian Laborers in the Pacific Northwest Fur Industry. Master's thesis, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon.

Silliman, Stephan

2010 Indigenous Traces in Colonial Spaces: Archaeologies of Ambiguity, Origin, and Practice. Journal of Social Archaeology 10: 28-58.

Simpson, Sir George

1847 An Overland Journey Round the World During the Years 1841 and 1842. Lea and Blanchard, Publishers, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Stone, Delight

2011 Culture Contact and Gender in the Hudson’s Bay Company of the Lower Columbia River 1824-1860. Doctoral dissertation, School of Archaeology and Ancient History, University of Leicester.

Strong, Emory

1960 Phoenix Buttons. American Antiquity 25(3):418-419.

1975 The Enigma of the Phoenix Button.Historical Archaeology 9:74-80.

Towner, Ron

1984 Demographics of Kanaka Village 1827-1843. Appendix B in Thomas, Bryn, Charles Hibbs, Jr., and others, Report of Investigations of Excavations at Kanaka Village/Vancouver Barracks, Washington, 1980/1981. Report to Washington State Department of Transportation, Olympia, Washington.

Thomas, Bryn, Charles Hibbs, Jr., and others

1984 Report of Investigations of Excavations at Kanaka Village/Vancouver Barracks, Washington, 1980/1981. Report to Washington State Department of Transportation, Olympia, Washington.

Voss, Barbara L

2008 The Archaeology of Ethnogenesis: Race and Sexuality in Colonial San Francisco. University of California Press, Berkeley.

Warner, Mikell De Lores Wormell, and Harriet Duncan Munnick

1972 Catholic Church records of the Pacific Northwest: Vancouver, Volumes I and II, and Stellamaris Mission. French Prairie Press: Saint Paul, Oregon

Wilson, Douglas C., and Theresa E. Langford, Editors

2011 Exploring Fort Vancouver. University of Washington Press, Seattle, Washington.