Archives of Ontario, F 596

On November 8, 1861, the USS San Jacinto stopped the RMS Trent, a British mail packet, and the Union captain removed Confederate diplomats James Mason and John Slidell. In the minds of Canadians, the Trent Affair triggered sinister memories of border disputes and military invasions from the south. Just before Christmas in 1861, a London Times correspondent in Montreal reported that Canada did not intend to stand by waiting for the United States to strike again. “Armed to the teeth,” Canada intended to field “fully 60,000 men in arms to resist the invasion of her soil.”

President Abraham Lincoln saw the pitfalls inherent in the Trent Affair. “We must,” he said, “stick to American principles concerning the rights of neutrals.” By New Year’s Day, diplomacy resolved the crisis and freed Mason and Slidell. “A feeling of relief as from some impending evil at once came over the people [of Canada].”

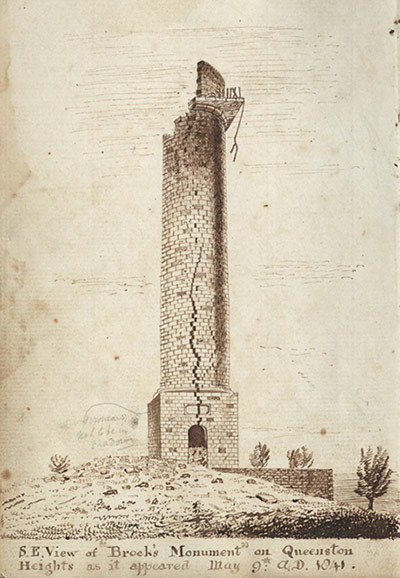

But the incident animated old fears. Once again, tensions between the United States and Canada/Great Britain bubbled and nearly boiled. In 1838, the Aroostook “War” stemmed from a dispute over the border with Maine. Oregon’s border became a national issue in US politics in the 1840s. For decades, anti-British agitators crossed between the United States and Canada—in 1840, terrorists exploded a bomb damaging the monument of Sir Isaac Brock. And in the 1860s and 1870s, members of the Fenian Brotherhood in the United States staged raids into Canada, hoping to pressure Britain to leave Ireland.

A peaceful border, it seems, requires decades of work.

Last updated: October 23, 2021