Part of a series of articles titled Coastal Geomorphology—Storm Types.

Previous: Tropical Storms

Next: El Niño and La Niña

Article

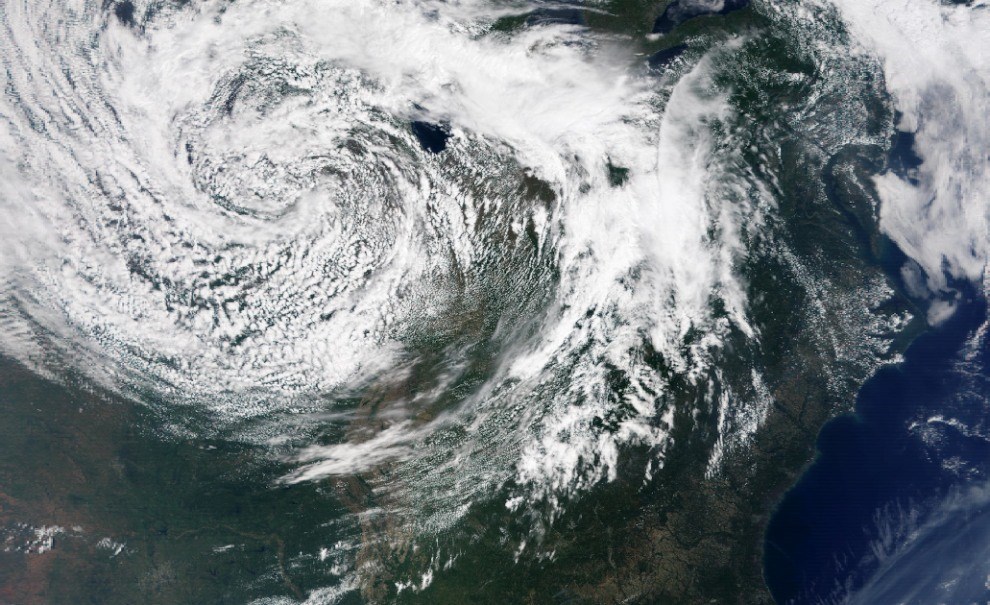

NASA image.

Known by many names, extratropical storms form outside of the tropics, usually at mid-latitudes between 30° and 60° latitude from the equator. The names of these storms typically reflect local conditions, often indicating the origin of a storm’s prevailing winds (e.g., “northeasters”/“nor’easter” or “southwesters”/“so’wester”). Extratropical storms are driven by temperature differences where two air masses meet and create a “front.” These storms are the primary drivers of coastal change along the northeast and mid-Atlantic coasts, affecting Cape Cod (Massachusetts), Assateague Island (Maryland), and Canaveral (Florida) national seashores, and Acadia National Park (Maine). They also affect inland areas of the mid-latitudes such as the Great Lakes region, including Indiana Dunes (Indiana), Sleeping Bear Dunes (Michigan), and Pictured Rocks (Michigan) national lakeshores, and Isle Royale National Park (Michigan).

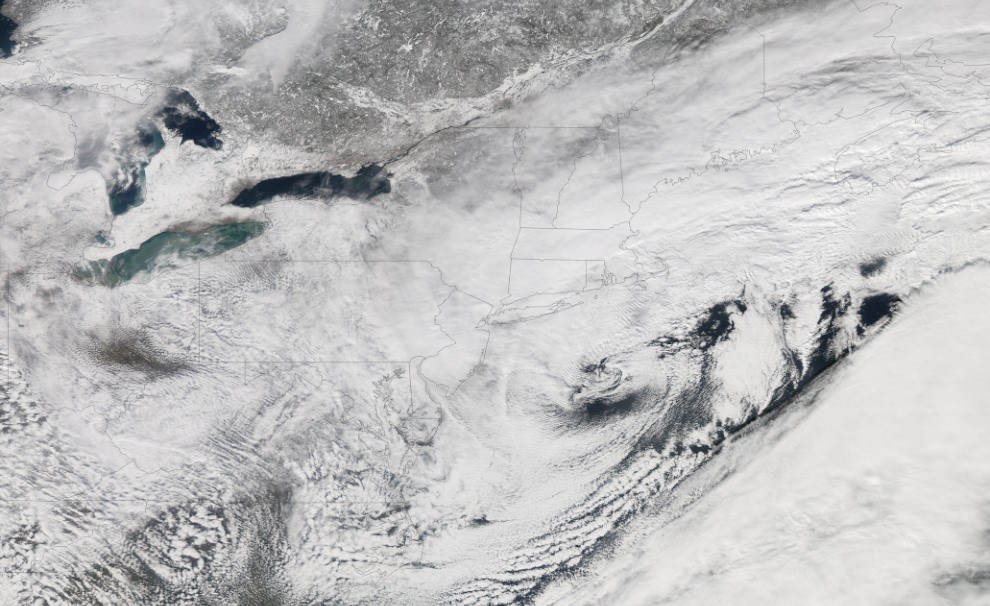

NASA image.

Extratropical cyclones can bring mild weather with a little rain and surface winds of 10–20 miles per hour (15–30 kph), or they can be cold and dangerous with torrential rain and winds exceeding 74 miles per hour (119 kph). Shorelines along the northern and mid-Atlantic coast can experience more than 20 extratropical storms every year. These winter weather events are notorious for producing heavy snow, rain, and oversized waves that crash onto Atlantic beaches, often causing beach erosion and structural damage. Wind gusts associated with these storms can exceed hurricane force in intensity. Often before a beach can recover from an extratropical storm event, another one will hit.

Part of a series of articles titled Coastal Geomorphology—Storm Types.

Previous: Tropical Storms

Next: El Niño and La Niña

Last updated: June 4, 2019